Criseo 2017 - it is ready!

Our wine Criseo Bolgheri DOC Bianco 2017 is ready.

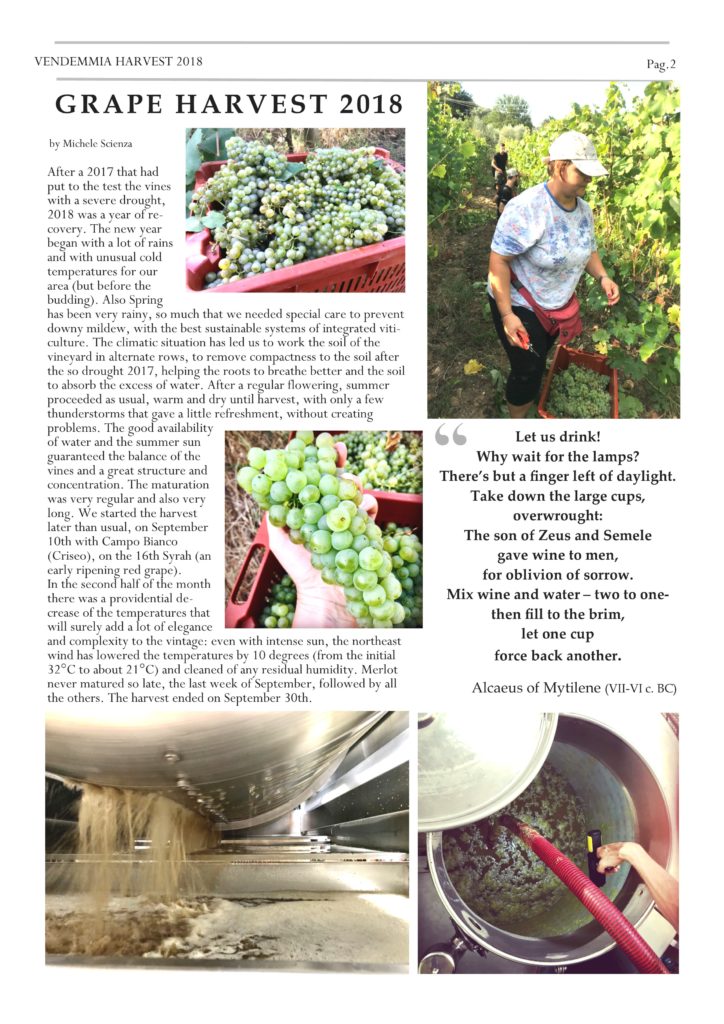

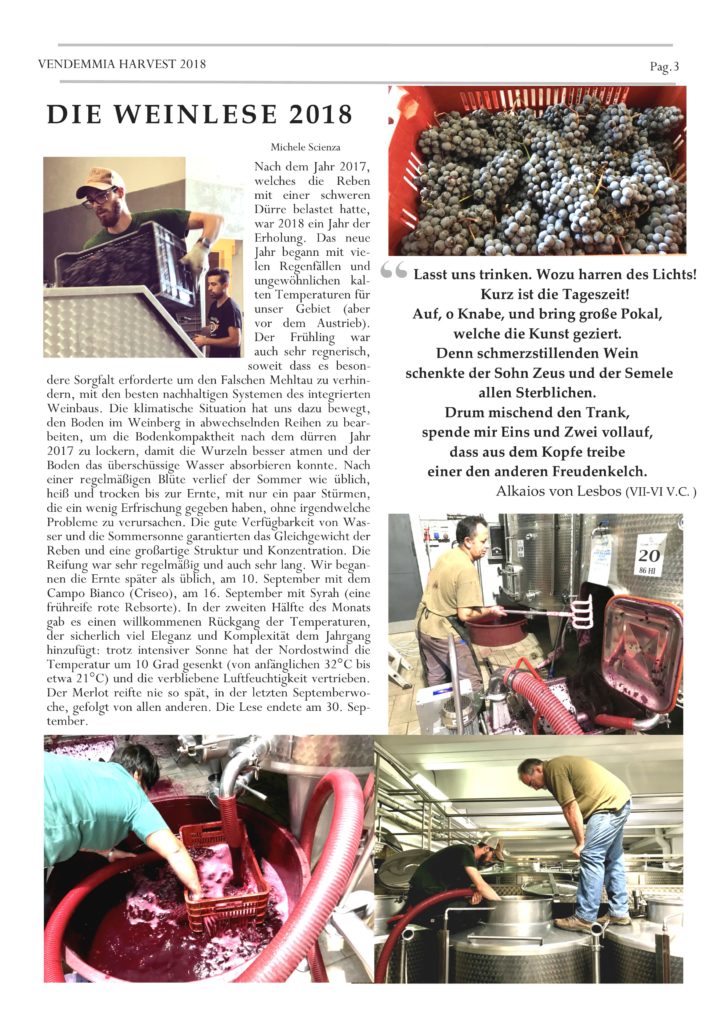

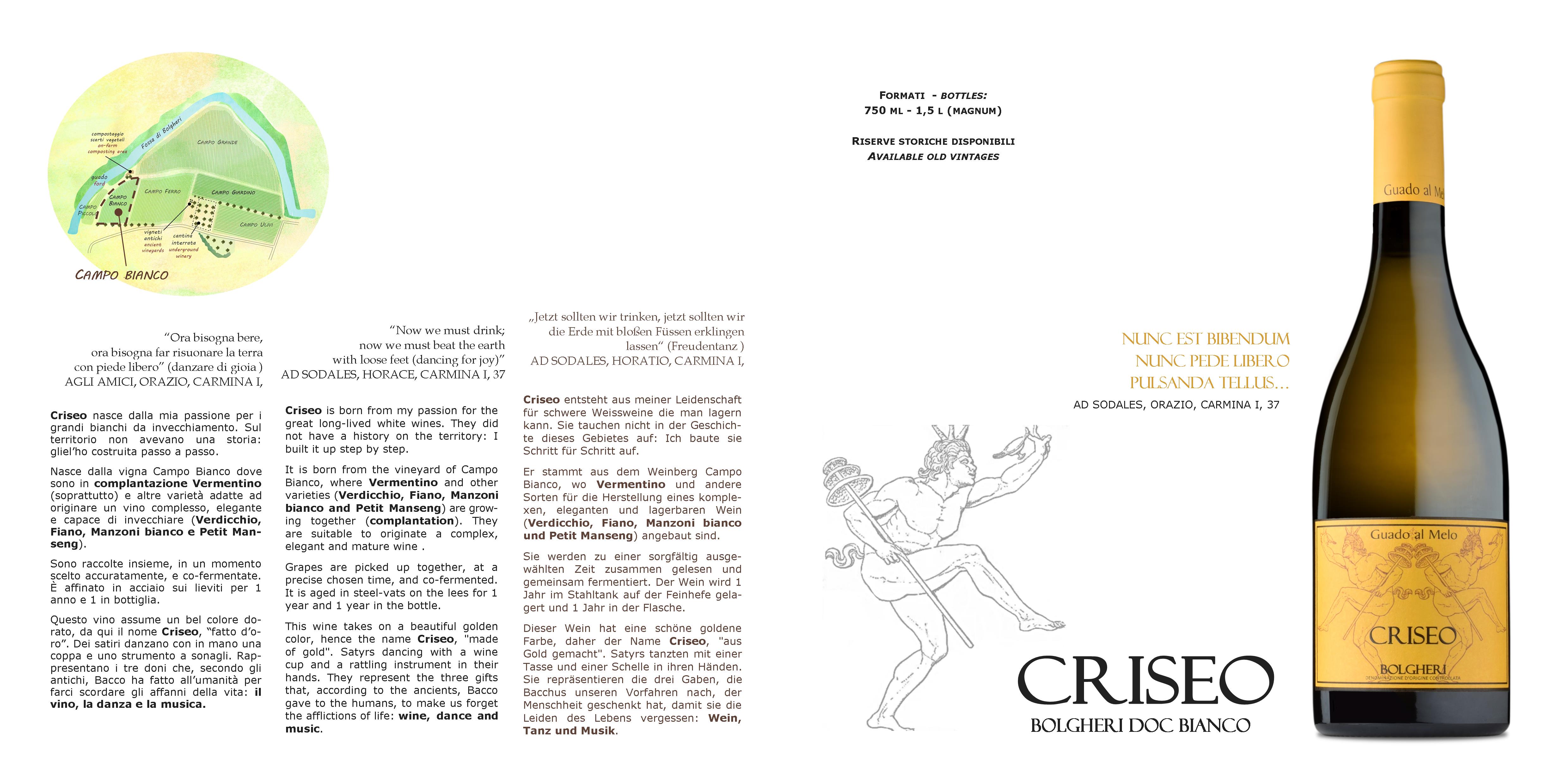

The vintage 2017 has been very dry, with big drops in production. The wines are well concentrated but very balanced. A lot of work has been done in selection to eliminate withered berries. In fact, the Criseo has a great freshness that perfectly balances the full and enveloping body, almost "fat", and very long. The color is light golden. The set of aromas is incredible: it changes over and over again. We left the glasses to the side, returning to smell them from time to time and ... each time different scents came. We have smelled aromas of tropical fruit (especially pineapple), apricot, candied fruit, orange jam, honey, yeast, saffron, broom, chamomile, mineral notes (flint and kerosene), cedar, lemon leaves ...

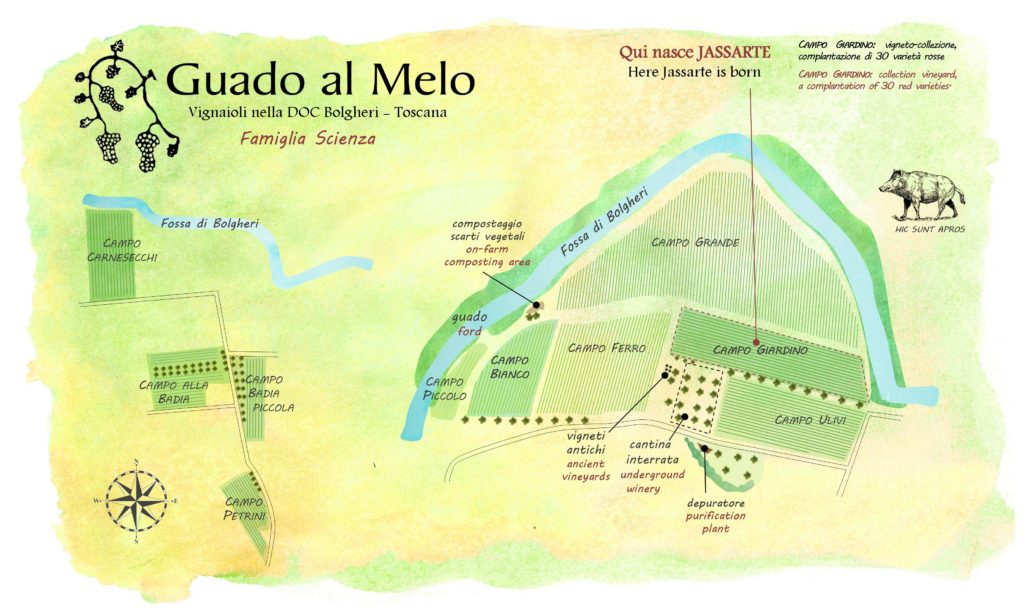

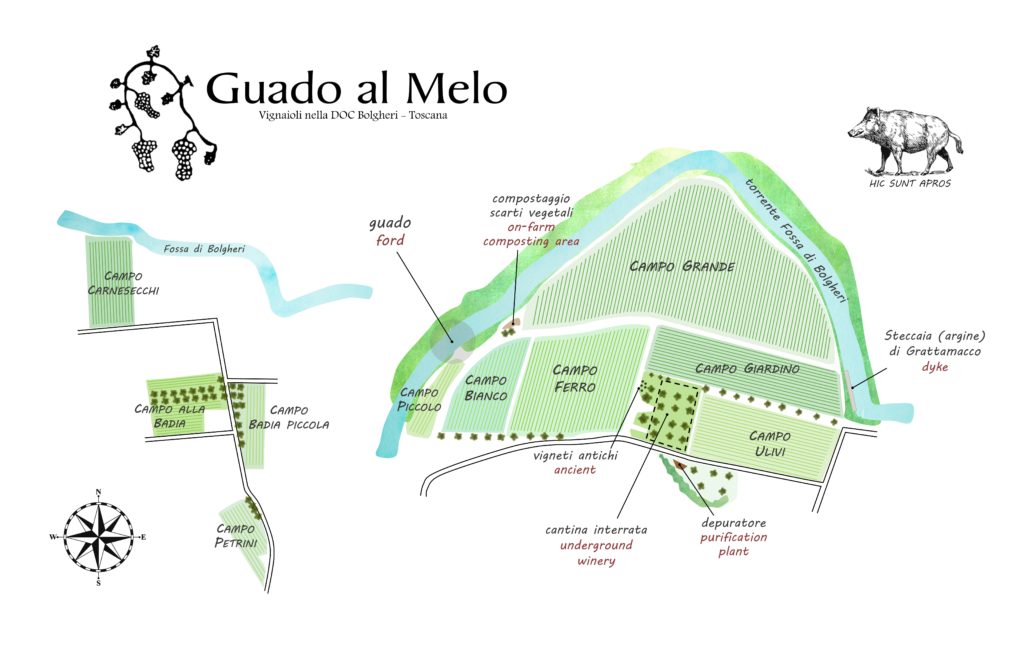

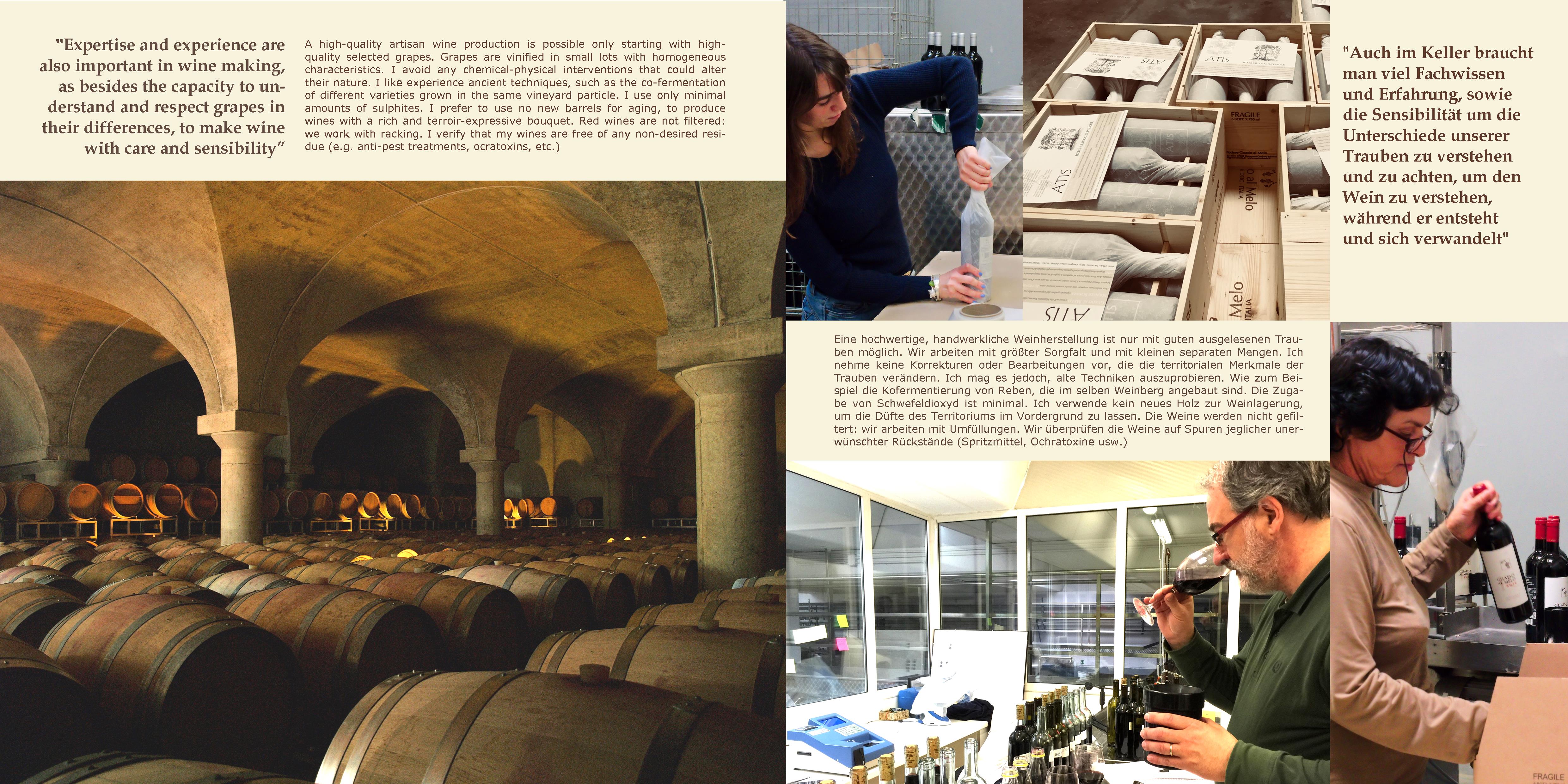

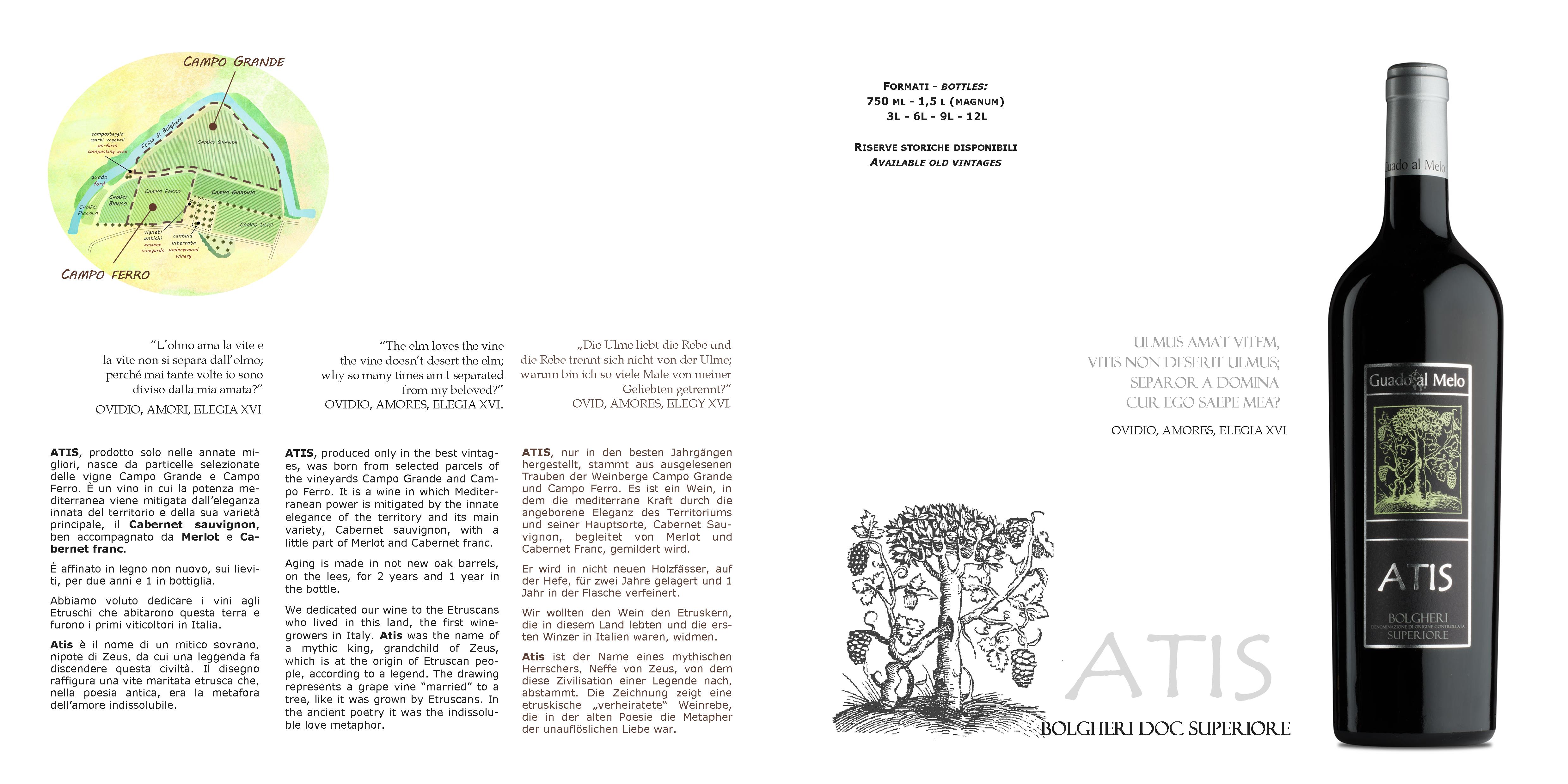

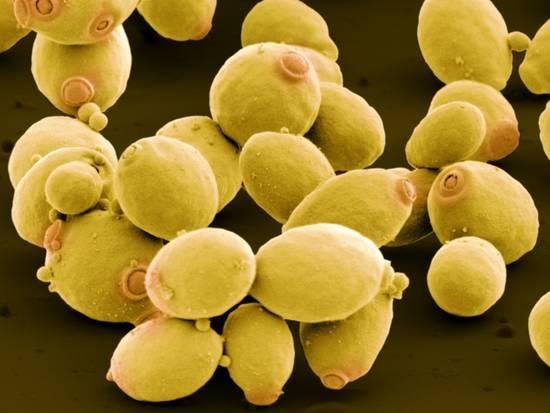

We are talking about a craft wine, that it was born from a single vineyard (Campo Bianco 0,7 ectares, naear to the ford, the "guado"), a field blend of different varieties: mostly Vermentino, and Verdicchio, Fiano, Petit manseng, Manzoni bianco. They are picked up all togheter, co-fermented and then aged on the lees for 1 year (not wood, in a steel tank), and 1 year again in bottle.

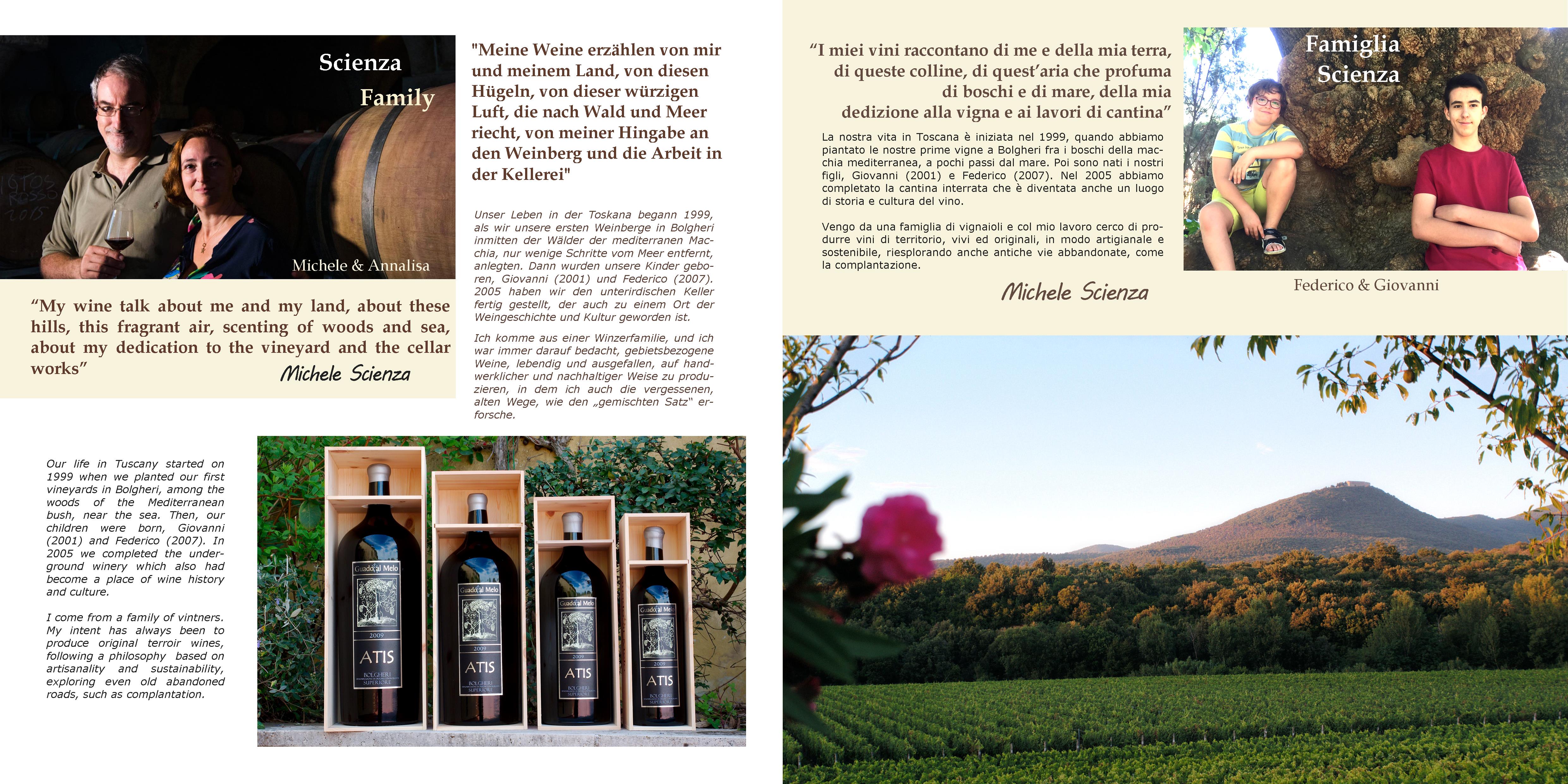

Behind all this is the work of Michele Scienza, a winemaker who fully gathers the legacy of his family.

Taste and enjoy it !

Happy Easter: we are open

We are open on Saturday, Monday and on April 25 (they are Italian public holidays), h 10-13 15-18.

We are waiting for you!

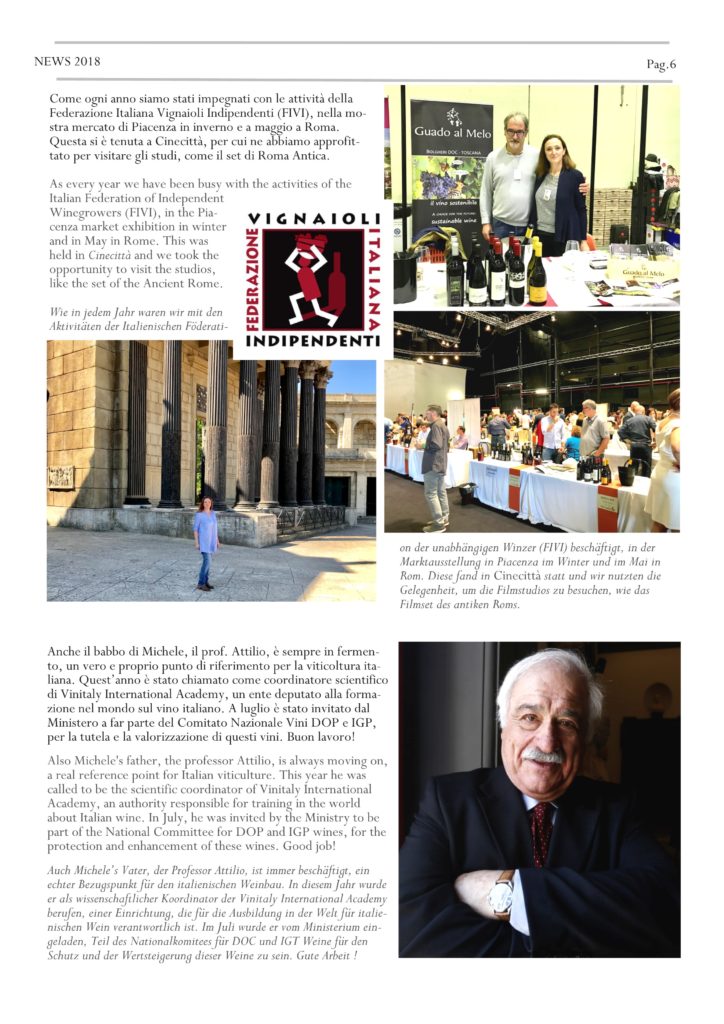

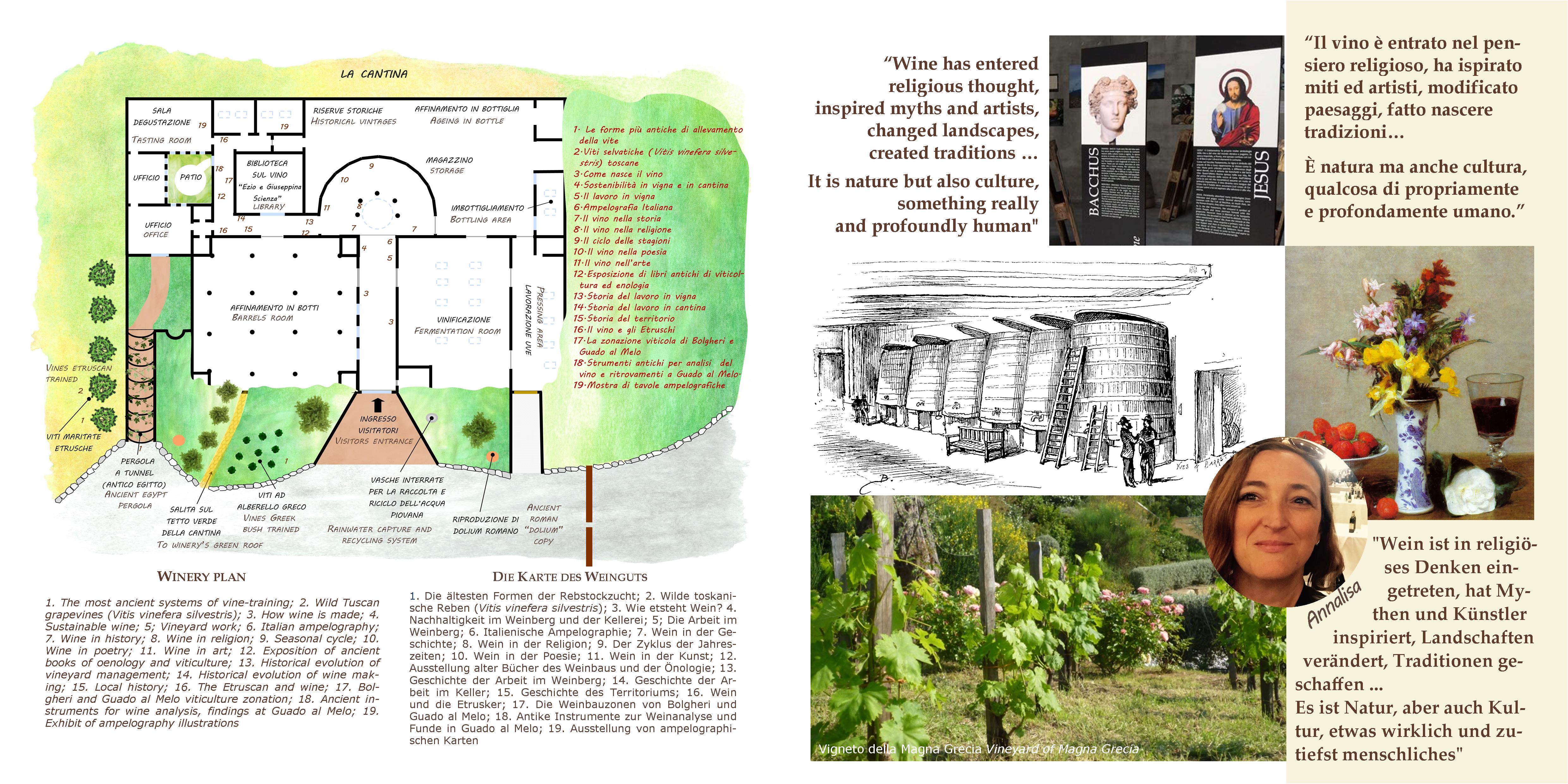

Guado al Melo is "Quality Made"

Quality Made is a high quality Cultural Identity brand that certifies companies whose activities are based on principles of cultural, environmental and social sustainability.

Quality Made is aimed at travellers looking for genuine and unique places, a travel experience that is environmentally-friendly and respectful of local communities.

Quality Made-certified companies are united by deep roots in their local territory, attention to the peculiarities of the local culture, special care in the creation of high quality products and services and their strong artisan and territorial connotation.

Founded in 2018, the brand operates in France and Italy and covers an initial group of 75 companies.

Vinitaly 2019

We'll be at Hall 7 Stand B5, c/o our italian distributor Cuzziol GrandiVini.

See you

Annalisa and Michele Scienza

April 7th-10th: Vinitaly

April 7th-10th: Vinitaly in Verona, we will be in Hall 7 Stand B5, at our distributor for Italy Cuzziol GrandiVini. We will be both Michele and me, Annalisa.

March 24th-25th: Vinissima, Tamborini Vini tasting event, our importer in Switzerland

March 24th-25th: Vinissima, Tamborini Vini tasting event, our importer in Switzerland. There will be Michele. Tamborini Vini is in Lamone, via Serta 18. Tel. +41 919357545 www.tamborinivini.ch info@tamborinivini.ch

March 17th-19th: ProWein in Duesseldorf

March 17th-19th: ProWein in Duesseldorf: we will be in Hall 16 - J25, at the stand of our importer for Germany, Consiglio Vini.

New vintages, tasting notes

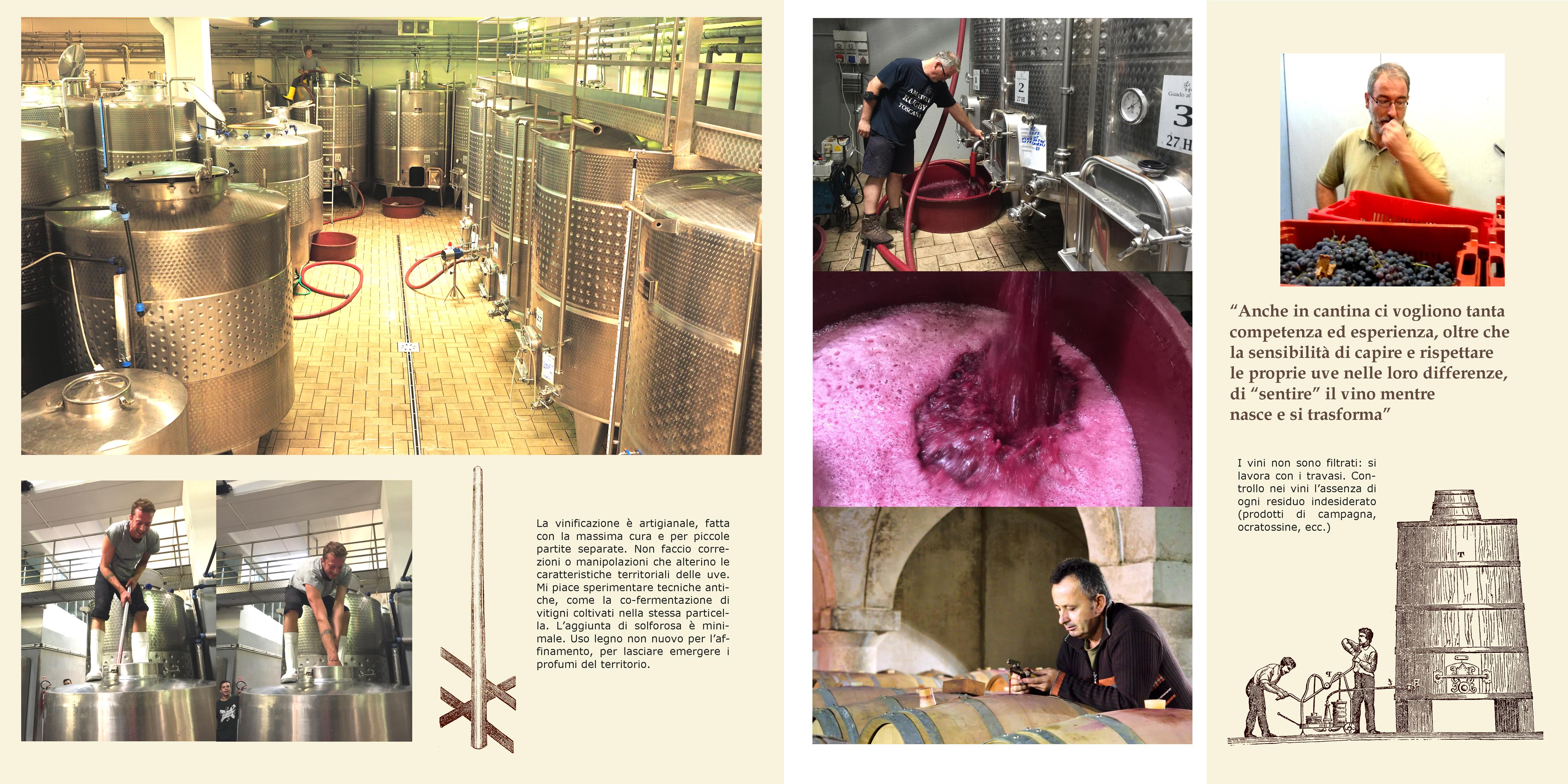

Yesterday there was a tasting among us (Michele, Annalisa, Katrin and Jadranka) of the new vintages that have just come out or are coming out. The ensemble has thrilled us: the latest years have been very positive in terms of climate. This, combined with the advanced age of the vines and the accumulated experience, has given rise to wines of great depth and interest.

We started with the youngest, L'Airone 2018, son of a very good vintage, even if the vines still had to recover after the drought of 2017 (in fact there has been a delay in development and harvest, that can not be explained otherwise) . The color is very light and bright yellow, as expected by Vermentino. The aromas are very pleasant, they remind aromas of sweet fruits and flowers, balanced and made intriguing by the bitter note (but very pleasant) of grapefruit (that distinguishes this grape variety). We have smelled the grapefruit, tropical fruits (mango, papaya, passion fruit), pear, acacia, linden. In the mouth it is very fresh, quite full-bodied and long. With this vintage we changed the bottle and then adapted the label. The result seems to me very elegant.

We also tasted the Criseo Bolgheri DOC Bianco 2017, even if it is still aging in bottle until the end of spring (more or less). There is still on sale the fantastic 2016. The vintage has been very dry, with big drops in production. The wines are well concentrated but very balanced. A lot of work has been done in selection to eliminate withered berries. In fact, the Criseo has a great freshness that perfectly balances the full and enveloping body, almost "fat", and very long. The color is light golden. The set of aromas is incredible: it changes over and over again. We left the glasses to the side, returning to smell them from time to time and ... each time different scents came. We have smelled aromas of tropical fruit (especially pineapple), apricot, candied fruit, orange jam, honey, yeast, saffron, broom, chamomile, mineral notes (kerosene), cedar, lemon leaves ... Who knows how it will change again in these last months of bottle.

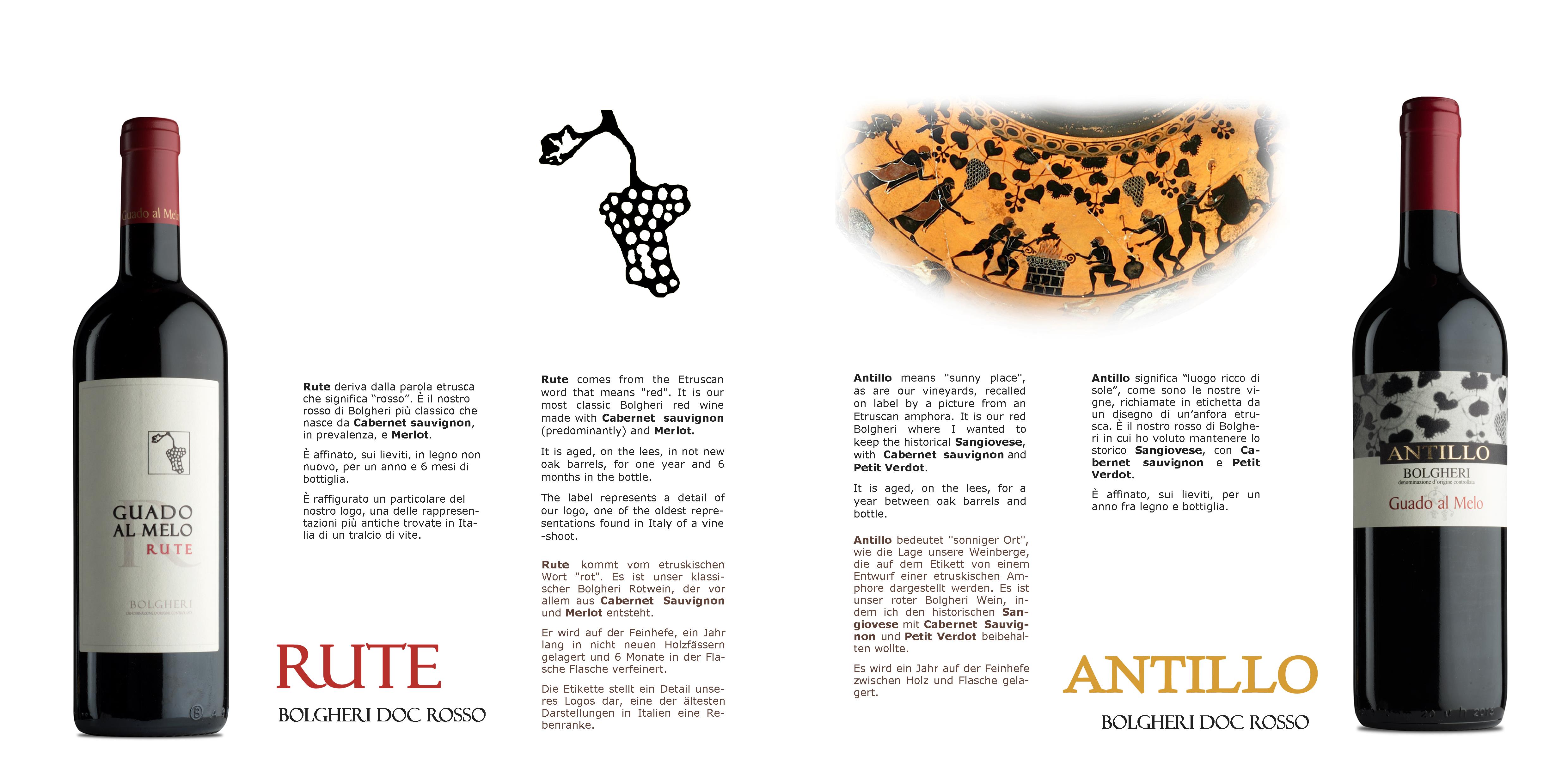

The first red is Bacchus in Tuscany 2017. In the mouth it is soft, very pleasant, with aromas dominated by the fruit (blueberry, blackcurrant and blackberry) and a pungent note (black pepper). Antillo Bolgheri DOC Rosso 2017 has a greater complexity, with more structure and freshness. The aromas reminded us of the currant (halfway between a fruit and vegetal notes), other berries, but also intense notes of Mediterranean scrub, especially of laurel and myrtle.

The Rute Bolgheri DOC Rosso 2016 is what has most surprised us. It is very vertical, although quite soft and well structured. The aromatic complexity here grows considerably, with sweet fruit bases (especially the strawberry), accompanied by the freshness of mint and intense notes of licorice and sweet tobacco. This year there will also be the Magnum format (1.5 liters). You will also have noticed the small change in the label, which gives more emphasis to the name of the wine.

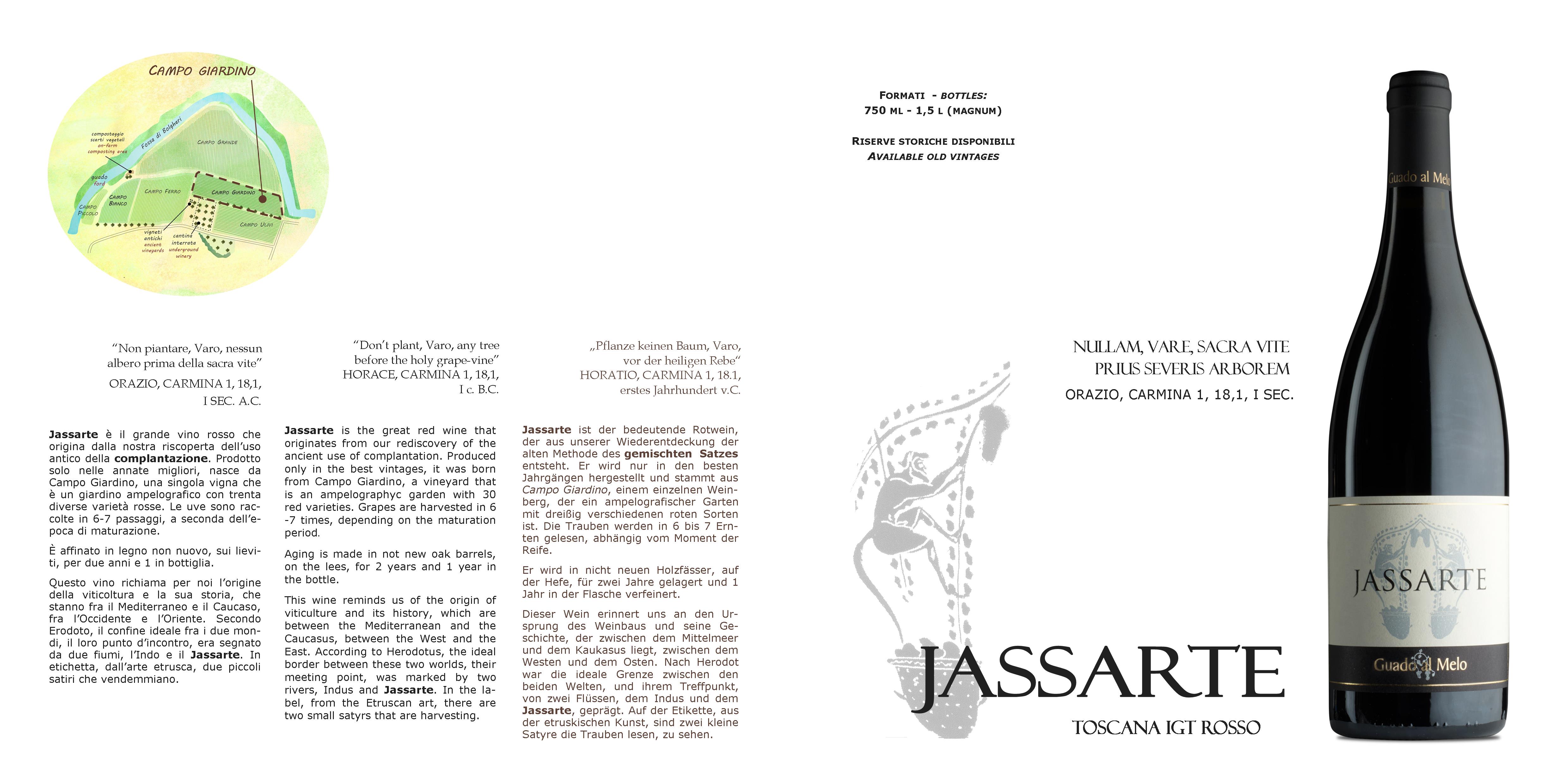

The Jassarte 2015 is instead an endless crescendo. The color stands out on the other wines due to its almost dark intensity (the others, due to the varieties, are on elegant ruby). On the nose you do not ever end up feeling aromas that change and alternate: black cherry, purple plum, its classic balsamic note of eucalyptus, a lot of spice (cloves and cinnamon), laurel, rosemary ... The body is very full, elegant, with a fresh and polished tannin. The ending is very long.

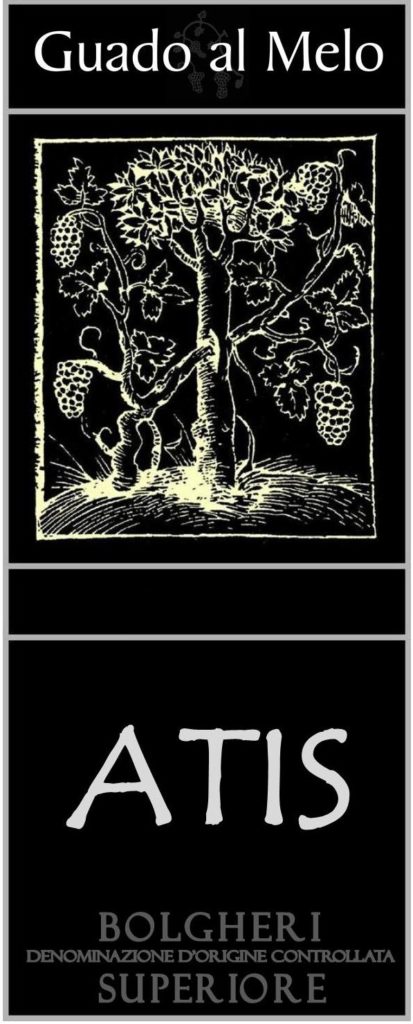

Finally, the Atis 2015, our Bolgheri Superiore, needed more bottles of Jassarte and in fact comes out shortly (while the Jassarte is already on sale for almost a month). But the wait was not in vain and it's very satisfying. As always, it has a very different soul from Jassarte, even if it shares its vintage and are "neighbors of vineyard". Here the color is intense ruby. The nose is very multifaceted, with sophisticated aromas of black fruits (blueberry, blackberry), currants, gooseberries, tomato leaves, licorice, aniseed, sweet tobacco and a note of "smoked". In the mouth it is of great character and balance, rich of freshness, with very long but not aggressive tannins. It has an incredible persistence.

However, this kind of wine is not still, it is alive and will evolve again. The same is for the other wines, especially for Criseo and Jassarte. For this reason I do not like to put the aromatic description in the data sheets (which you will find updated in the appropriate section of our website).

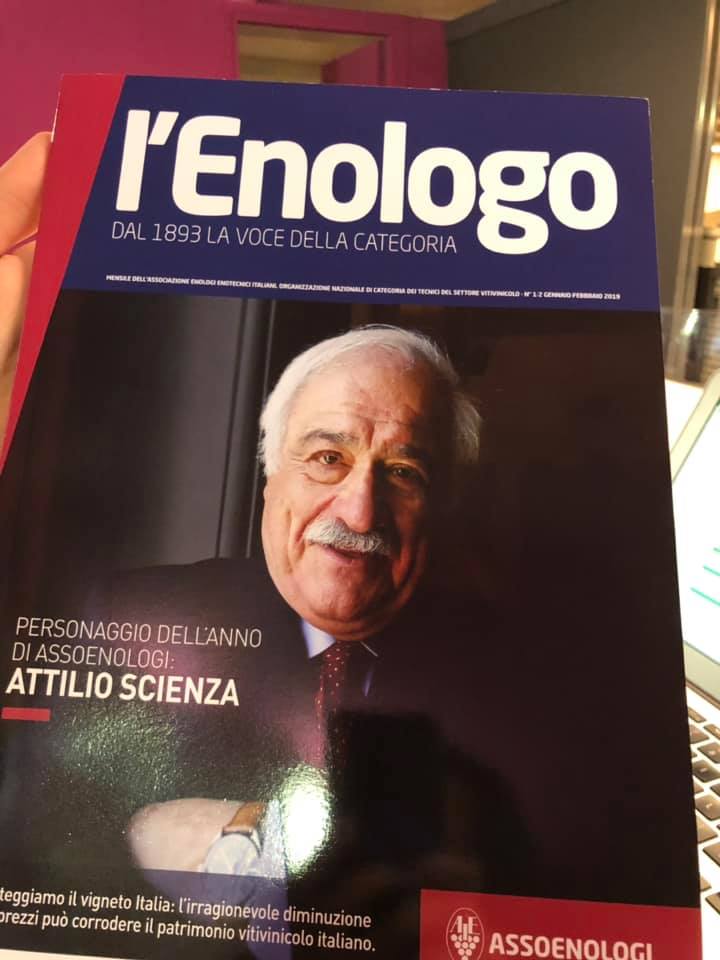

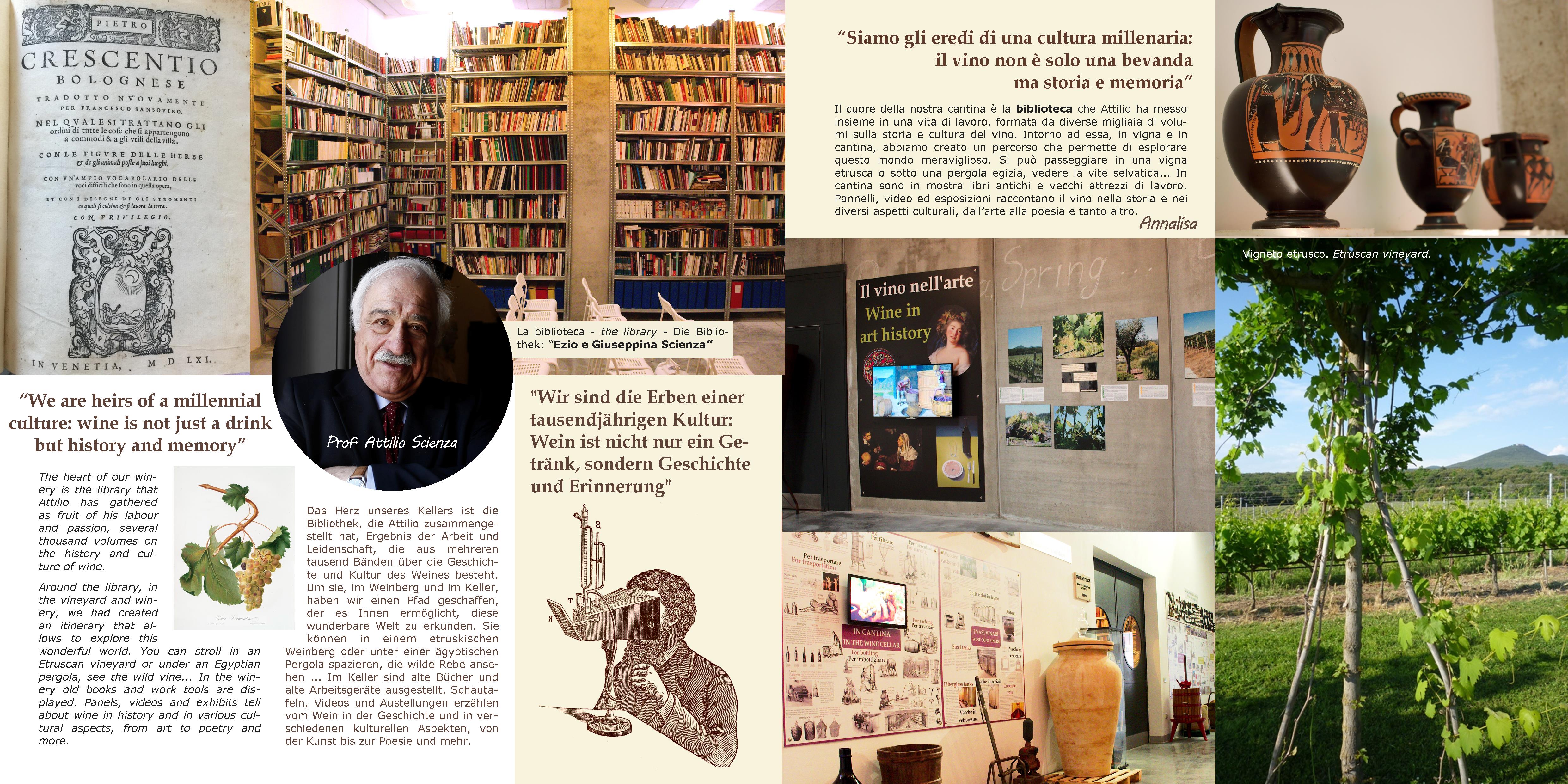

Attilio Scienza, men of the year for Assoenologi

Prof. Attilio Scienza, Michele's father, well-know expert and professor of viticulture at Milan University, is men of the year 2019 for Assoenologi, the Italian association of oenologists.

New vintage release: Jassarte 2015

After a long wait, the new vintage of our great wine Jassarte, a very complex field-blend from our Campo Giardino vineyard, is finally ready. 2015 was a very interesting vintage of great balance, which "consoled us" from a difficult 2014, in which we decided that there was not enough quality for a wine of this level.

On the other hand, 2015 gave us a great wine. It have an intense color, very deep. The aromas are complex and changing, but especially cherry, cardamom, incense, tobacco and chocolate stand out. In the mouth it is very velvety and full, even if well balanced, of considerable length.

You just have to taste it!

Here is the technical sheet, for those interested.

Season's Greetings

Saremo chiusi per ferie dal 22/12/18 al 06/01/19 compresi.

We’ll be on holiday from 22/12/18 to 06/01/19.

Wine and the Etruscan IV: the wine into the social life and religion.

“They live in a region that produces everything and, by engaging in work, have fruits with which they can not only eat enough, but also enjoy a life of pleasure and luxury.” Diodorus Siculus (I c. B. C.).

About Etruscan wines:

We have no direct Etruscan written references to their wine; our knowledge comes only through Roman sources. For example, Martial and Horace praised the Massico (from the Etrurian Campania) but they scorned the rosé from Veio. One should not take these negative judgments too seriously, however, since they appear at the historical juncture when the Etruscans were in serious decline, already under the heel of the Roman Empire. Later, Columella wrote, in his 1st-century De re rustica, that numerous types of vines were common in Etruria, such as Pompeiano or Murgentino. Pliny the Elder described different varieties from Arezzo, such as Talpona nera (made into white wine), Etesiaca, Conseminea (excellent for everyday consumption), Sopina or Tudemis or Florentia, Perusinia (a red grape), Parana (in the Pisa area), and Apiana (a muscat grape that made a good sweet wine). The wines from Gravisca (the ancient port of Tarquinia) and from Statonia are described as excellent.

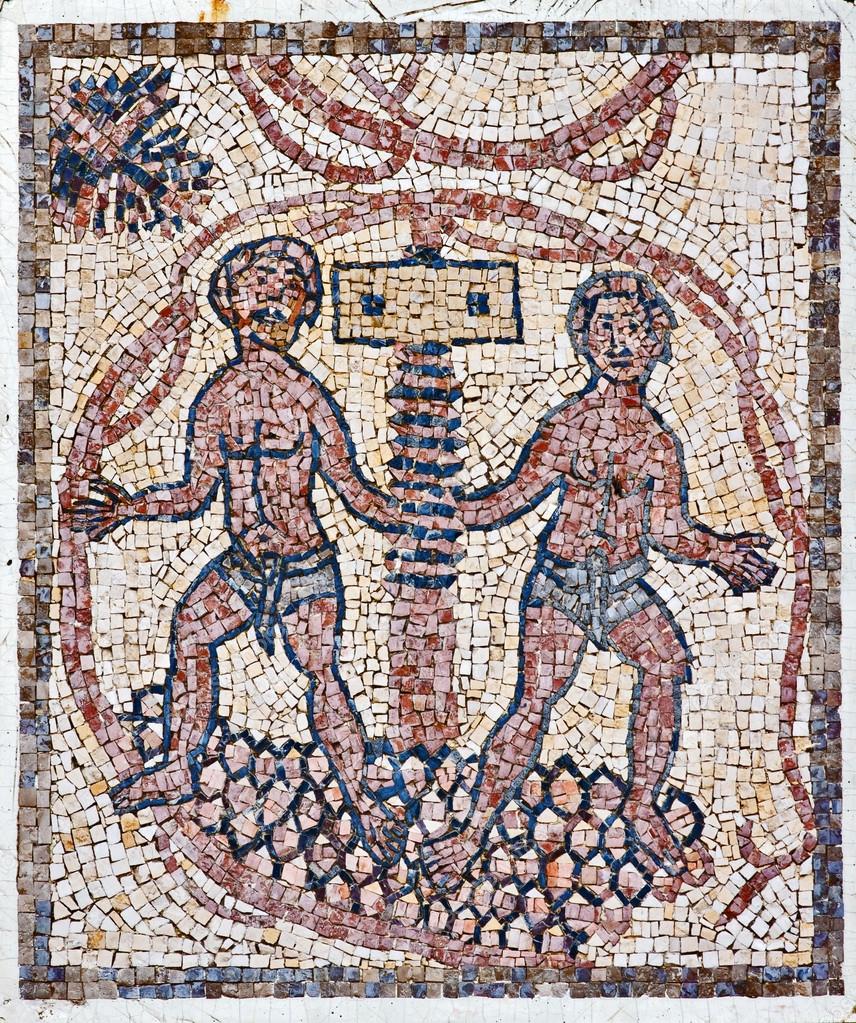

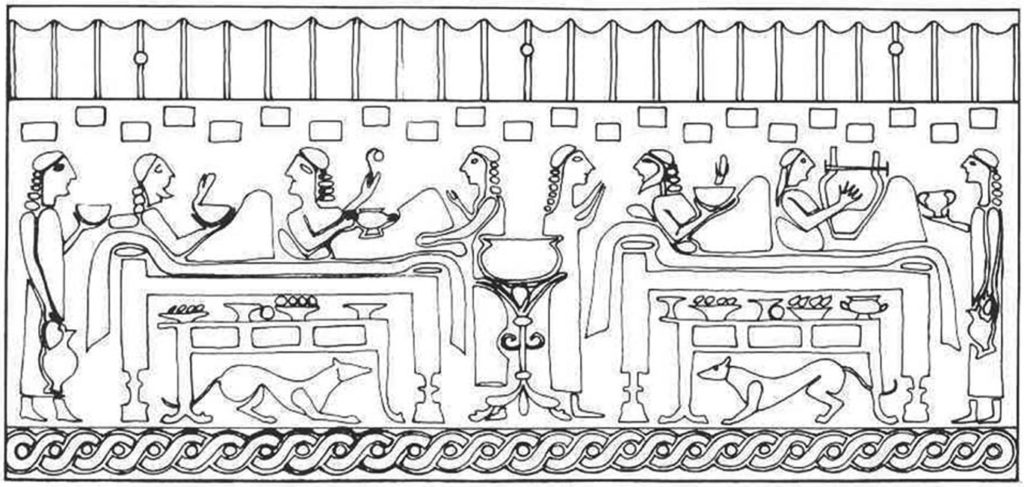

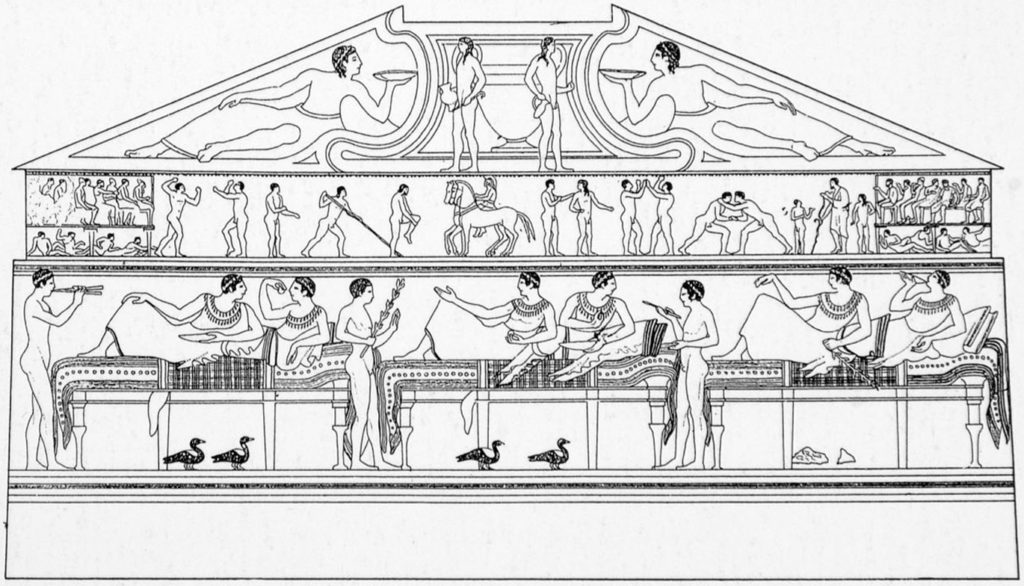

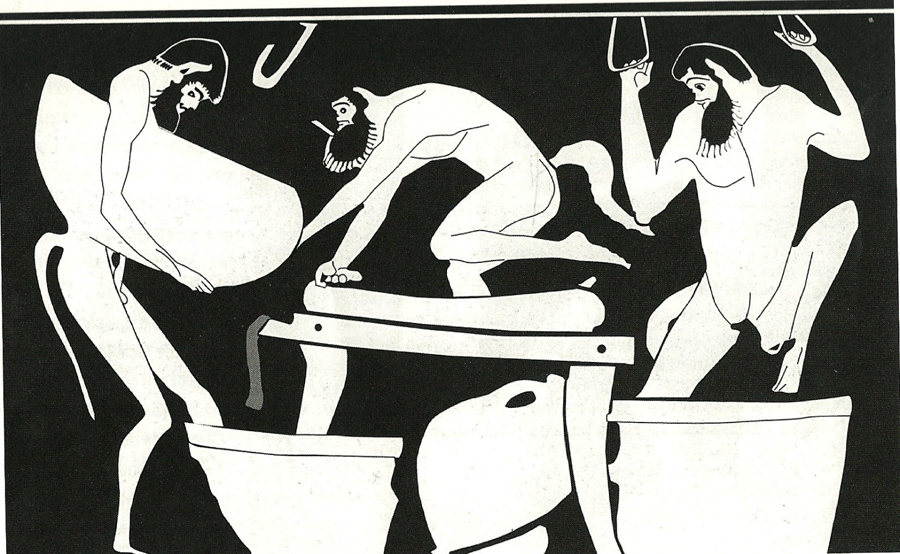

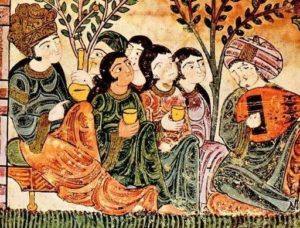

We better know how they consumed them. Rituals connected with wine seem to have already been present in Etruria at the end of the Bronze Age. However, contact with the Greek culture marked a profound evolution. The wine was more deeply linked to the religious dimension, used in a collective way in the celebrations of the Gods and in funeral ceremonies. The greater production made it even more available and became the protagonist of social rites, banquets and symposia (moments after dinner, where wine was drunk, attending music and dance shows, conversations and games). The commonalty probably also consumed a light wine, derived from the marc passed with water, frequent practice also in Roman times and until the nineteenth century.

The banquet had both religious and social meanings, being celebrated during funereal rites, as well as being staged as a symbol of wealth and belonging to an elite class.

In the first Greek models for marking aristocratic status, the reception of food and drink takes place while seated composedly at a table. This model appears in Etruria at least since the beginning of the seventh century. B.C. Beginning in the 6th century, we begin to see, still drawn from Greek cultural models, the figure of the banqueter, or diner, always half reclining on the kline, or dining couch, elbow resting on one or more cushions. In front of each diner were set some rather low tables, for food and wine cups.

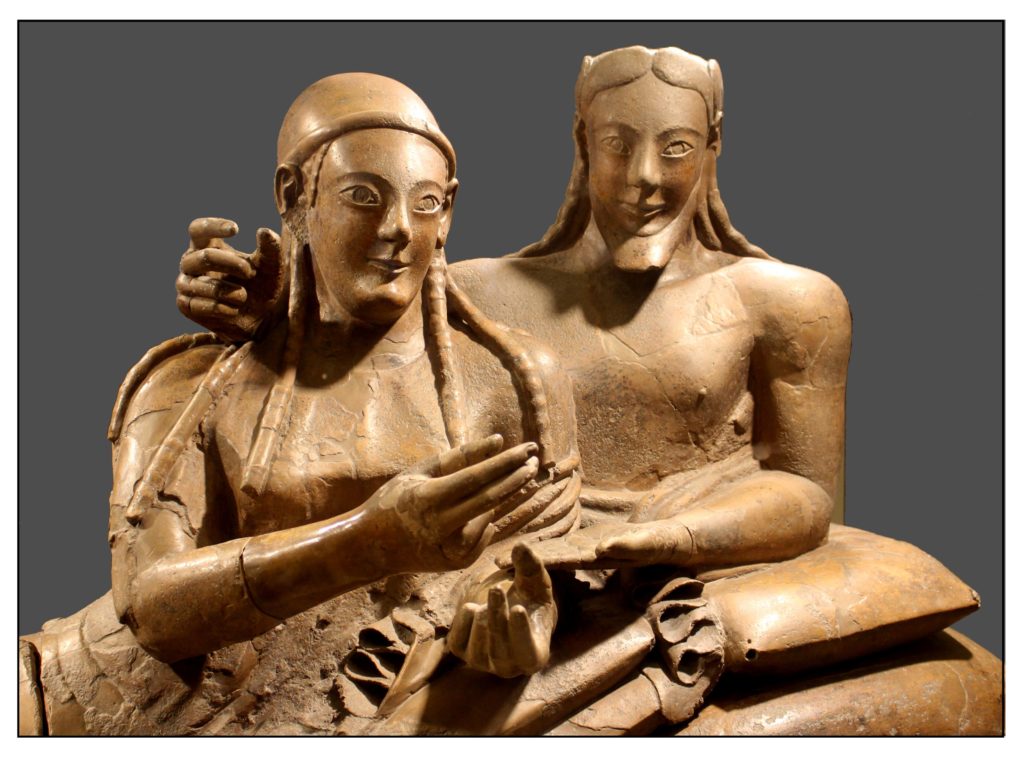

After 500 BC, women are represented at the banquets, sometimes reclining next to the men, sometimes seated nearby. This custom was exclusively Etruscan, since in the Greek world the symposium was solely a male affair, or at most open to the hetaerae, or courtesans. The Greeks, in fact, and the first Romans, regarded the female presence at Etruscan banquets as a sign of moral corruption. As a matter of fact, in the Etruscan world, women enjoyed a social and civic role far different from their subordinate status in Greco-Roman society. Female participation in Etruscan banquets had nothing whatever to do with the erotic or immoral. Rather, married couples took part in these meals, and were represented on sarcophagi and in frescoes as a symbol of family harmony.

The diners ate with their hands, often cleaning themselves with bowls of scented water and napkins. In the room there was pets (dogs, cats, chickens, ducks ...), who ate the remains of food that fell (or were thrown) on the ground. The banquet was always accompanied by music, especially from the flutes. There were also dance and juggling performances. There were also games: dice or the "tabula lusoria" (a kind of chess). The kottabos, arrived from the Greek Sicily, consisted in centering a target with the last drops of wine left in the cup.

Moralising criticisms were made by Greek and Latin authors about the luxury that marked Etruscan banquets, which featured precious vessels and embroidered textiles, a great number of servants. Someone tells that they banquet twice in a day! (The Greek and Roman lunch was very light and fast). The Romans went so far as to refer to the Etruscans as “slaves of their bellies” (gastriduloi), and the image of the obese Etruscan coined by Catullus became quite popular. This image, however, was by no means always negative, since in the ancient culture the “fat” person was he who could afford to be so, that is, it was a symbol of wealth and power.

How did they drink wine?

The wine drunk in antiquity was very different from what we enjoy today. It was concentrated, strongly aromatic, and high in alcohol. It was not drunk pure, but mixed with water, because it was considered barbarians to lose control in society. The wine was also sweetened and flavored. These practices were common in the ancient and medieval past, to cover defects due to limited production and conservation techniques.

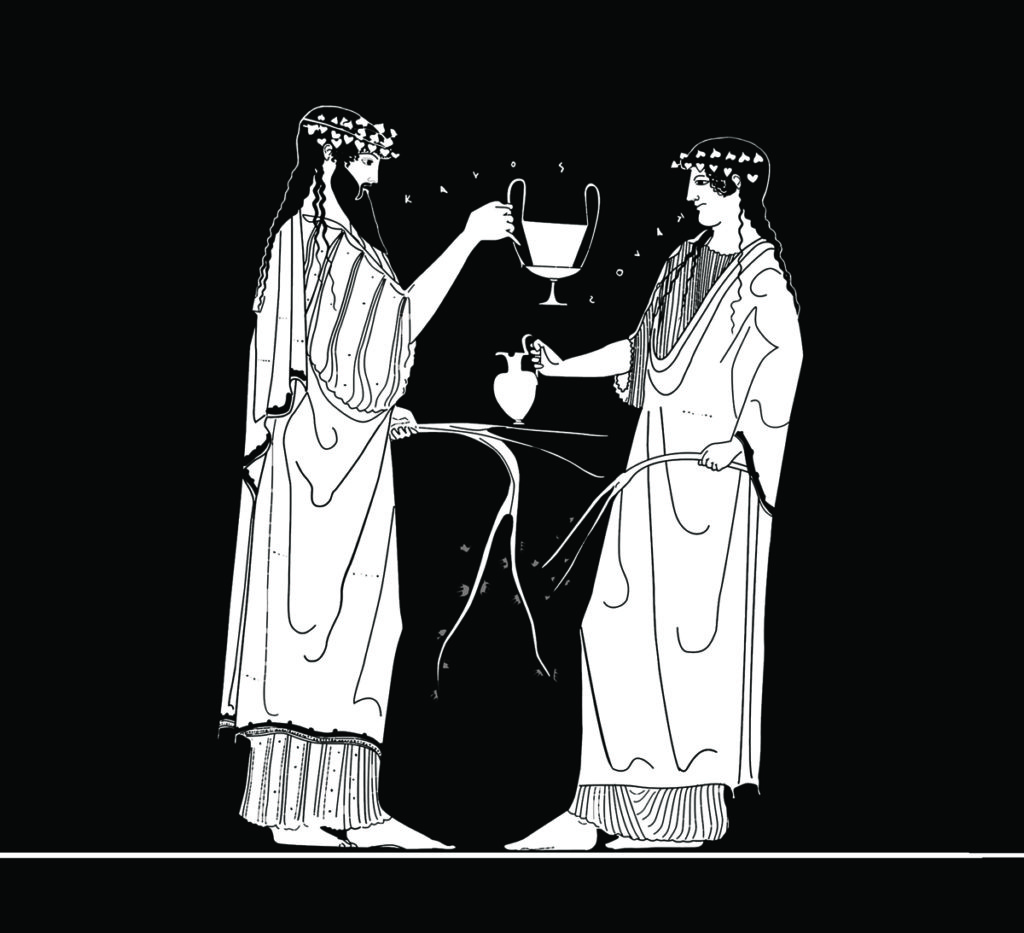

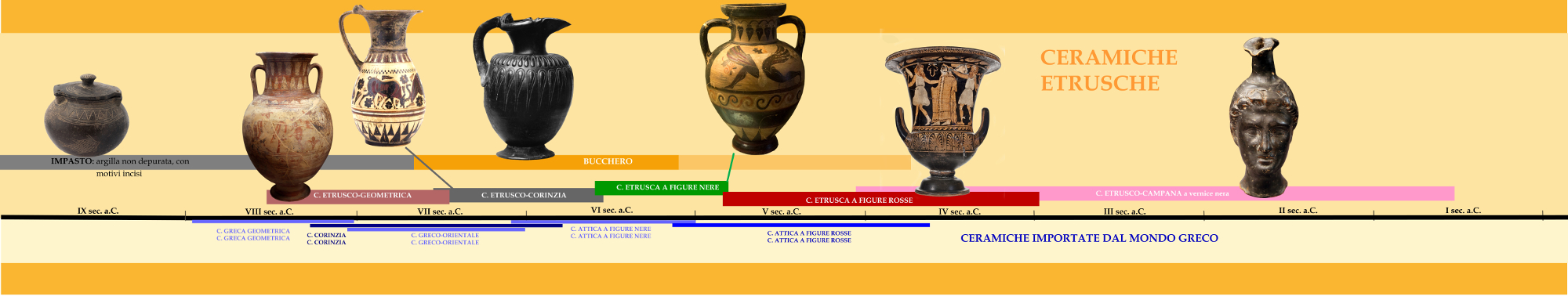

The various utensils used for wine and table were in ceramic or bronze. For them, archaeologists use Greek names because the Etruscan name is often unknown or uncertain.

In the centre of the room, there was a service table with the wine container (krateres), recognizable by the wide mouth. Near, there was a large amphora (hydria) for water, that was served at table with small buckets (situla). The wine was mixed with water in the krater. They used cold or hot water, according to the seasons. Then, they mixed also honey, herbs, flowers, spices, resins, etc.

The grater also belonged to the symposium supply, which was used to grate spices, roots or probably (as happened in the Greek world) cheese. From the crater the wine was then drawn with some ladles or cups like the kyathos, of typically Etruscan style, halfway between a cup for drinking and one for drawing.

The grater also belonged to the symposium supply, which was used to grate spices, roots or probably (as happened in the Greek world) cheese. From the crater the wine was then drawn with some ladles or cups like the kyathos, of typically Etruscan style, halfway between a cup for drinking and one for drawing.

The wine was poured into service jugs (oinochoe, another original Etruscan shape) or directly in the cups of the guests. It was also filtered with a strainer to eliminate turbidity.

To drink, the Etruscans used different ceramic cups, as the simple calyx (called thavna). An imported shape was the kylix (in Etruscan: culichna). The kantharos had two high handles (in Etruscan: zavena).

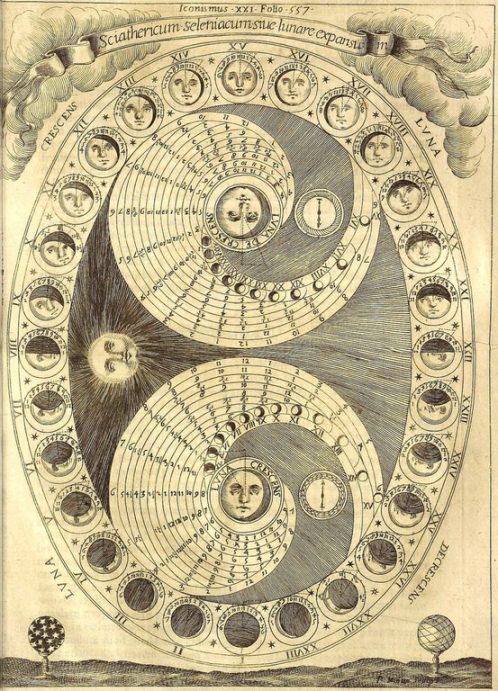

Wine was linked to the religious dimension not only in consumption at funeral banquets or in sacrificial rites.The Etruscans considered control over the cultivation of the vine so crucial that the augurs, the priestly class, were the custodians of knowledge concerning the working of the vineyards, the determination of the orientation of the vine-rows, and the magic rituals to ward off bad weather. Pruning too possessed a high symbolic charge. As a form of control and regulation of the vine’s crop, the Etruscans connected it with personal worth and kingship. The pruning knife found in Iron Age tombs between Novara and Verbania represented not the tool itself but ownership of vineyards. Virgil, in describing the Latin ancestors of Augustus’ lineage, names Sabinus and identifies him as a cultivator of vines.

Etruscan magical practices were saved in Roman epoc, for exemple during the Vinalia Rustica, festivals celebrated in August 19. The August festival featured rituals and magic practices aimed at warding off any weather disturbances that might threaten the harvest. As an example of these practices, Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, mentions the placing among the vines of an artificial cluster of grapes, which was intended to attract to itself damaging influences and thus save the rest of the crop. On the same day, the priest of Jove, the flamen dialis, celebrated the auspicatio vindemiae, and Cicero cites the auguratio vineta, rites meant to ensure a good harvest. Cicero, in his De Divinatione, attributes the origin of this “scapegoat cluster” to Attus Navius, who was of Sabine origin and a famous augur in the time of Tarquinius Priscus. When Attus Navius was a young swineherd, he lost one of his pigs and promised that if he found it, he would give to the god the largest cluster of grapes from his vineyard. Upon finding the errant animal, Attus Navius stood in the centre of his vineyard, divided it into four sections in accordance with directions in the Disciplina Etrusca, and then interpreted the flight of birds he observed. Since the birds gave inauspicious indications for the first three areas, he searched in the fourth section and found there a cluster of wondrous size.

There was two Etruscan divinties connected to the vine and wine:

TINA/TINIA/TIN. He was the highest Etruscan divinity; his primary attribute was the thunderbolt. Tina was not solely a god of the heavens; even in the beginning, he was linked to the plant world, and in particular to the culture of the vine. Pliny tells us, for example, that in Populonia there was an image of Tina sculpted from a large vine trunk. Later, he was assimilated to Zeus/Jove. In Rome, the festivals preceding the harvest were dedicated to Jove.

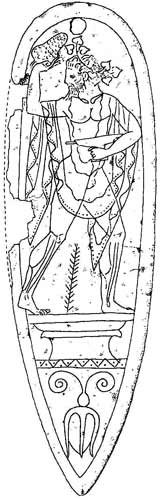

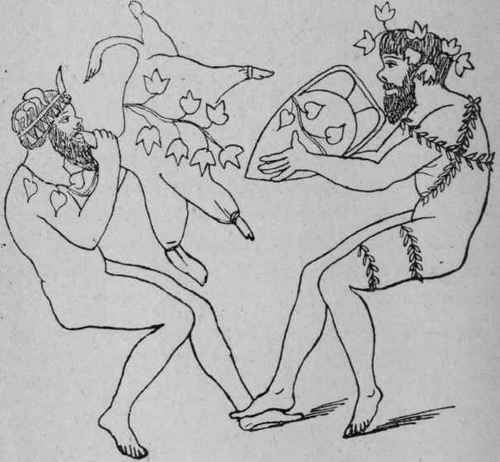

FUFLUNS was an Etruscan god, whose name is connected to the root puple, or young shoot, the same term from which the name of Populonia (Pupluna, Pufluna) derived. From the mid-6th century on, Fufluns took on the iconographical traits of the Greek Dionysos, who, under the epithet Dionysos Bakchos, gave rise to the Latin Bacchus. The artistic representation of Fufluns followed the figural canons of Dionysus: the kantharos, or drinking cup, and vine shoots, or parading with maenads and satyrs. Beginning in the 4th century, the identification became even more pronounced. The god was represented as a beardless youth, and the legends from the Greek myths were incorporated: his birth from the thigh of Zeus, his infancy at Nyssa, his encounter with Ariadne, etc.

THE DIONYSIAC RITES The influence exercised by Greek culture brought about as well the introduction into Etruria of the Dionysiac rites. This cult reached the apogee of its popularity in Etruria in the 4th-3rd centuries, so much so that colleges of Bacchantes were organised. Livy argues that it was precisely from Etruria that the Dionysiac rites arrived in Rome, which were subsequently prohibited by the Senate in 186 BC, as injurious to public order and morals.

These rites have often been misunderstood as simple sexual excesses and wild behaviour. In fact, Greek philosophy believed that wine unleashed a liberating and stimulating power in its devotees. The ecstasy that is achieved at the apex of Dionysiac frenzy is a form of higher awareness, and a means of uniting oneself with the divine. Wine was defined as “nectar of the gods” because it was considered a true and effective symbol of the sacred.

Nevertheless, the gift of Dionysus was ambiguous. On one hand, it unleashed vitalistic energy, but on the other, it induced a frenzy that could lead to death. Dionysus himself is thus a contradictory divinity, a god of vitalistic inebriation brought on by wine, but also “terrible for his irresistible power” (The Bacchants, Euripides). Dionysus is a saviour god, in fact, having been “born twice, descending to the underworld and returning hence alive.”

“mortem moriendo destruxit, vitam resurgendo reparavit”

In this way he reaffirmed life by means of death. Wine represented this death and resurrection of the god, since the juice of the grape was killed by the fermentation but then regenerated itself as a beverage with higher powers. For this reason, the sacred fury wine unleashed did not represent chaos, but opened to the cosmos, that is, to life over death.

Attilio Scienza presents his last work: "La stirpe del vino" (The bloodline of wine)

On Tuesday 4 December at the bookshop Hoepli in Milan, at 6.00 pm, our prof. Attilio Scienza will present, with the co-author Serena Imazio, his new book "La stirpe del vino" ("The bloodline of wine") Ed. Sperling & Kupfer.

In this book they tell about the origins, relatives (sometime unimaginable) and geographic travels of the main varieties of grapes, through history, myth and science,

Isabella Bossi Fedrigotti (Italian writer and journalist) will also speak. Maria Grazia Pennino (Sommelier AIS) will support the tasting of some of our wines and other estates (Bellavista from Franciacorta and Banfi from Montalcino) who kindly offered some of their best products.

Wine and the Etruscan III: the production

So far, we have learned to know the Etruscans and their viticulture, based on the "married vine". Now let's talk about wine production.

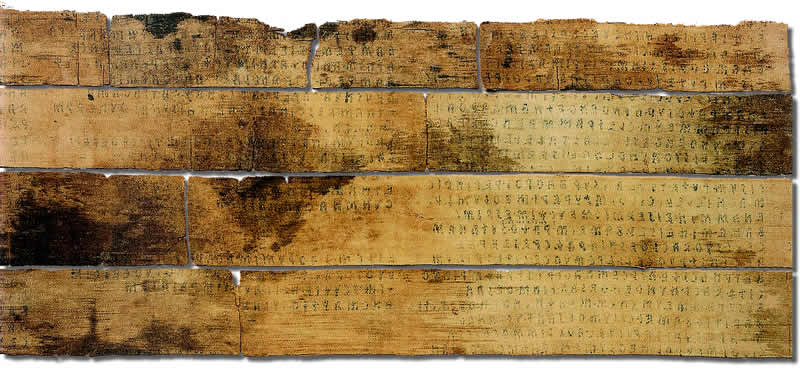

As for viticulture, even when we talk about ancient winemaking in Italy, we only allude to Roman wine. Yet the Romans also learned also winemaking from the Etruscans. The word vinum, wine, is passed to the Latin from the Etruscan. It then has remained in modern European languages (Italian and Spanish vino, French vin, English wine, German wein, etc.). However, its origin is even older and it comes from far away. It seems to be a sort of "traveling word" that most likely followed the same historical-temporal path of the vine and wine, from East to West:

winuwanti in ancient Licaonia (Caucasus)

wnš / wnšt in ancient Egyptian

wo-na-si or wo-no in Mycenae

foinos-voinos in Aeolian dialect

vinom in faliscan (ancient language of the Falisci, who lived in the southern part of Etruria, between the Cimini mountains and the Tiber river, in the area of present-day Civita Castellana)

vinum in Etruscan and then in Latin.

The current Georgian (Caucasus) gwino marks the starting point.

The Etruscan word vinum therefore derives from a foreign influence, from Greek culture. It is therefore thought that it came into use only from the 8th century B.C. There is a native word for this drink: temetum. This belongs to the protohistoric roots of the Etruscan and Latin peoples. However, the word vinum will be the winner.

After this linguistic digression, we come to our point.

How did the Etruscans make wine?

It is not easy to answer this question. We know some things for certain, we can deduce others by affinity from other Mediterranean peoples. We can surely get a lot of information from Roman authors. The productive techniques of Archaic Rome tell us much about Etruscan oenology.

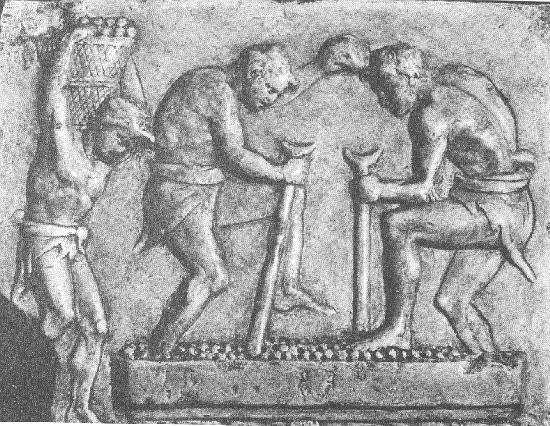

In very primitive times, in general, scholars hypothesize that grapes were crushed in small containers, simply squeezed by hand or using stones as pestles.

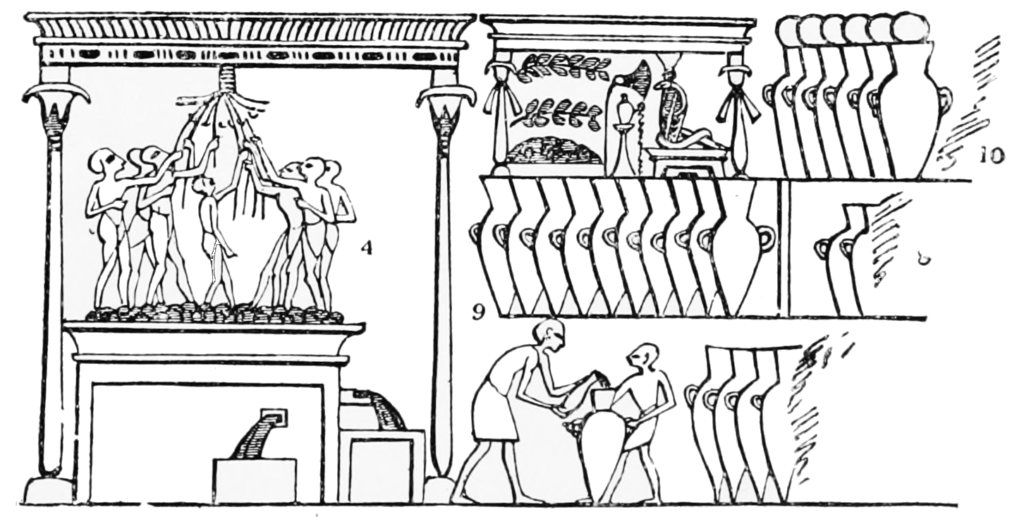

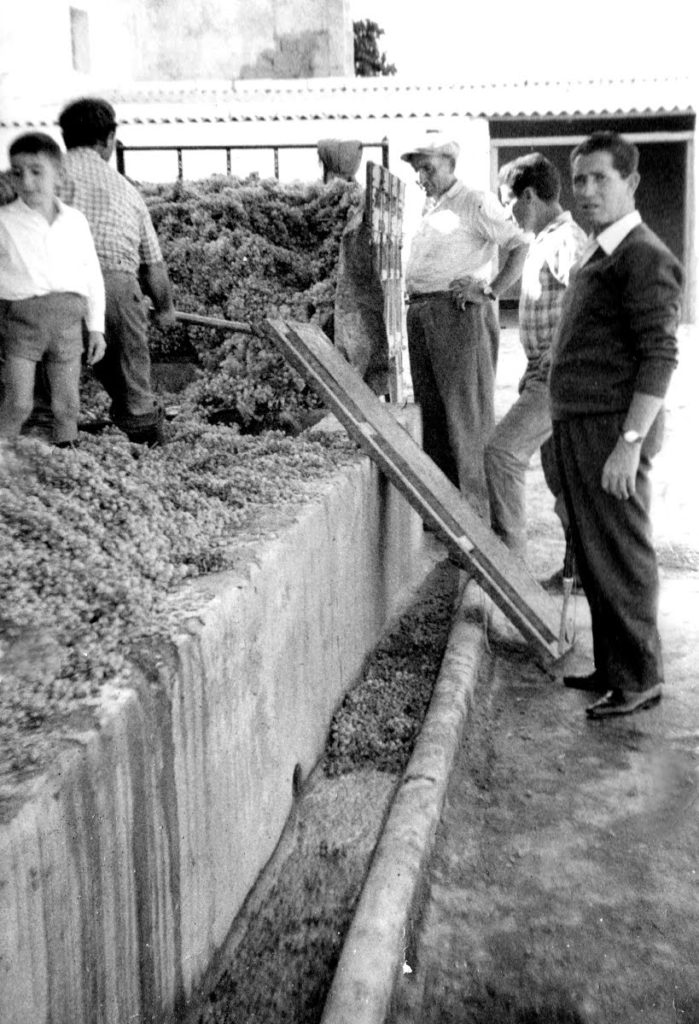

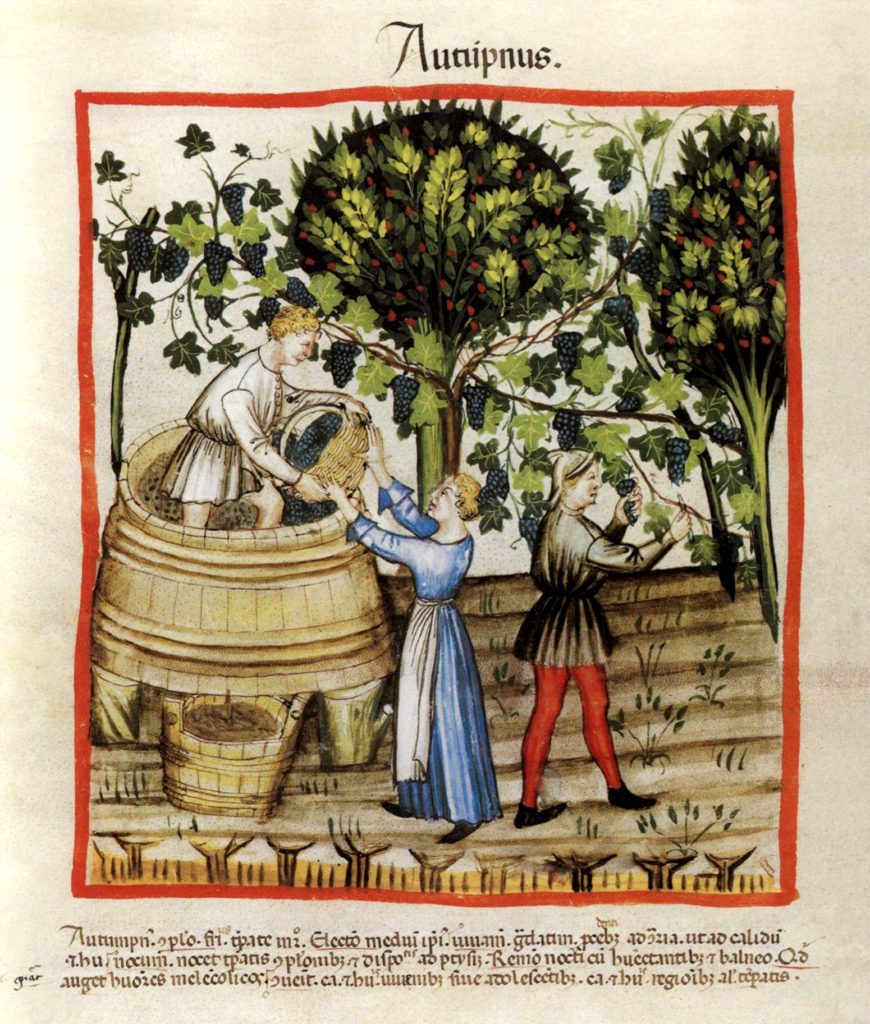

However, when the man began to represent the scene of vinification in frescoes or on found vases, the use of pressing with feet in larger containers prevailed already.

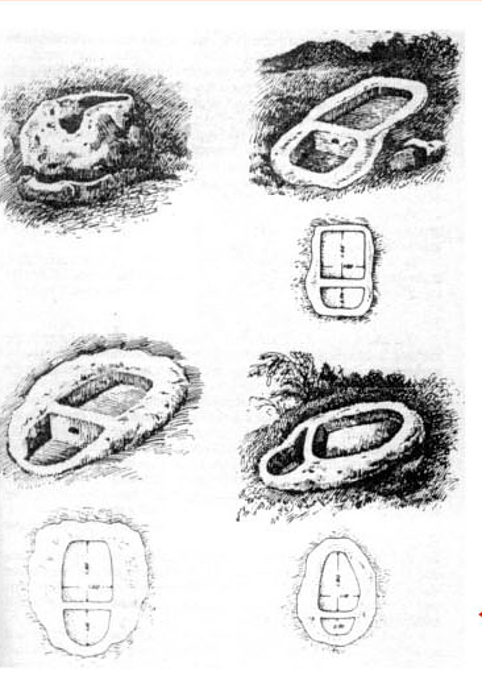

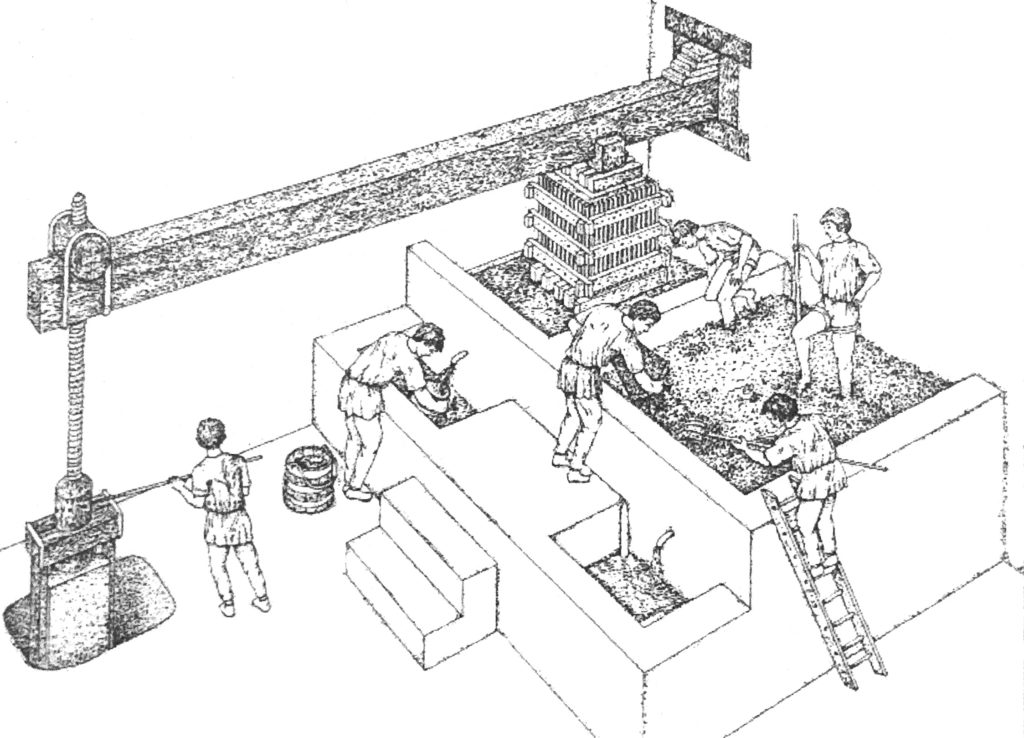

We know for sure that, at a certain point, the Etruscans began to crush the grapes into rough vats carved in the stone, called PALMENTI (the singolar is palmento). They were dug into natural rocky outcrops. These vats, before the vine domestication, were realized near the wild vines in the woods. With the beginning of cultivation, the palmento was made in the vineyards. It was probably covered with light structures, made by canes or other, to shade them or to protect them from light rains. We know it because four holes were found in some of them, also dug into the rock, as bases for housing the support poles of a canopy.

It is thought that stone vats appeared more or less from the first millennium BC. Rare examples date back to the Bronze Age but they become more numerous later. Their dating, however, is not simple, because they were also used for centuries. In Italy, many ancient palmenti were been used by local farmers until the Middle Ages and, sometimes, even later, some even up to the mid-twentieth century.

The stone vats have been found in Tuscany, in the Marche, in Latium, in Campania, in Calabria, in Sardinia, as well as in almost all areas of the Eastern Mediterranean. They have also been found in the countries of the Western Mediterranean (such as Spain, Portugal and southern France) but these date back to Roman colonization.

On the other hand, except for rare exceptions, they are missing in the Greek colonies of southern Italy. It is thought, probably, that wooden containers were more used in this area, of which obviously there are no traces left. This system was the one most used also in the mother country. Infect, from the numerous harvest scenes on the vases, it is clear that in Greece, in archaic times, transportable wooden vats were mainly used, with legs, positioned directly in the vineyard.

In Crete, in the Bronze age, the depictions show the grape crushing with the feet in species of ceramic vats. Also in Magna Graecia there is evidence of lime-covered clay vats. Similar constructions, made with raw bricks, are also found in the Phoenician-Punic world and in Egypt.

Returning to the Etruscan stone vats, these were dug inside rocky outcrops composed by easily workable material, often of volcanic origin, such as peperino or tuff. These materials are very perishable by erosion; they were been the cause of the loss of mostly of the ancient palmenti, became over time unrecognizable.

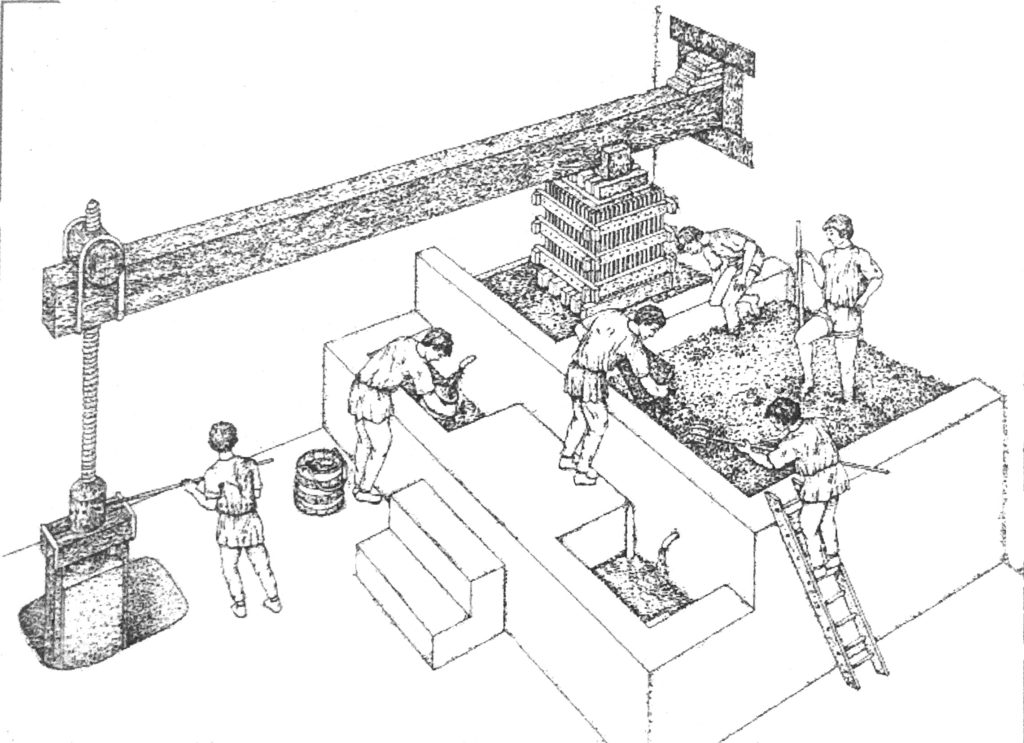

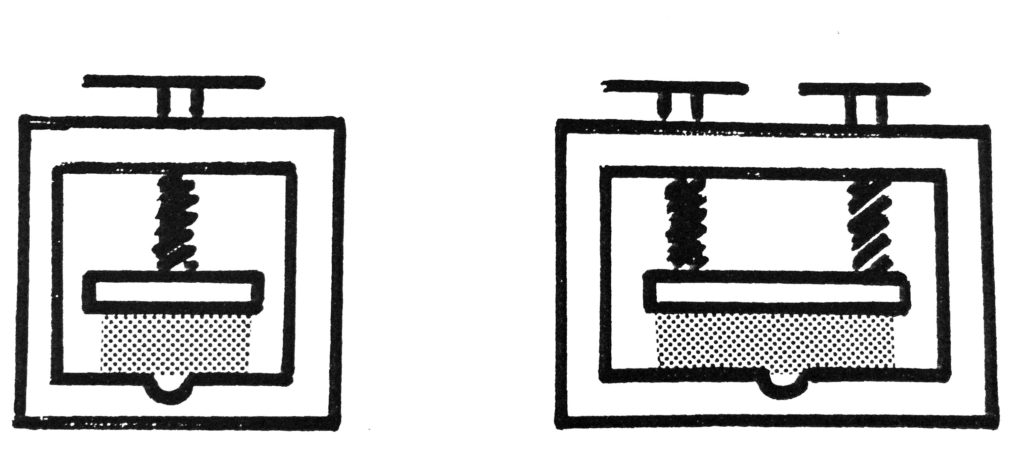

The palmenti were formed by a cavity or, more frequently, by two, communicating through a drainage channel. The grapes were crushed with bare feet in the upper vat. This is (more or less) square in shape and not too deep, with the drainage channel closed with clay. The crushed grapes were left to rest. Then the communicating hole was opened and the liquid was left to filter in the vat below. This second vat was deeper and smaller, often semicircular. Here fermentation was completed. The must could also be transferred and fermented in terracotta amphoras, those that the Romans will call dolii (dolium, in the singular).

The pomace, left in the upper tank, was crushed to recover the must-wine contained. The most primitive systems were based on the squashing made with stones or pieces of wood resting on. Later, probably, grapes were squeezed in sacks. At the end, the pomace was washed with water, producing a very light wine for the lower classes (the Romans call these wines deuteria or loria; this practice will remain common until modernity).

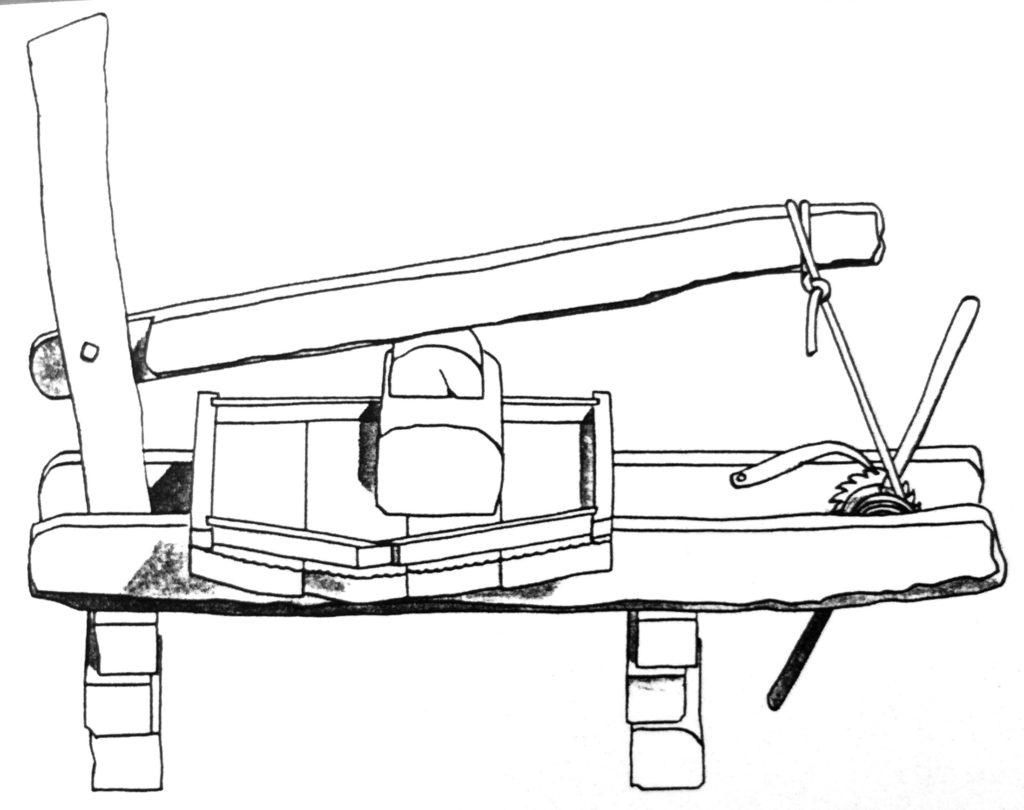

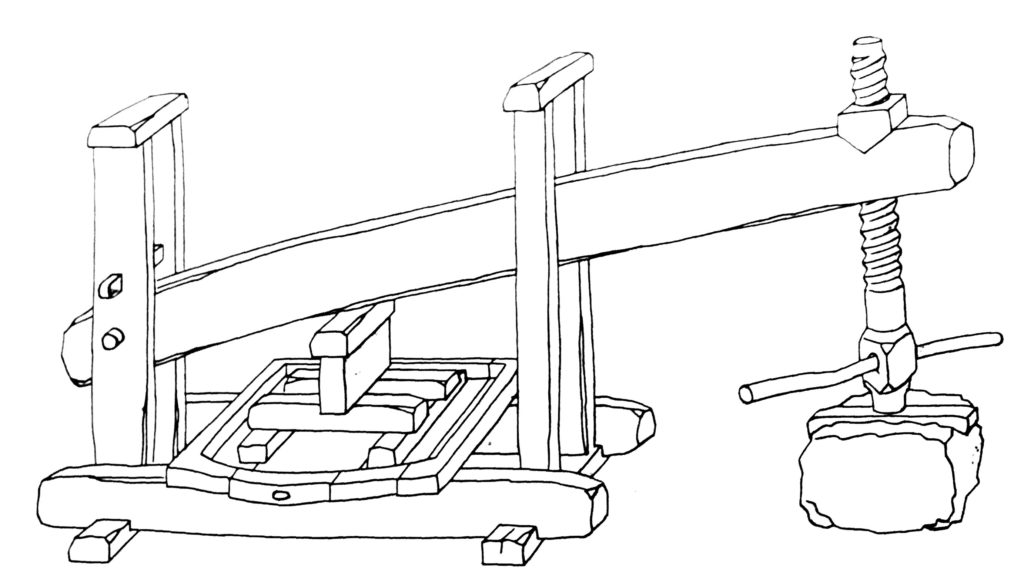

In Greece, rudimentary wine presses are documented on amphorae from the sixth century BC. They are made by a trunk lowered by human force or weighed down with stones. It is impossible to find remains of these presses, because they are made of rough materials (stones) and perishable materials (wooden parts). However, it can be assumed that they were also used by the Etruscans, by themselves or for Greek influence. However, the first documentation of similar wine presses in Italy is due to Cato, in the II century B.C.

The wines were kept in terracotta containers, like most of the products in the ancient era. Very probably also wineskins were used, of which there are no remains, but which are often depicted.

In successive epochs, the passage towards a more evolved wine production is marked by the realization of the palmenti directly in the farms. Meanwhile, Etruria was gradually annexed by Rome, in a period ranging from the 3rd to the 1st century BC. From the late Republican age onwards, the methods of wine production in Italy are widely known and documented by Roman authors.

At this stage masonry vats appear, which will remain typical of many parts of Italy, almost to the present day. They were made of stones or bricks cemented with mortar and then plastered with waterproof mortar. The grapes were pressed with the feet and the must was left to settle. Then it was fermented in cisterns in masonry or in amphoras (dolii), lined internally with pitch. In all these ages we cannot exclude the use of wood, of which no traces remain.

The first wine obtained from the harvest was usually consumed immediately, while the remainder was poured into terracotta containers with the internal walls covered with resin or pitch. The wine was left to rest, foaming frequently; it was decanted in spring and poured into transport amphorae. The pomace was squeezed into lever presses, operated by ropes pulled by a winch. In the largest farmers, from the first century BC, there were also large presses with lever and screw, with big stones that served as a counterweight.

From the 1st century AD the central screw press was invented, safer and more manageable than the lever one, even if less powerful. It was made entirely of wood and therefore there aren't remains of the ancient era. We have this information from documents, especially from the testimony of Pliny (Naturalis Historia). For this reason, it is also called "Pliny's press".

The Pliny's press will make a remarkable leap only when it will can pass from the wooden gears to iron ones, which will happen only in the second half of the nineteenth century. In Roman times and in those to follow, iron was a very expensive material (without considering the technical difficulties of threading it regularly). No one would have thought of using iron where wood could be used. Only in the nineteenth century, thanks to the greater availability and the lower cost of the metal, its used began for the gears and then for the whole tool, allowing the definitive abandonment of the bulky (and difficult to handle) lever presses.

The wine production technique of the late empire will be the one that will remain substantially unchanged in Italy (and other areas of the Empire) for centuries to come. The various systems explained so far coexisted, some very archaic and others very advanced. We can imagine the great landowners who has made themselves build avant-garde and very expensive wineries. They could be imitated by local notables, but certainly not by other small farmers, with fewer financial resources, who continued to produce wine with simple tools, easy to produce by themselves.

Summarizing, the grapes were pressed with the feet in stone or masonry palmenti. Must was fermented in masonry tanks or, above all, in terracotta dolii. In this era, more and more wooden containers (documented) appear for crushing, fermentation and transport, which will become prevalent from the Middle Ages onwards. The pressing was done in the various types of wine presses described above, but mainly with lever presses with ropes and winch. Although this was an outdated technology, it remained the most widespread because it was the simplest and least expensive. The most modern systems of lever-screw or central screw presses, on the other hand, required skilled craftsmen to make them and quality timber, so they were only present in the richest wineries.

From the Middle Ages on, these same systems will remain. Almost all the terracotta containers will disappear and the wood will prevail. The palmenti and the different types of presses will remain. For substantial changes from these models, we will have to wait until the nineteenth century.

Wine and the Etruscan (II): the "married vine", three thousand and more years of viticulture and art

The Etruscans were the first winegrowers in Italy, beginning from the wild varieties.

The wild grapevine is a local plant in the Mediterranean area. In the more ancient times, people began to gather its fruits in the woods.

The wild vine (Vitis vinifera sylvestris) is a native species of the Mediterranean area and, above all, in Italy, it finds its ideal conditions. Even today, it is possible to find wild vines in our woods (even if you have to make attention to distinguish them from vines became wild, from old abandoned vineyards). The varieties we cultivate today derive from the wild vine, modified through millennia by selections and crossings carried out by man.

Returning to the Etruscans, scholars hypothesize that they cultivated the vine since the Bronze Age, however at least from the twelfth century B.C.

Later, with the development of civilization, being great navigators and merchants, they had increasingly intense contacts with the peoples of the eastern Mediterranean (especially with the Greeks), where culture and viticulture techniques were already more evolved. This allowed them to refine production techniques, to import new tools and new practices of working. New oriental vine varieties were also imported (whose process of domestication began in a much more remote era in the Caucasus area). These new vines were cultivated and crossed with local varieties too.

Thanks to these influences, the primitive Etruscan viticulture grew and grew over the centuries, and wine production increased in quantity and quality. So, from the 6th century B.C., began also the overseas trade (which we will discuss later).

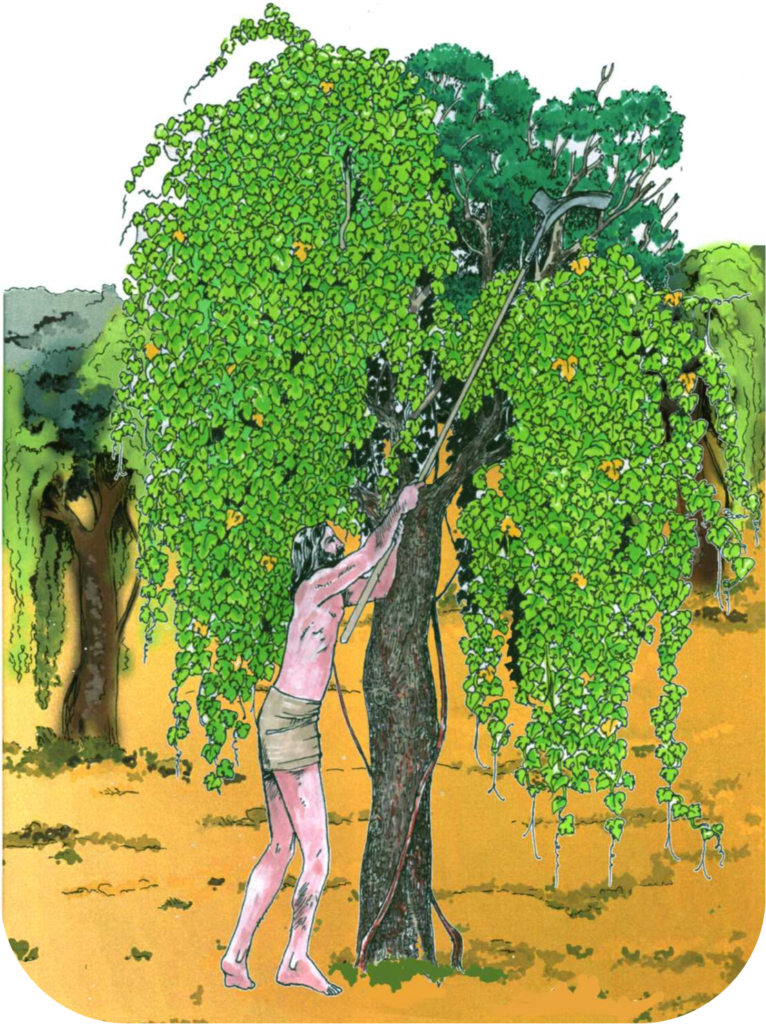

The Etruscans cultivated vines in the same manner they saw these plants grow wild in the woods. The vine is a climbing shrub, a species of liana. In a wood, its natural environment in our latitudes, it tends to climb up a tree to reach the light as possible (it is very heliophilous specie). However, it is not a parasite: the vine does not weaken the tree on which it clings.

Today the Etruscan cultivation system name is “married vine”, "vite maritata" in Italian. The vine is like "married" to the tree. This definition is not Etruscan but was born later, as we will see. The Etruscan word was “àitason”.

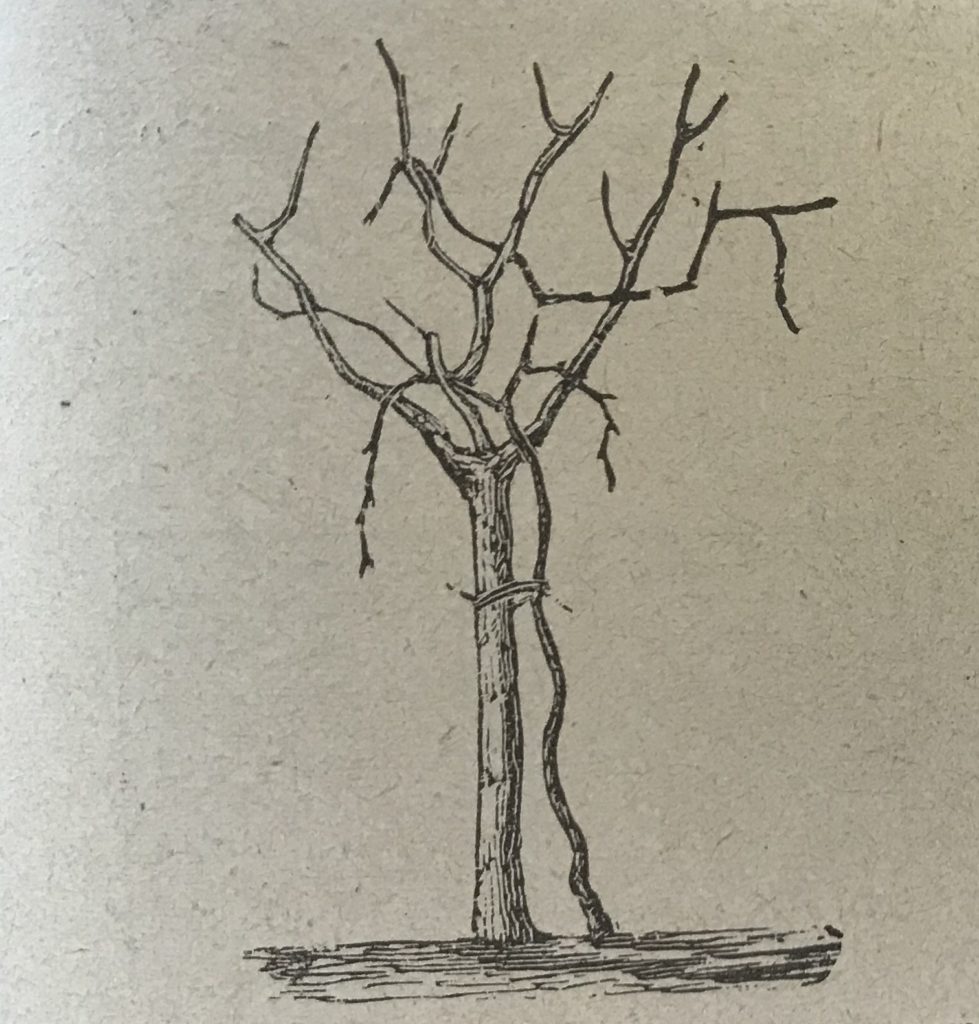

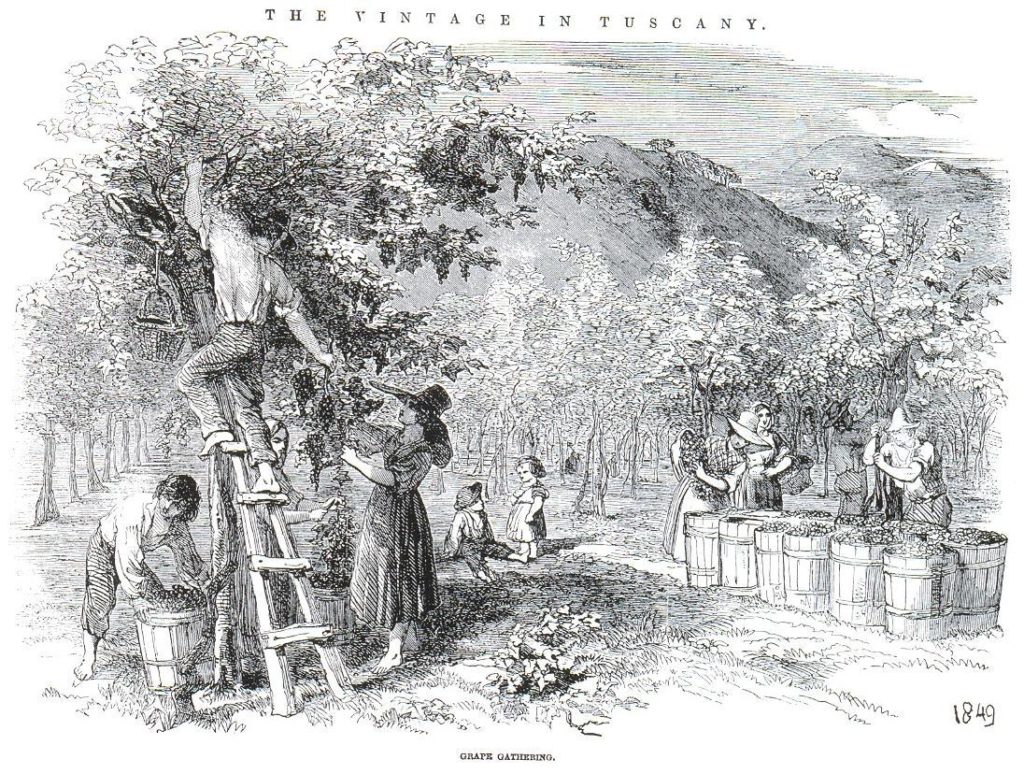

The vines were married to poplars, maples, elms, olive trees and various fruit trees. Originally they were not pruned, later they were subject to long pruning. The vine therefore tended to grow a lot, to have very long shoots. They picked up the grapes with the hands or with sickles, with ladders or using instruments with a very long handle.

The growing of vines in Etruria was not specialized: there was not a vineyard, as we understand it today. Instead, the vines were promiscuous with other crops (alternating with cereal fields, olive trees, fruit trees, etc.).

The “married vine” has remained in the Italian wine culture until almost our days, in all those territories where in ancient times the Etruscan civilization had arrived.

The Etruscans, from the original area of Tuscany and upper Lazio (called "Historic Etruria") then widened their borders, expanding to Campania, to the south, and Emilia Romagna to the north. In Campania there is still today the border between the Etruscan wine culture (more to the north) and the Greek one (the vine-training system called "alberello"). In the latter, the vine was cultivated as a low stump, without support or with "dead" support (a pole). The Sele River marked, more or less, this border.

The Etruscans brought their advanced wine culture in the conquered lands, spreading it also to neighboring peoples, such the Cisalpine Gauls (the Cisalpine Gaul corresponds to a good part of the current northern Italy).

The Etruscans transmitted a great part of their culture to the nascent Roman civilization, including viticulture and wine production. According to the tradition, king Numa (one of the seven early kings of Rome), Etruscan by birth, taught the viticulture to the Romans.

In fact, in ancient Roman time, as witnessed in the De Agri Culture by Cato (II century BC), the cultivation of the vine was made in the Etruscan manner, marrying it to the elm or fig tree. The Etruscan àitason became the Latin arbustum (vitatum), which Cato sometimes also calls vinea, as well as Cicero does.

Varro, however, in De Re Rustica (39 B.C.) begun to distinguish two different forms of vine cultivation. Probably, in his time, a new form of viticulture emerges in Roman territories, the Greek one, already mentioned above. The word arbustum remains to indicate the married vine. Vinea becomes the term to indicate this new cultivation system. Both of them belong to the general category of vinetum.

Virgil, in the Georgics (29 B.C.) describes the viticulture of his land (Mantua) and tells that the vines were married to the elm.

Columella, in the De Re Rustica (65 AD), the first real agrarian treatise in history (it will remain the basic text for all the centuries to come, until at least the 18th century), describes the different systems of Roman viticulture. However, the increasing prevalence of the vinea to the detriment of the arbustum emerges, because the first guarantees viticulture that is more specialized.

Pliny the Elder (Naturalis Historiae, 77 A.C.) tell us about the viticulture of Campania at the time, with vines married to the poplars, even very tall, especially in the area of Aversa. He distinguishes the arbustum italicum, where the vines rise on the single tree, from the arbustum gallicum (so called because it was very common in Cisalpine Gaul), where the vine shoots are passing from one tree to another and forming rows. Pliny was also a wine producer: he sold large quantities of it in Rome, producing it in his farms in Campania, from married vines.

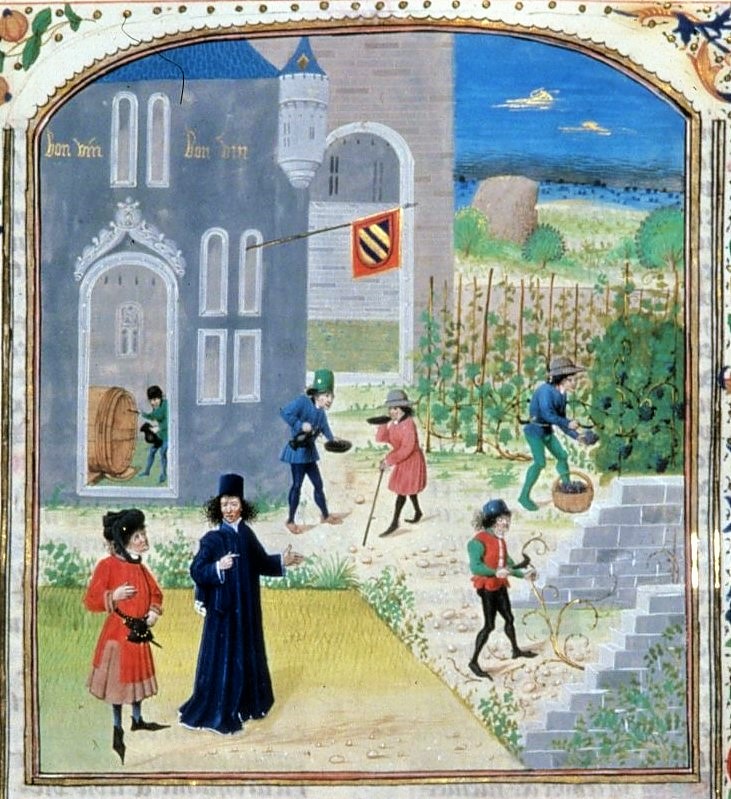

The married vines also return in to less relevant works of the late empire, such as the Opus Agricolturae by Palladius (4th century AD) and the Geoponica by the Byzantine Cassianus Bassus (6th century AD) which advises them in damp soils. In medieval period, we can find them in the work by Crescenzi (from Bologna), the only relevant medieval agricultural text of the European Middle Ages (1486).

In 1644, the Bolognese agronomist Vincenzo Tanara describes the two main systems of married vine of his time, which correspond to the Roman systems. He calls them “piantata” (the arbustum gallicum) and “alberata” ( the arbustum italicum), terms still used in modern Italian.

For all the following centuries, these two systems dominated the viticulture of the Center and the North Italy, depending on the area. The alberata were plots with vines climbing single trees, randomly positioned in the field or with regular arrangement. Native from central Etruria, they remained traditional especially in Tuscany (with the name of “testucchio”) but also Lazio and Umbria. The piantate instead was formed by rows in the border areas of the fields or along the banks of the ditches. They were more widespread in the north-central part of Etruria and in the areas of expansion to the South. In fact, they remained traditional especially in the Po Valley and Campania.

Therefore, the married vine continued to be part of the Italian rural landscape even after the classical era and it was depicted in the art of all centuries.

These landscapes also fascinated the foreign travelers of the eighteenth-century who were making their cultural journey in Italy, which was considered indispensable in the youth formation of the educated European class at the time. The landscapes with the married vines are in many paintings of that period. They are also told in the travel diaries, such as by the French architect Jacques-Germain Soufflot in the mid-eighteenth century, visiting Paestum (Suitte Des Plans, Coupes, Profils, Elévations géometrales et perspectives de trois Temples antiques, tels qu’ils existoient en mil sept cent cinquante, dans la Bourgade de Pesto… Ils ont été mésurés et dessinés par J. G. Soufflot, Architecte du Roy. &c. en 1750. Et mis au jour par les soins de G. M. Dumont, en 1764, Chez Dumont, Paris, 1764), or by Goethe with his famous "Journey to Italy" (1813-1817).

The image so evocative of the vine that embraces the tree, however, did not remain confined only to agrarian contexts. He also lit the imagination of artists and writers, who gave them different symbolic meanings.

From the first century AD, the poetic metaphor of the vine and the tree (especially the elm) appeared in the Latin literature as a symbol of indissoluble love. The vine is "married" to the tree: hence the term vitis maritae (vite maritata, in Italian) which we still use today ("married vine") was born.

For example, Gaius Valerius Catullus identifies the vine and the elm as a wife and husband in the "Bridal Song of boys and girls" (Carmina, poem 62, translation by E. T. Merrill):

“… As the widowed vine which grows in naked field never uplifts itself, never ripens a mellow grape, but bending prone beneath the weight of its tender body now and again its highmost shoot touches with its root; this no farmer, no oxen will cultivate: but if this same chance to be joined with marital elm, many farmers, many oxen will cultivate it: so the virgin, while she stays untouched, so long does she age, uncultivated; but when she obtains fitting union at the right time, dearer is she to her husband and less of a trouble to her father.”

In the Metamorphosis of Ovid (XIV, 623 and following), this metaphor appears in the love story of Vertumnus and Pomona. Vertumnus was a God of Etruscan origin, also remained in the Roman religion. He was the God of the transformations (verto, in Latin, means in fact change): of the change of the seasons but also of the trade. The God fell in love with Pomona, a very ancient Latin goddess of the cultivation of the fruits, which, however, was unapproachable. He tried to reach her with different disguises, and he had succeeded when he took the form of an old woman. Then, he tried to convince her to abandon herself to love with various arguments, including the metaphor of the vine and the elm:

“There was a specimen elm opposite, covered with gleaming bunches of grapes. After he had praised it, and its companion vine, he (the “old woman”) said: ‘But if that tree stood there, unmated, without its vine, it would not be sought after for more than its leaves, and the vine also, which is joined to and rests on the elm, would lie on the ground, if it were not married to it, and leaning on it. But you are not moved by this tree’s example, and you shun marriage, and do not care to be wed. I wish that you did!”

(A. S. Kline's Version)

At the end of the speech, Vertumnus revealed itself. Pomona, struck by the words heard and the beauty of the God, gave in to love.

This story had great success in the Renaissance and it will remain a very frequent artistic themed until the eighteenth century.

Again, we find in Ovid (Amores, elegia XVI) this theme:

Ulmus amat vitem,

vitis non deserit ulmus;

Separor a domina

cur ego saepe mea?

(The elm loves the vine

The vine does not desert the elm;

Why so many times am I separated from my beloved?)

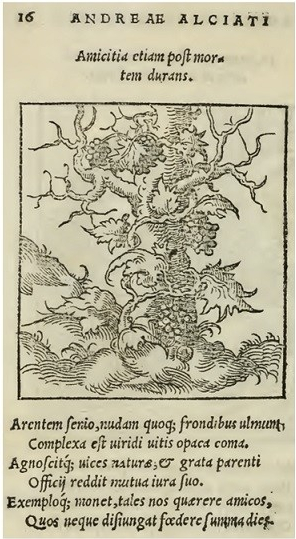

The theme of the vine married to the tree, however, reached its maximum diffusion thanks to the Milanese jurist Giovanni Andrea Alciato or Alciati (1492-1550). He published a collection of allegories and symbols (reproduced with woodcuts), explaining their moral value with short texts in Latin. The title was "Emblemata", published in Augsburg in 1531. It was an extraordinary success throughout Europe, with translations into Italian, French, Spanish, German and English. Alciato created a real new literary genre, of great success even in the following centuries, the emblem book.

Alciato reported the married vine as the emblem of Friendship and, in its purest form, of Love, with the Latin title:

"Amicitia etiam post mortem durans"

(Friendship that lasts even after death)

This interpretation was influenced by an epigram of the Greek poet Antipater of Thessalonica (1st century BC), in which a withered plane tree tells how the vine, climbed on it, keeps it green. Alciato, who is from Lombardy, corrects the Greek's error. The married vine was part of the agrarian landscapes of his native land and therefore he knew very well that it is the elm the ideal husband of the vine, not the plane tree.

Thanks to Alciato and to the success of the emblem book, the symbol of the vine married to the tree had an enormous diffusion and appeared in many artistic representations, in poems and literary works from all over Europe. The married vine of Etruscan, with Mediterranean origin, thus became a decontextualized cultural symbol.

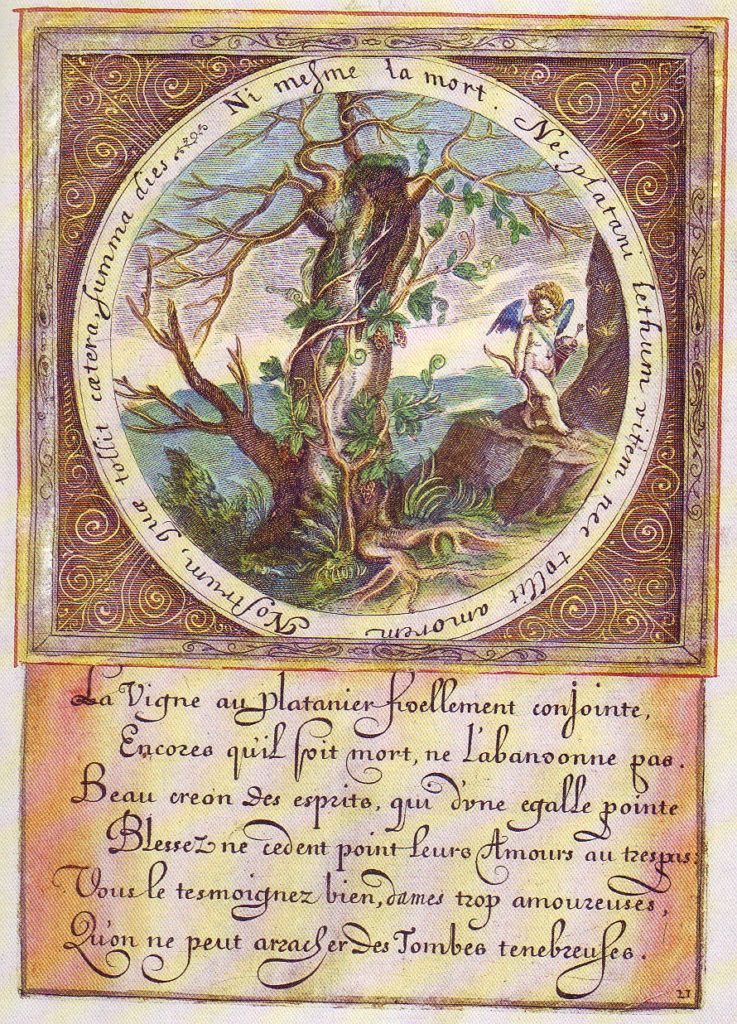

For example, the Flemish Daniël Heinsius, in Emblemata amatoria (1620), rather than to Friendship, returned to bind it to the Imperishable Love, as in the classical era. He returned to use the plane tree too, as in the original Greek epigram. The married vine is the emblem of an eternal love that goes beyond death, with the wording

"Ni mesme la mort", not even death.

It also became the logo of the Elzevier, publishers of Leiden (Holland) from 1580. The current Elsevier publishing house (refounded in the nineteenth century) is the world's largest medical and scientific publisher. Their symbol remains the original one, a life married to a tree, with the meaning of the alliance between learning and literature.

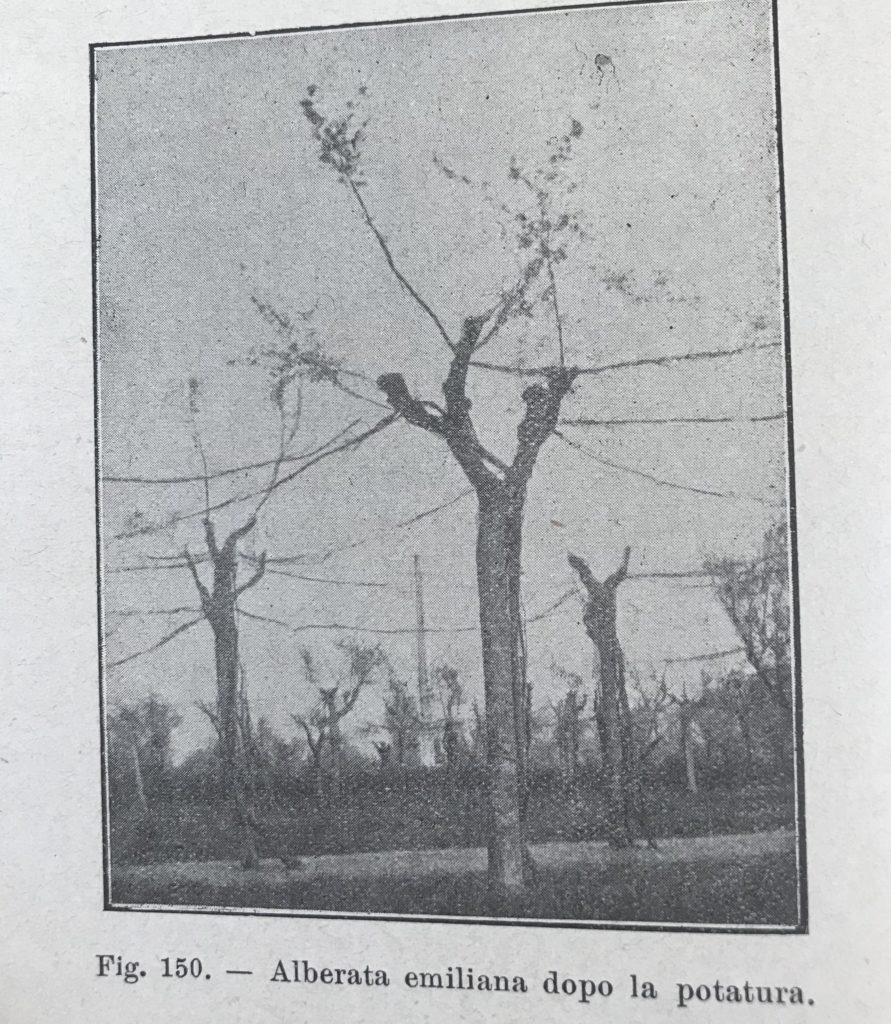

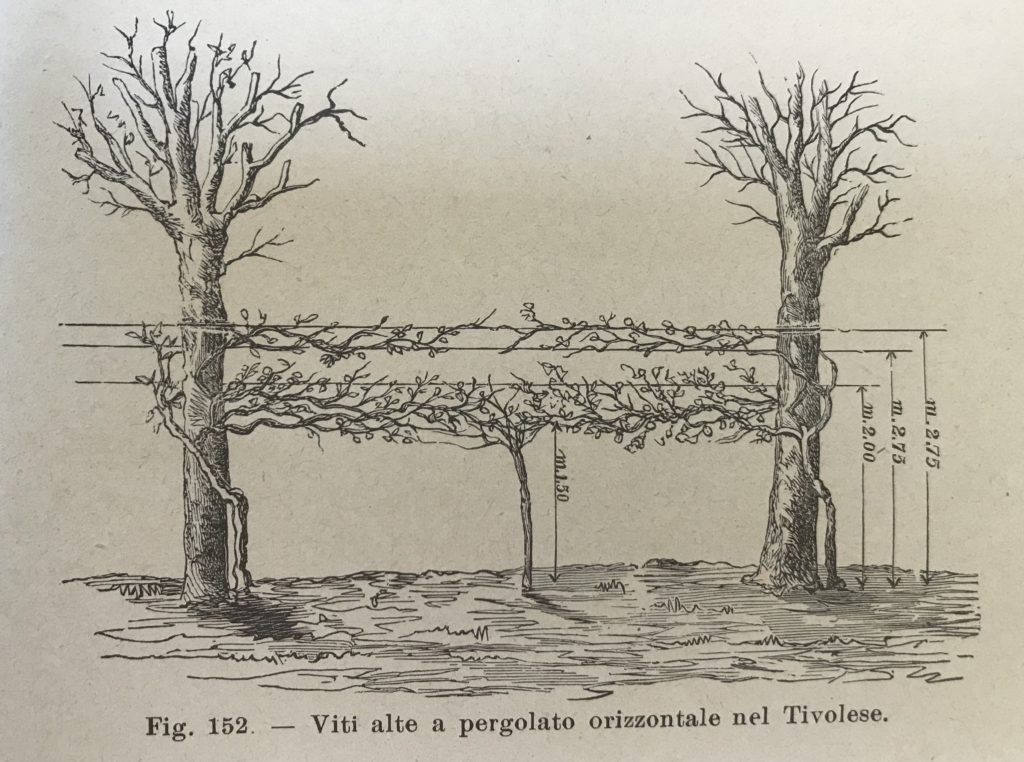

From the nineteenth century, viticulture became a science and many agricultural treaties flourished, that described in detail the traditional Italian systems. For this part, I referred to the works of two outstanding scholars of the nineteenth and twentieth century, Prof. Ottavio Ottavi and Prof. Domizio Cavazza.

The Italian viticulture of the time, in the center-north, had remained based of that of ancient Rome, with the arbustum italicum (alberata) and of the arbustum gallicum (piantata). These two archetypes, however, had given origin to a myriads of different systems, which (the same scholars admit) were difficult to list in all possible variants. Furthermore, there was a lot of confusion in terms at this point. The term "alberata" was used often to indicate one or the other system.

Especially the elm, maple and poplar were still used. Now we can also understand why.

The ideal, as living tutor, is a plant whit small root system and foliage, because they must not interfere with the development of the vine. The perfect tree is the maple (Acer campestris), the favorite for vines since the ancient Etruscans. It is slow to grow, it has few roots that go deep down and do not interfere with those of the vines. The pruning can model easily its small foliage. It also adapts well to poor and shallow soils.

The elm (Ulmus campestris) remains the most used tree in the north. It has a strong radical expansion but is very long-lived, it produces excellent fodder (leaves) and fagots and wood. It adapts more to the fertile and humid soils of the Po Valley.

The poplar (Populus nigra) was used because of its rapid growth and because it produces fodder and wood. It is not so suitable for the vine, because it has an extensive root system and too dense foliage.

The mulberry (Morus alba) was used above all in Veneto even though it was not suitable. It makes too much competition for the vine. However, it is suitable to put together two businesses: the grapes and the silkworm breeding. However, the introduction of copper treatments at the end of the nineteenth century (which kills the bug) made this coexistence very difficult.

In addition, these trees were used too, to a lesser extent: the willow, the manna ash tree, the ash tree, the dogwood, the lime tree, the hornbeam, the oak, the cherry tree, the olive tree, the walnut and the fig tree.

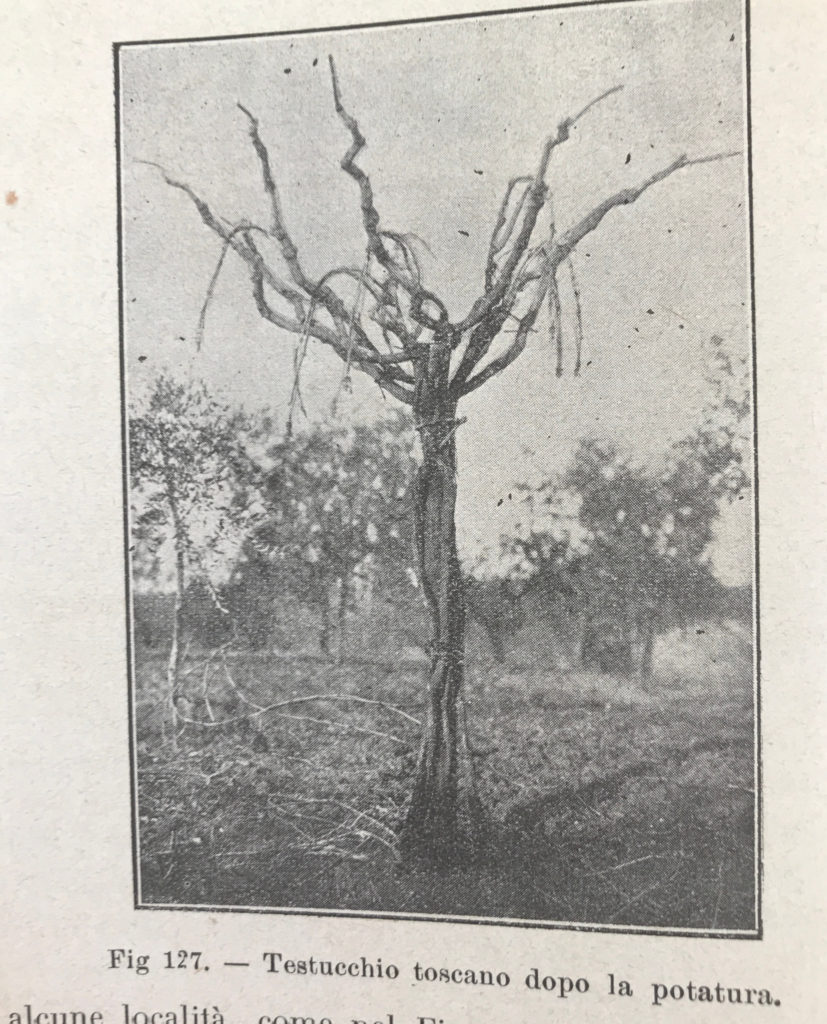

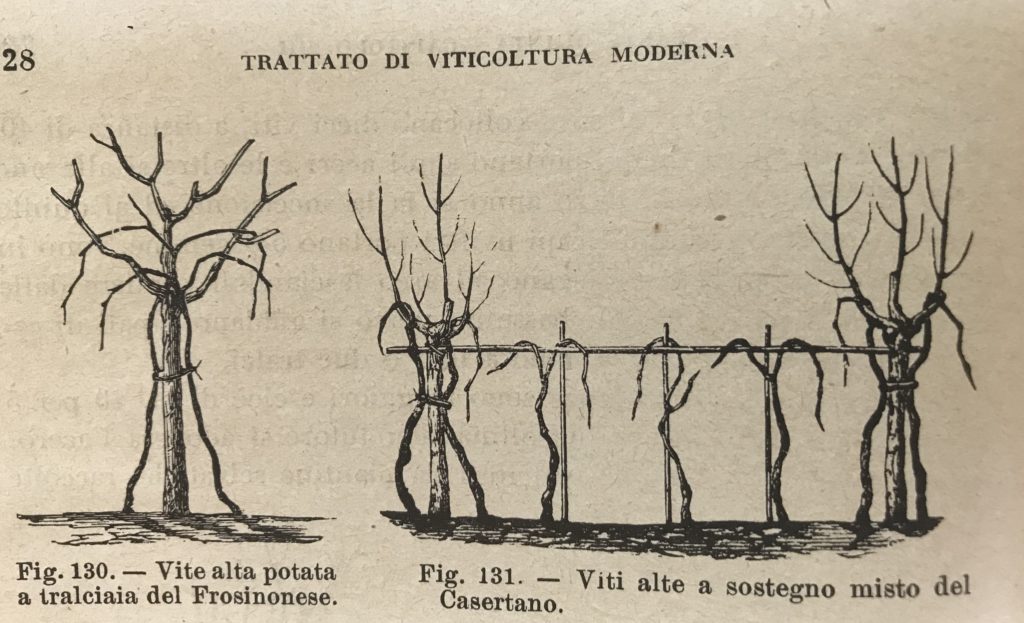

The simplest system, the old arbustum italicum, was called testucchio. It was widespread especially in Tuscany, but also in the Marche and Lazio, with a slightly different planting and pruning methods. Above all, maples were used, called oppi or loppi in Tuscany (acero, in Italian). Among the testucchi, the winegrowers could also grow low vines, resting them on poles, thus forming a complete row. In the Caserta area, there were similar solutions but with high vines.

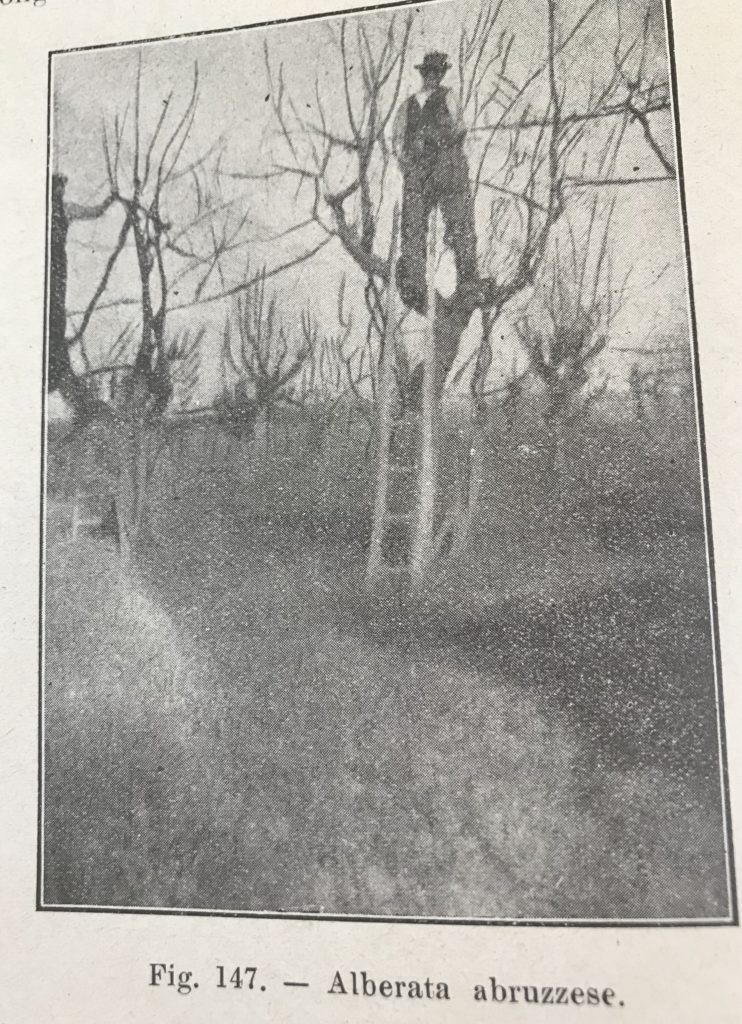

In Abruzzo, the vine-shoots were intertwined to form a large horizontal square, forming the so-called capanne or capannoni.

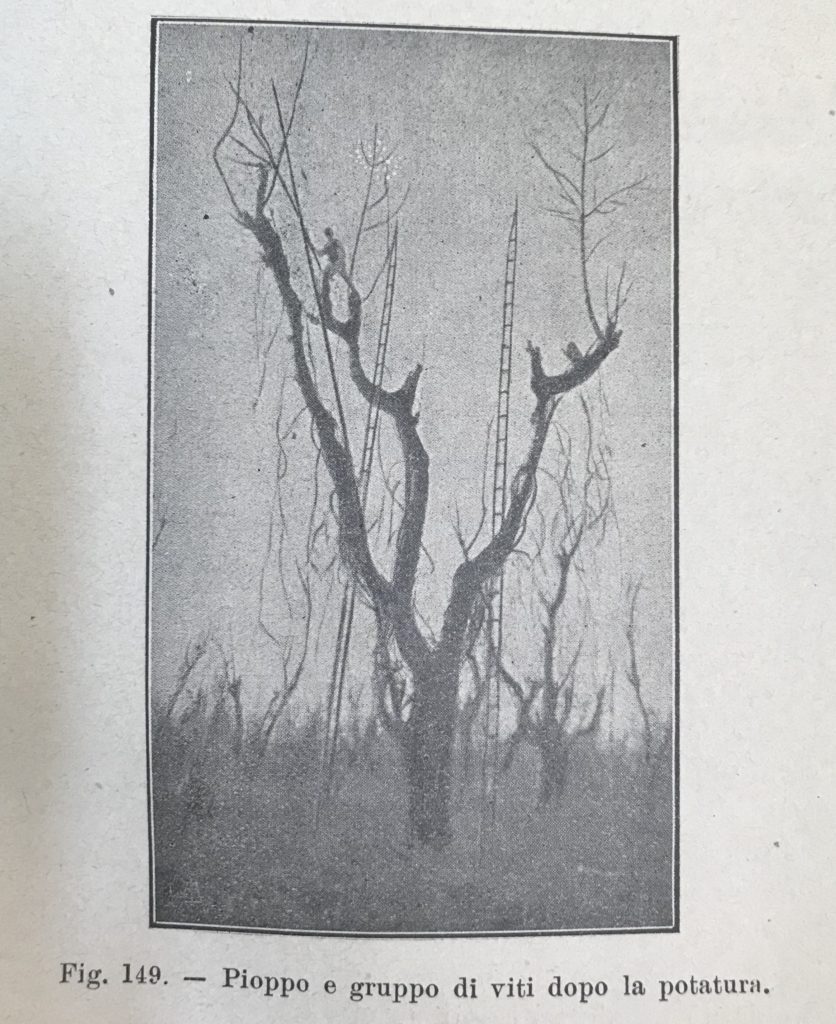

In the area of Aversa (near Naples), the cultivation of Asprinio grapes on poplars reached up to 20 meters in height. Note, in the photo, the size of the man on the tree. In the inter-row, the winegrowers grow other species such as hemp, corn, potato and various cereals.

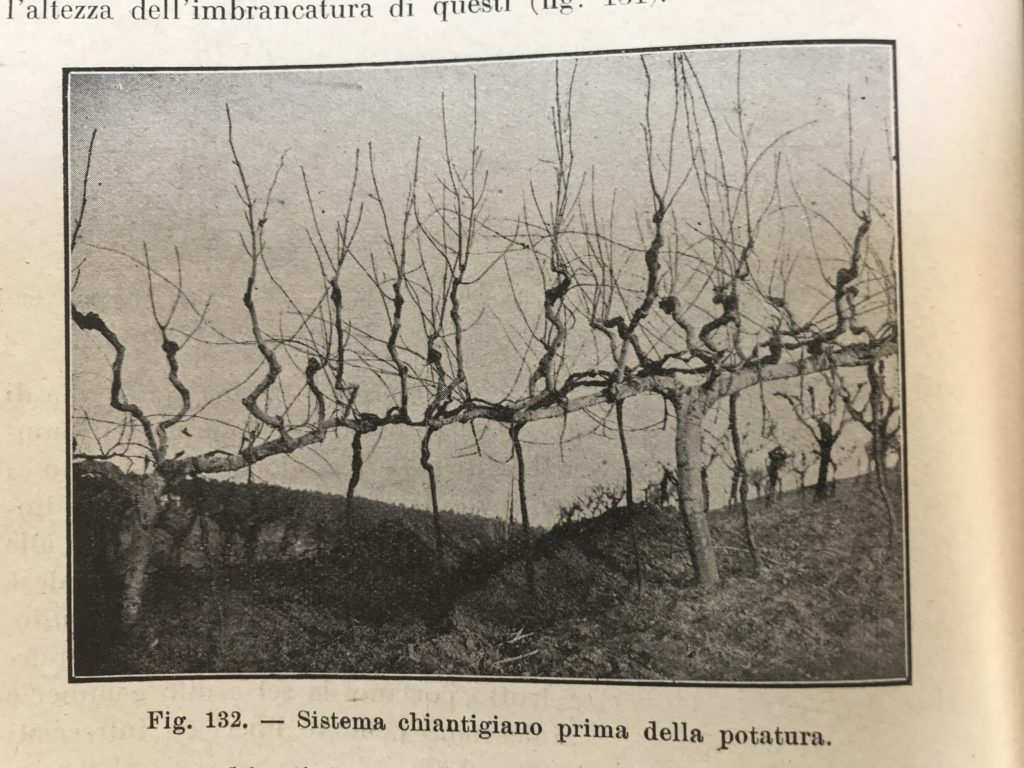

The "Chianti system" was based on the maple trees, whose branches were pruned to stand horizontally and join those of the neighbors, obtaining a sort of continuous espalier on which the vine climbed.

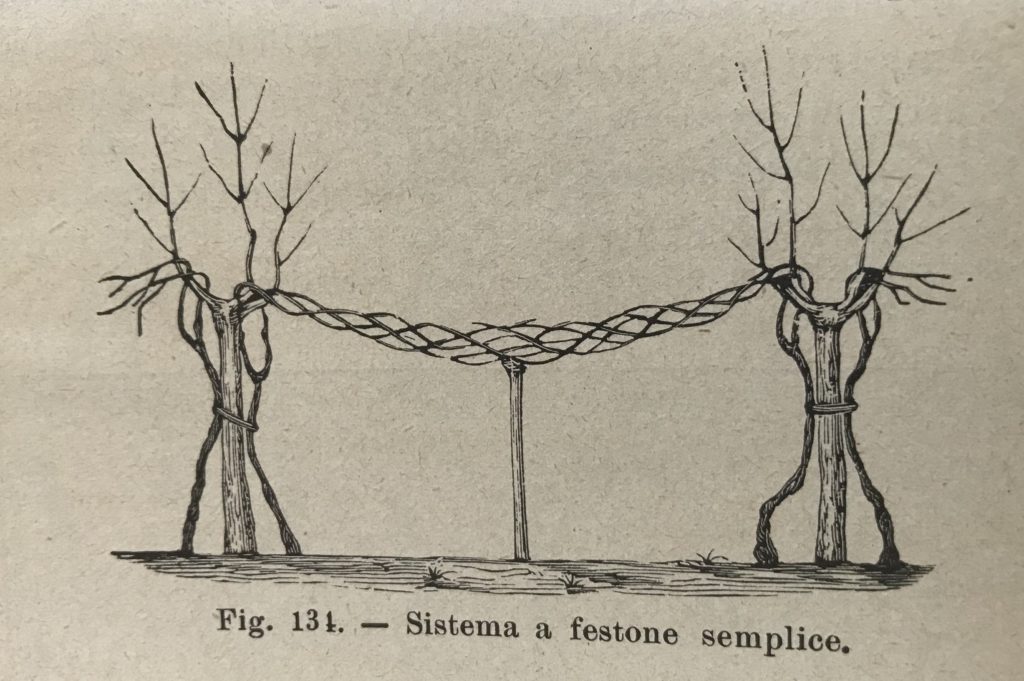

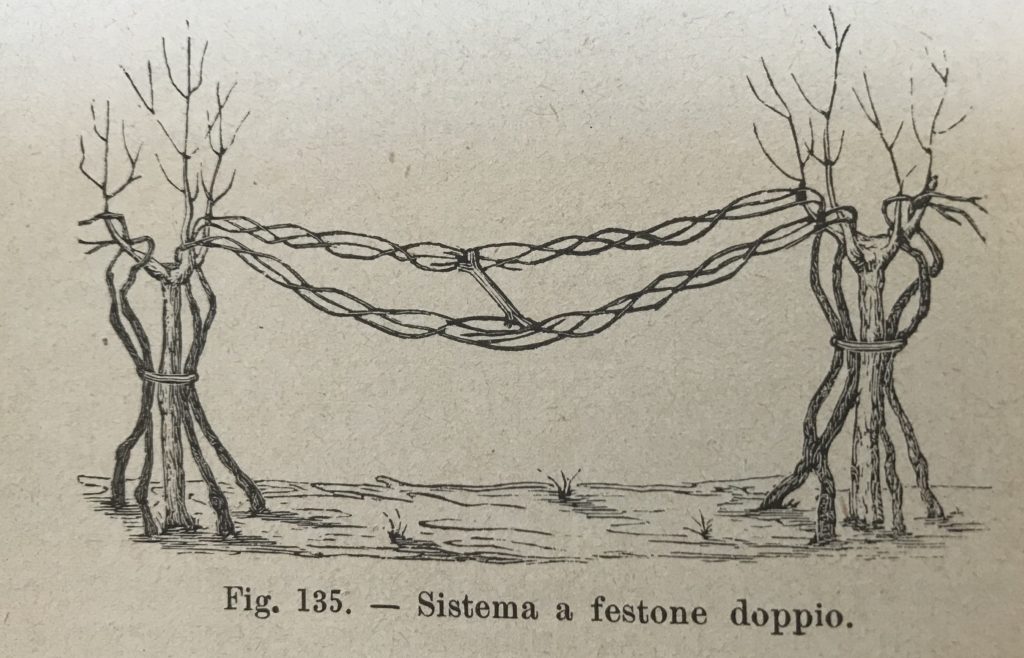

The “festoons system” (or "tralciaia" or "pinzana") was typical of the areas of Pisa (Tuscany), Caserta, Naples and the Emilia. The festoons were formed by very long intertwined vine-shoots. Sometimes they had to be hold up by sticks or separated by a crossbar.

In Emilia it was mainly used the elm, in Romagna the maple, both much lower. In the area of Ferrara, the vines were very high on walnut trees. In these zones, the rows of "married vines" were often on the edge of the fields and along the ditches.

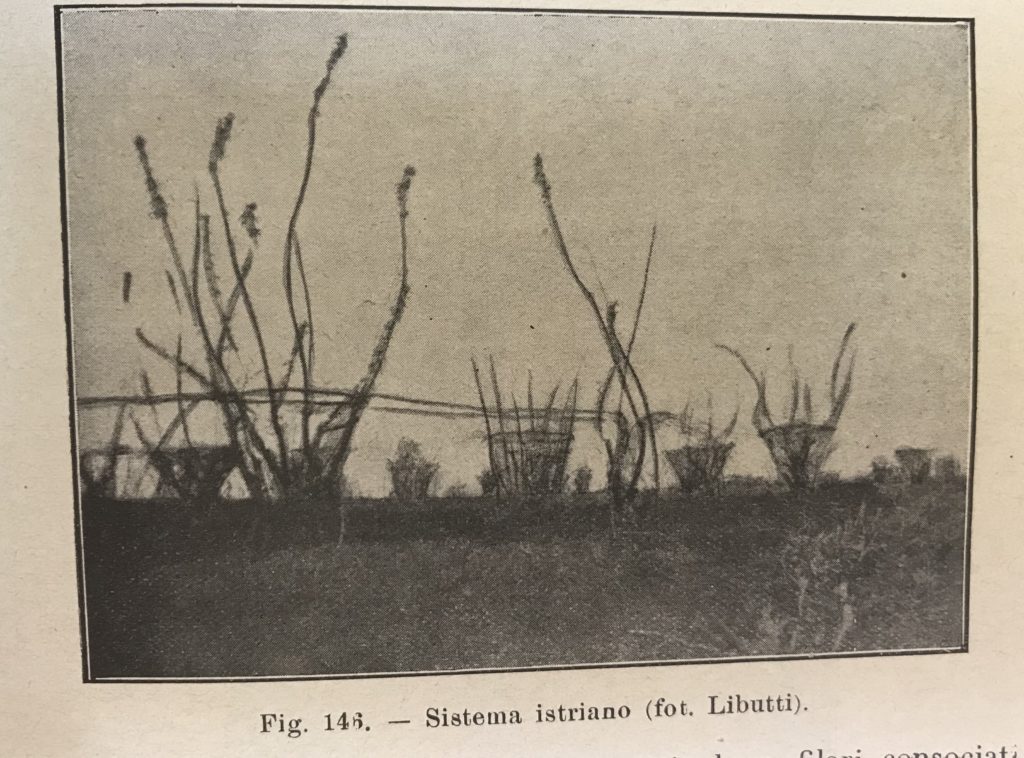

The "Istrian system" was based on low-grown maples or ash trees, like stumps, from which numerous branches spread out, which were joined to form a circle at a certain height. The vine-shoots stretched up to the circle, then spread out and joined the neighboring trees. This system was used for local varieties such as Terrano, Isolana, Nera tenera and Crevatizza. Prof. Ottavi says that this system was disappearing already at its time.

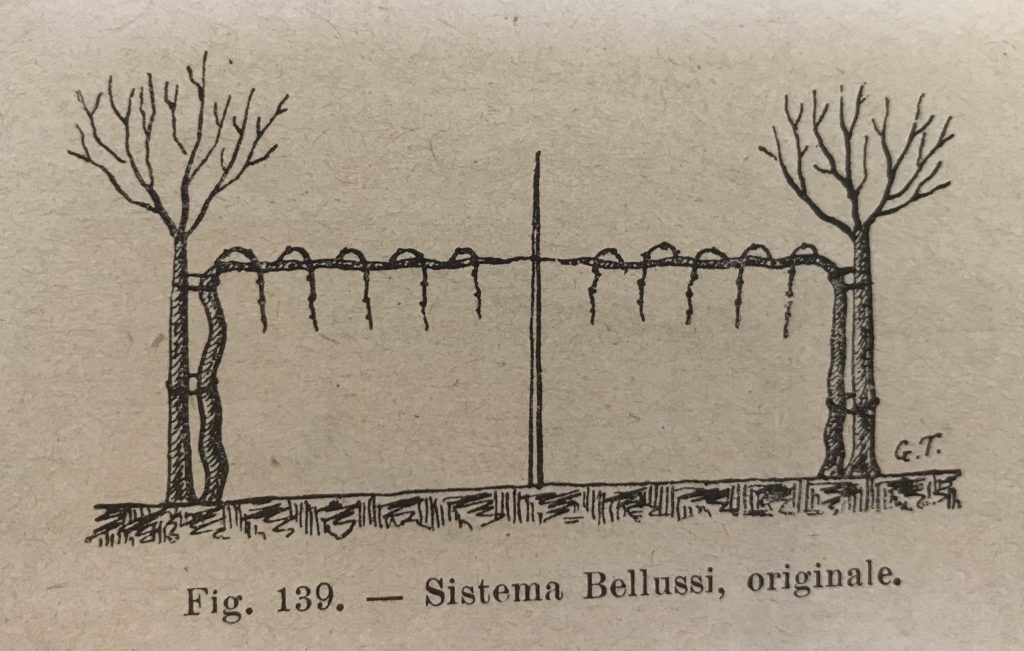

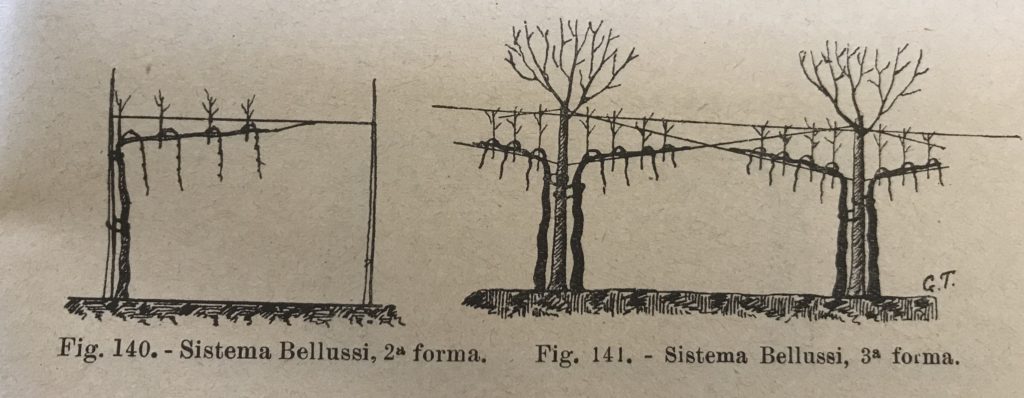

In the nineteenth-twentieth century, some new mixed forms evolved from the more traditional ones, with wires and poles together with trees, to try to modernize this type of vine-training system. An example was the "ray system" or Bellussi (from the name of the inventors). It was widespread especially in Veneto. The ray systems presented numerous variations.

The mixed pergolas consisted of trees with wooden scaffolding and iron wires. They were located in Tivoli area, in Piedmont and in Emilia.

In any case, in the twentieth century this ancient culture has disappeared.

From 1920, a fungus from Asia decimated the elms (the Dutch elm disease, DED, "grafiosi" in Italian).

In '20s, Prof. Cavazza explained that the gradual disappearance of the "married vines" was due above all to changed technical and economic conditions. He lists the disadvantages of this system with respect to the "dead" tutor (a pole): it takes more time to reach normal production, the trees shade the vine, the grapes mature later, there is greater need for fertilizer (both for the vines and the trees), greater difficulty and expense in pruning and all other work (from treatments to harvest).

Yet he had resisted for a long time even for undoubted advantages, listed by Cavazza himself, as the great longevity of the vineyard. In addition, the tutor trees also give useful products to the farm, such as fodder for animals and faggots. The trees partly protect the vines from frost and hail. Among the trees the winegrowers can cultive other crops... It is simple to understand as these advantages belong however to a promiscuous agriculture, to an old rural world that was not able to exist more.

In fact, above all after the Second World War, the Italian viticulture had a profound transformation. The modern production required a highly specialized viticulture. In this new world, there were no place for the "married vine”, survived for over three thousand years.

If you want to see an Etruscan vineyard, you can come to Guado al Melo: we created it with local wild vines. Alternatively, you can still find one of the above systems in Aversa zone or in some small estates of Tuscany and Emilia Romagna.

Italy has certainly sacrificed much of its rural culture to modernity. The important thing is not to lose its memory, because it is part of our history. This is why a “married vine” is on the label of our wine Atis (Bolgheri DOC Superiore).

Not even death

Nella prossima puntata scopriremo invece le varietà ed i vini Etruschi, oltre che le modalità di vinificazione.

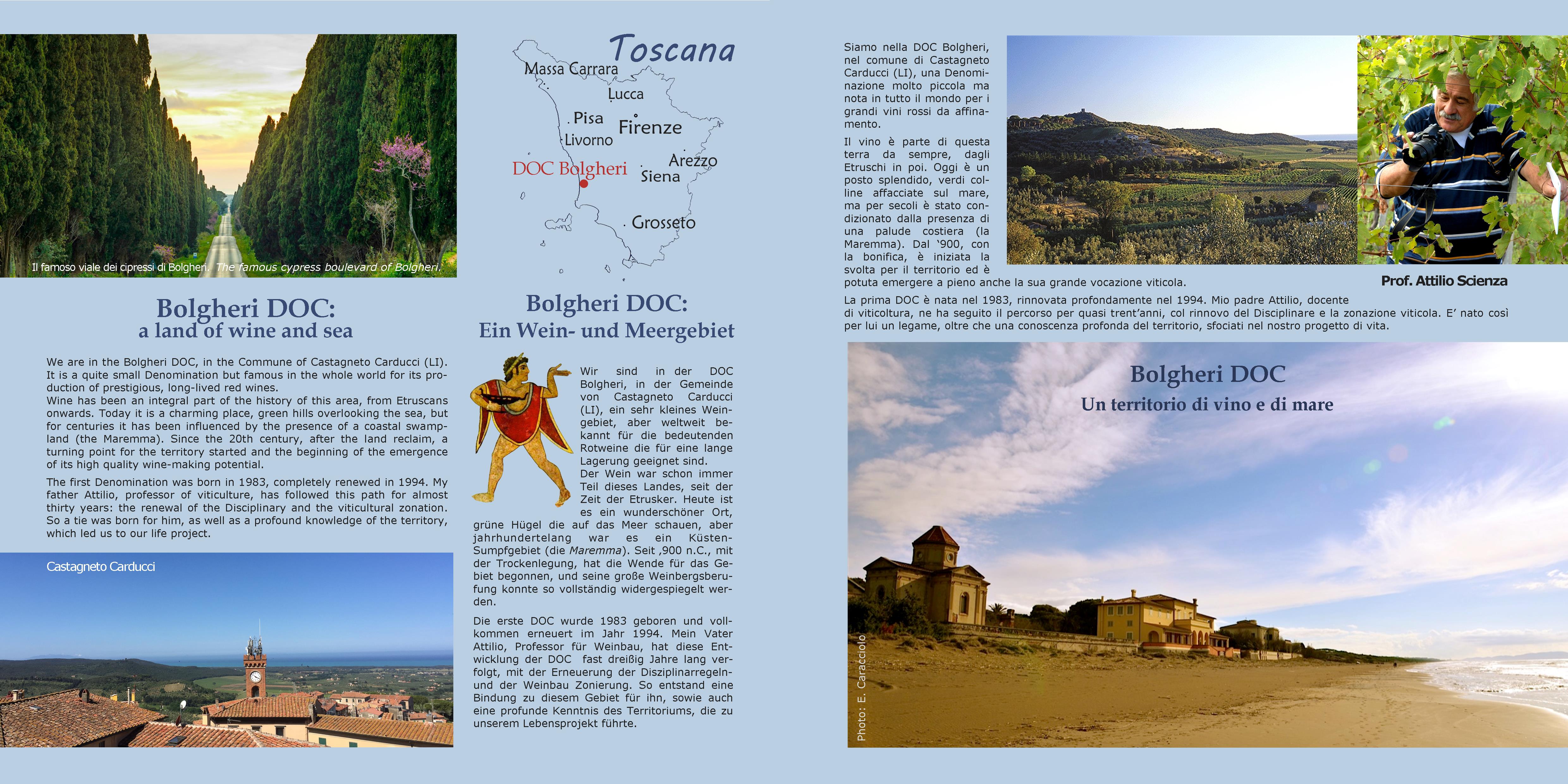

Wine and the Etruscan (I): the first winegrowers

Wine and the Etruscans is a fascinating theme but little known. When people thinks at the antiquity of Italian wine, they thinks almost exclusively to Rome. Obviously Rome has played a fundamental and extraordinary role in the history of wine, but also the Etruscans have been relevant. Above all, they came first and taught so many things to the Romans.

Why do the Etruscans interest we so much?

Because they were the first inhabitants of our lands and were the first winegrowers in Italy. Millennia ago, therefore, he was here in our place, doing our own work!

But who were the Etruscans? Read below ... if you already know this part, skip it.

After a territorial decription, we will dedicate ourselves specifically to wine.

“... Etruria was so powerful that the fame of it filled not only the land, but the sea as well, and through all of Italy, from the Alps to the Strait of Sicily. “

Livy, Ab Urbe Condita, book I, I c. b.C.

Our territory was characterized by a row of hills parallel to the sea, in the middle of a marshy flat area (the North Maremma), inhospitable and where proliferated malaria. Since prehistoric times the people lived in the hills practicing hunting and gathering wild products. Later, the first permanent settlements arose and thence the first early agricultural societies that gave origin to the Etruscan civilisation.

The great territory wealth was the big mining resources (above all iron), which exploitation initiated from the Bronze Age (12th century BC). In contrast to the large-scale inurbations in southern Etruria, few cities rose in this area, and the populations remained scattered. Three great city-states dominated the coastal area: Pisa, which controlled the northernmost stretches; Volterra dominating the Cecina Valley to the sea; and Populonia in the south. The Etruscans, excellent hydraulic engineers, reclaimed part of marshy plains near the sea, and used it for agriculture.

Our territory, Castagneto Carducci e Bolgheri, was part of city-state of Populonia. Its ancient remains are at few Km from our winery, seaward the charming Gulf of Baratti.

Populonia declined on the Roman period.

decadde come città già in epoca romana. Claudius Rutilius Namatianus, on V c. A.C., passing along the coast with his boat, saw only ruins:

Close at hand Populonia opens up her safe coast,

where she draws her natural bay well inland...

The memorials of an earlier age cannot be recognised:

devouring time has wasted its mighty battlements away.

Traces only remain now that the walls are lost:

under a wide stretch of rubble lie the buried homes.

Let us not chafe that human frames dissolve:

from precedents we discern that towns can die.

Claudius Rutilius Namatianus, 417 AC

De Reditu Suo (About his return), I, 401-414

The most important Etruscan site in Castagneto is the Tower of Donoratico, unfortunately not visited because it is located in a private property.

So, the Etruscans played a decisive role in the spread of the wine culture in the western world.

They were the first to develop viticulture in Italy introducing their practices into much of the peninsula, from the north (Emilia Romagna) to the south (Campania), Rome included. Great navigators and traders, they came into contact with the cultures of the eastern Mediterranean and introduced in the West cultural aspects of wine, as the religious symbolism and ritual consumption in the symposia. They brougth from East also the oriental grape varieties. Finally, they also spread wine and its culture via commercial channels to the people of western Europe who were still ignorant of this beverage, such as the Celts, the German tribes, and the Iberian peoples.

However, we will go into more detail in the next post.

RECOMMENDED TO VISIT

Parco Archeologico di Baratti e Populonia, loc. Baratti, Piombino.

Collezione Gasparri, Via di Sotto 8, Populonia Alta.

Museo Archeologico del Territorio di Populonia p.za Cittadella 8, Piombino.

Parco Archo-minerario di San Silvestro, via di Sa Vincenzo Sud 34/b, Campiglia M.ma.

Museo del Palazzo Pretorio, via Cavour, Campiglia M.ma.

Museo Archeologico di Cecina, Villa Guerrazzi loc. La Cinquantina, San Pietro in Palazzi.

Museo Civico Archeologico di Rosignano M.mo, Palazzo Bombardieri, va del Castello 24.

Area Archeologica di San Gaetano a Vada.

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Castiglioncello, via del Museo 8, Castiglioncello.

Museo Etrusco Guarnacci, Via Don Giovanni Minzoni 15, Volterra.

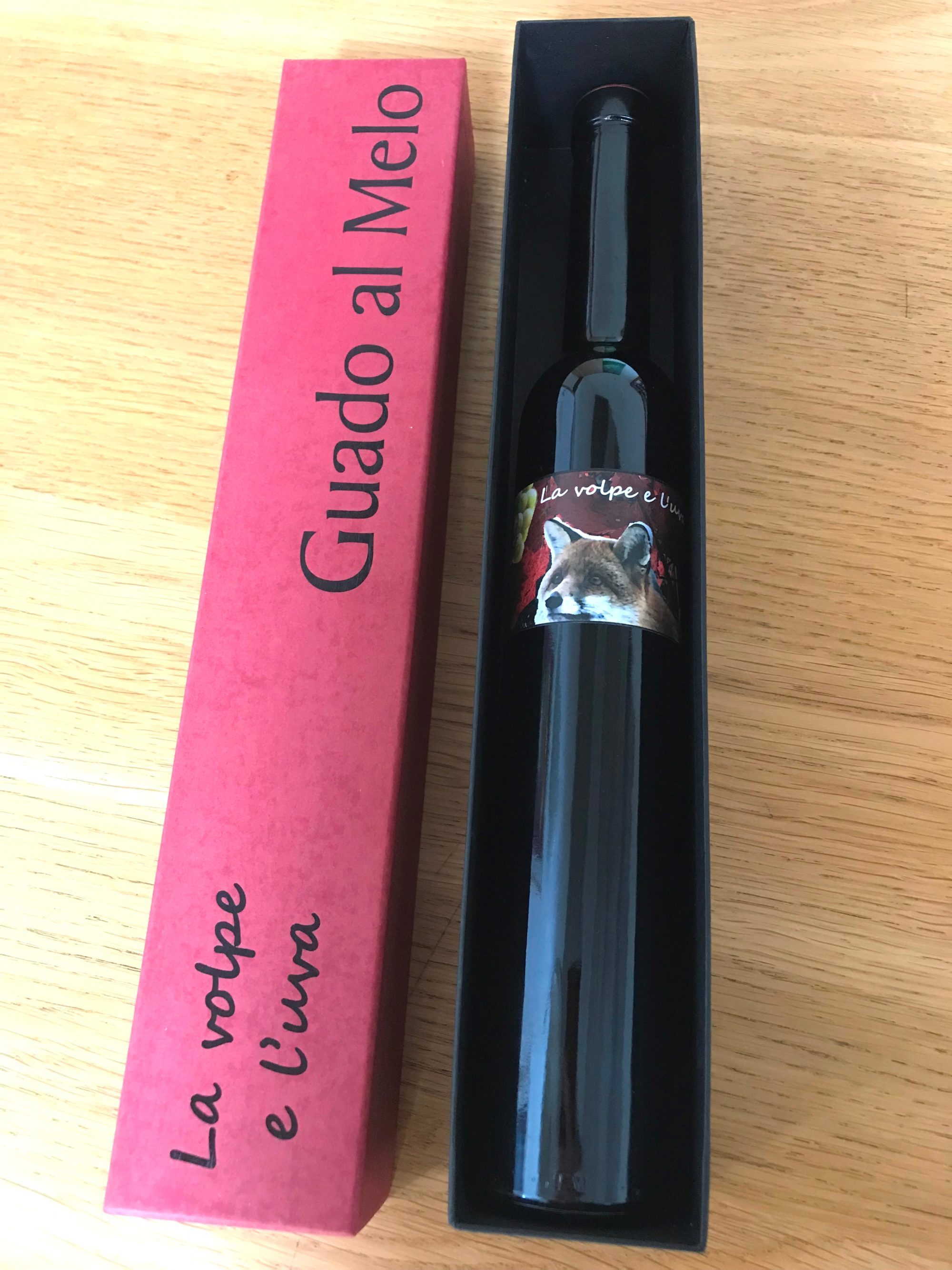

Raisin wine, Malvasia grapes based, "La volpe e l'uva": natural sweetness

I'm presenting you a new wine, a very little production that we made to have a excellent raisin wine but not too sweet.

I often dislike sweet wines because they are "heavy", quite nauseous. So, Michele and I decided to produce a perfumed and full-body wine, but with a moderate sweetness.

Its aromas are fantastic: white flowers, apricot, cinnamon, aromatic herbs, orange zest, raisin grapes... In mouth, it is full, with a pleasant sweetness. It is very good as aperitif or after-dinner. It is also optimal in pairing with mature or blue cheeses or fois-gras... It is also good pairing with not too sweet desserts, for exemple with desserts with nuts or chocolate.

Why the name "La volpe e l'Uva" (The fox and the grapes)?

Do you remember the famous fable of Phaedrus " The Fox and the Grapes " ? In the summer nights we often see foxes in our vineyard. However, rather than on the moral end of the fable, we focus on the eager gaze of the fox, the intense desire for that perfect fruit, unique and precious (as this wine). I made the label thinking to this idea: a great desire that we want to satisfy. The bicolor box is very beautyfull.

Why "natural sweetness"?

Because this wine is produced in artisanl way, without added sugars. Michele made it with an ancient and traditional method, called "mistella". A little portion of the grapes are picked-up and dried on trellis in a cool and airy place. Then they get pressed in a wooden manual press, and added to the must in fermentation of the fresh grapes. The addition of this concentrate juice causes the arrest of the process, leaving a natural sugar residue. It was aged for 4 years in oak not-new barrels.

Malvasia is a traditional grapes, often used in Italy to produce sweet wines. We have few plants of Malvasia, so we produced only 593 bottles.

A network for "conscious travelers", to discover the cultural identity of a territory

In winter a project was presented us, aimed at creating a tourism brand, focused on enhancing the culture of the territory. Those who know us (or know Guado al Melo) certainly know that it seemed made for us!

We compiled the membership form and now we have the news that we have been selected to be part of the pilot project!

Here is a summary of what it is:

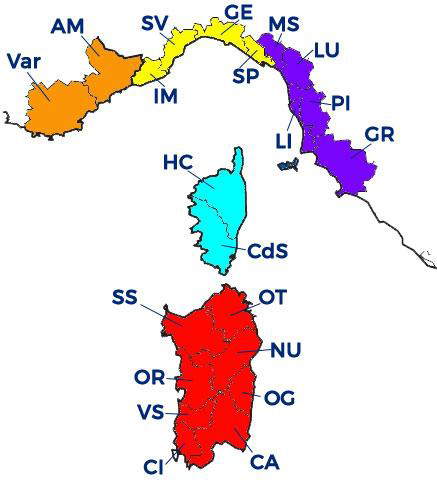

WHERE. The project is centered on a strip of Mediterranean Europe, joined by similar natural environments and cultural continuity: the Italian coastal strip of Tuscany, Liguria and Sardinia, the French Mediterranean coast and Corsica.

WHERE. The project is centered on a strip of Mediterranean Europe, joined by similar natural environments and cultural continuity: the Italian coastal strip of Tuscany, Liguria and Sardinia, the French Mediterranean coast and Corsica.

WHAT. The project aims to give birth to a network of small local businesses, accumulated by deep territorial and cultural roots. The idea is to present a particular path to "conscious travelers", ie people looking for non-trivial tourist experiences, eager to meet local realities capable of deepening the narration of their territories, savoring real and unique experiences. The network integrates places of memory and nature (such as museums, cities of art, parks) but also places of the human present, represented by itineraries of taste, typical and artisanal productions.

SUSTAINABILITY. The realities that become part of the project must respond to the fundamental principles of cultural, environmental and social sustainability.

THE PROJECT. For now we are still at the beginning. Among the many candidates, 80 (of the territories indicated) were selected , chosen for their particular correspondence to the spirit and purpose of the project. These pilot companies, including us, will now be accompanied in a certification process and (if necessary) adaptation to all the required standards. After that the project can be opened to other realities and, at the same time, promoted to the public.

The project is called S.MAR.T.I.C., acronym of «Sviluppo Marchio Territoriale Identità Culturale», "Development of Territorial Cultural Identity Brand". It is co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund from the INTERREG Italy-France Maritime Program 2014-2020. http://interreg-maritime.eu/it/web/s.mar.t.i.c./progetto

The reference for the territory of Livorno is the cooperative "Itinera Progetti e Ricerche" gbenucci@itinera.info +39 0586 894563 www.itinera.info/blog/

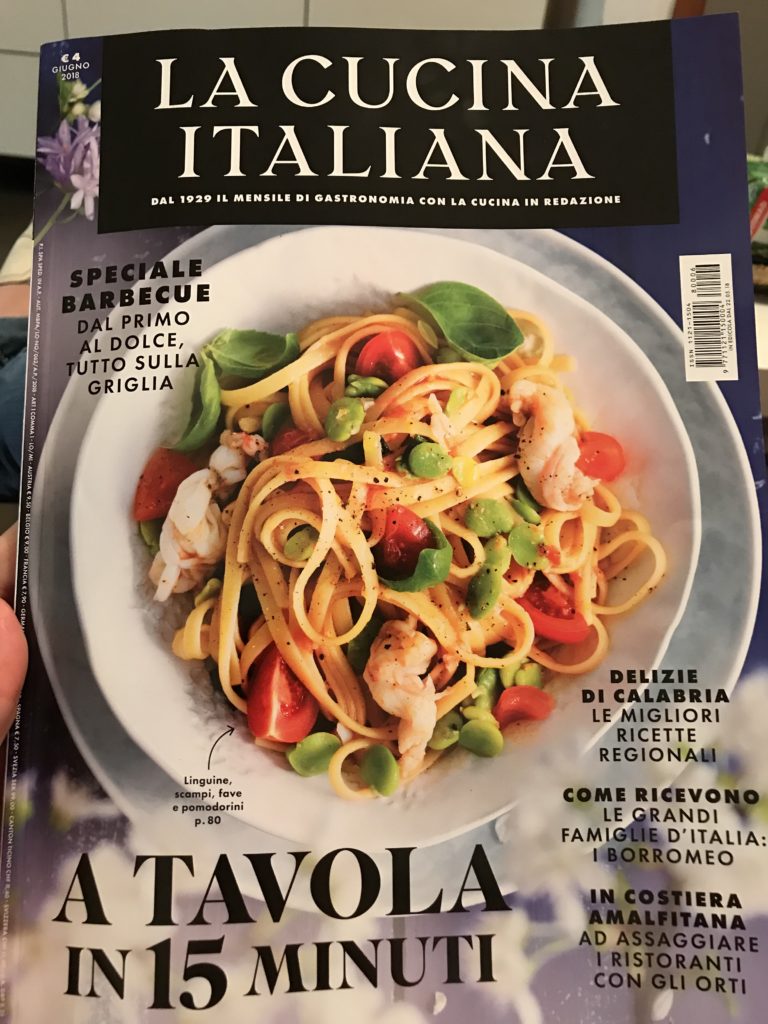

Criseo wine conquers all: even "La Cucina Italiana" magazine recommends Criseo 2016

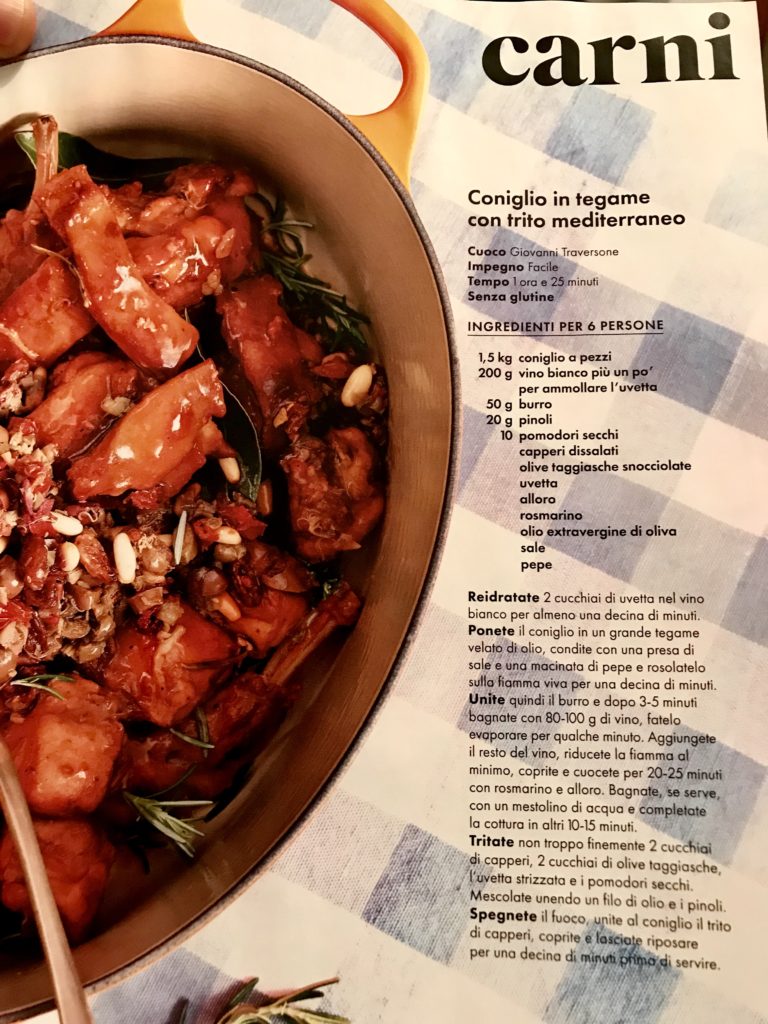

Mediterranean rabbit:

1,5 Kg rabbit

200 g white wine, other for raisins

50 g butter

20 g pine nuts

10 dried tomatoes

Desalted capers

Taggiasca olives

Raisin

Laurel

Rosemary

Extravirgin olive oil

Salt and pepper

Soak 2 tablespoons of raisins in white wine for 10 minutes.

Brown the rabbit pieces for about 10 minutes in a large pan with a little oil, salt and pepper. Add the butter and, after 3-5 minutes, 80-100 g of white wine, and after 2-3 minutes the rest of wine.

Then lower the heat to a minimum, add laurel and rosmary, close the lid and cook for about 20-25 minutes. Then add a little water (if necessary) and cook again for 10-15 min.

Meanwhile coarsely chopped 2 tablespoons of desalted capers, 2 tablespoons of pitted olives, the dried tomatoes, and the squeezed raisins. Add a little oil and the pine nuts to the mixture.

At the end of cooking, add the Mediterranean mixture to the rabbit, stir, close and let it rest for about 10 minutes.

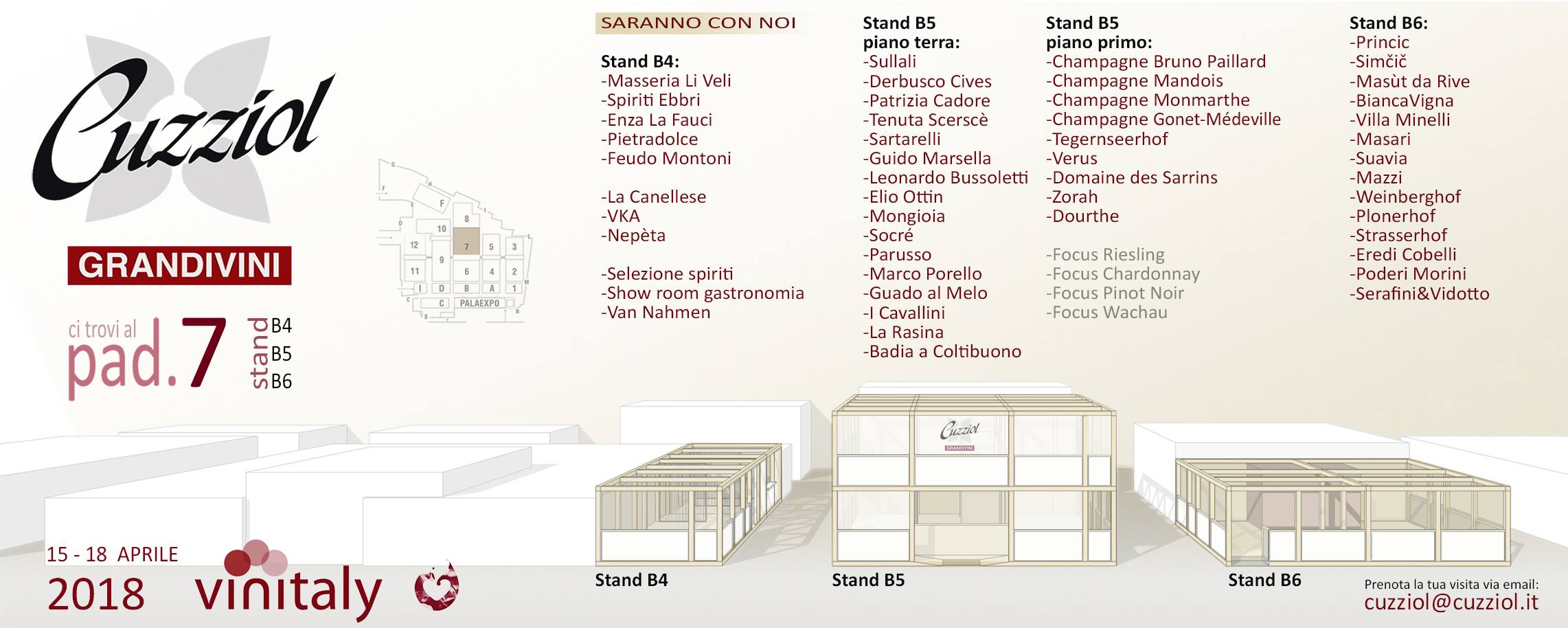

Are you ready for Vinitaly?

We are ready! We will be at Pav. 7, stand B5, c/o our distributor for Italy CuzziolGrandiVini. We'll wait for you at our table, Michele Scienza and Annalisa Motta, as usual.

Thre will be the current vintages of our wine, plus these news:

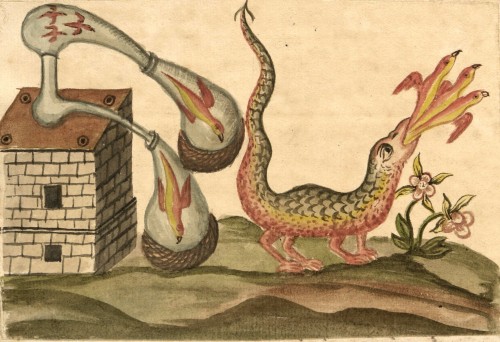

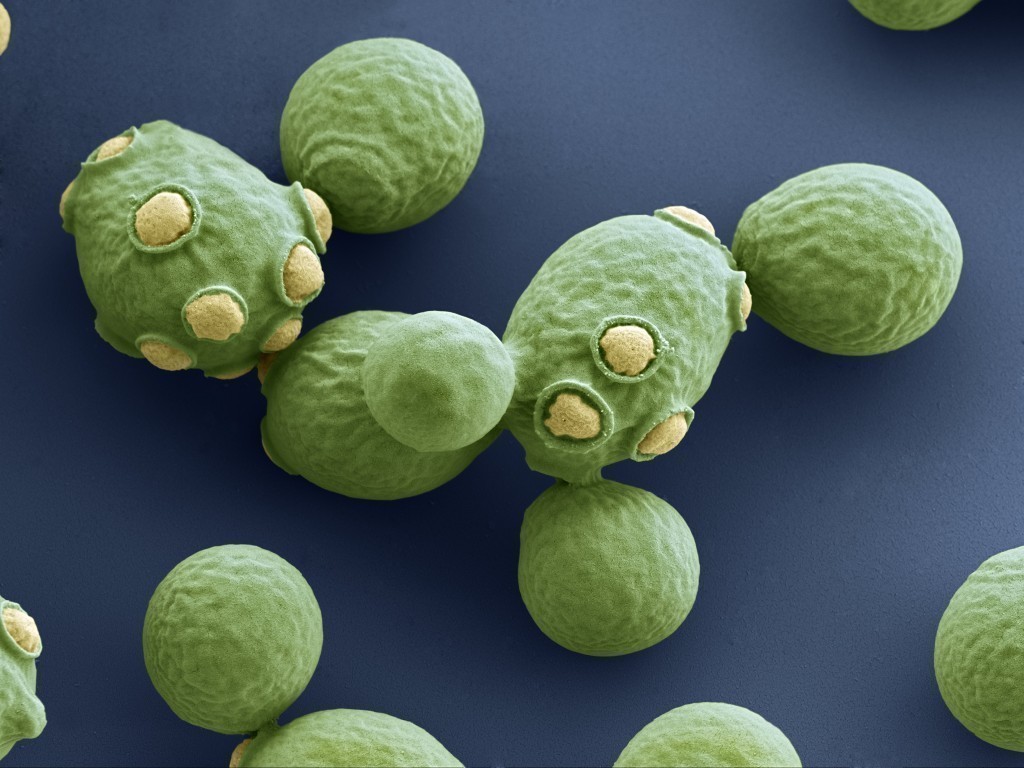

Fermentation in history 2: “It is rarefied to Spirit”

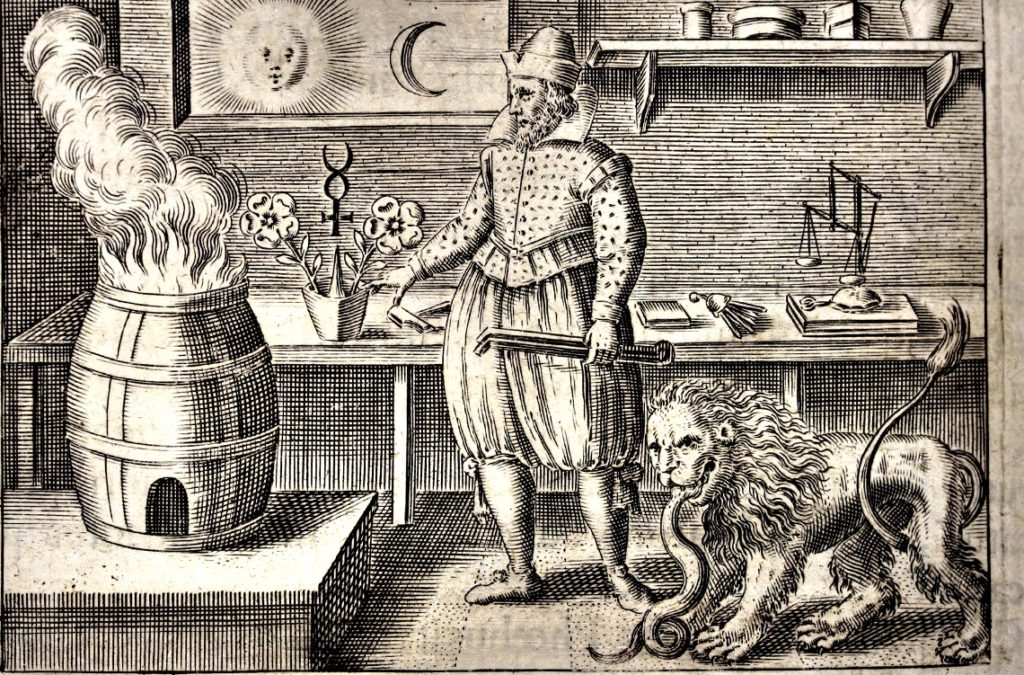

First interpretations on the fermentation process itself appear only in the era of alchemists-scientists, the seventeenth century. It is the historical moment in which the investigation of the world becomes more profound, though still mixing irrational aspects with burning science.

The understanding of this process began with the observation that a substance is formed by fermentation: alcohol (even if it was not called that at the time). The identification of this substance has its roots in distillation and alchemy.

The oldest stills date back to the 2nd century BC, found in Mesopotamia and in Egypt. In ancient times they were used only to produce essences for perfumed balms or for medical purposes. The distillation of alcohol, to produce hydroalcoholic solutions, probably began with the Arab alchemists Rhazes (Abū Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariyyā al-Rāzī) and Avicenna (Ibn Sīnā) between the 10th and 11th centuries. This knowledge was collected and disseminated in the West especially by the Schola Medica Salernitana, from the tenth century onwards.

In the thirteenth century the German philosopher and bishop Albertus Magnus describes in his works the substance "aqua ardens" obtained from the distillation of wine, so light to float on oil. Aqua ardens, burning water, and spirit of wine are among the most used terms for centuries to indicate alcohol or a more or less concentrated hydroalcoholic solution. Spirit derives from the Latin "spiritus" which means breath, vital spirit and, by extension, exhalation. The word alcohol will come later. Alcoholic beverages were indicated in this period with the generic term of aqua vitae (water of life), whatever the starting material.

The first work that describes in detail how to produce aqua vitae (with a double fermentation system) is a part of the Vatican code Consilia (1276). It is by the Florentine doctor Taddeo Alderotti, one of the most famous of his time, also mentioned in Paradise by Dante (12:82-85). I

Initially distillation of aqua vitae was carried out only in monasteries but, within a century, became increasingly popular. It was widespread mainly thanks to the treaty of the Paduan doctor Giovanni Michele Savonarola (1385-1468), the "De conficienda Aqua Vitae", which explained how to prepare it (he is the grandfather of the famous Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola).

Then by empirical distillation practice, increasingly perfected, it was born the identification of the substance that characterizes the wine from the grape-juice. Based on this knowledge, in the seventeenth century, we find the first attempts to interpret fermentation.

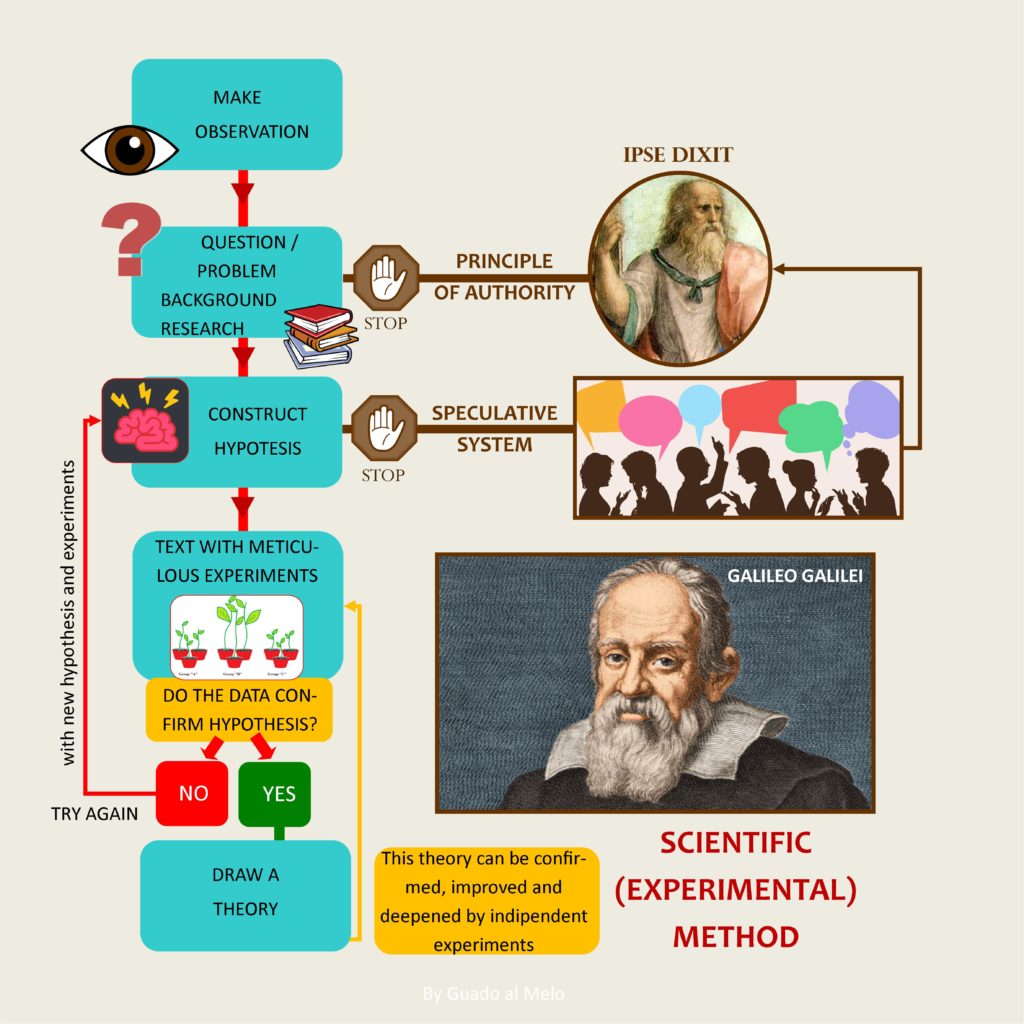

The seventeenth century is an era that represents a important break in the history of humanity and science, thanks to the birth of the experimental method. This will allow to overcome the principle of authority over time and to abandon gradually the mystical and magical aspects of alchemy.

Naturally it was not a clean break. For a few more centuries science remained in a middle world, poised between rationality and magical thought, with different figures of cutting-edge scientists and many still linked to the past. Even those scientists, which we remember today for important discoveries, still maintained (to a greater or lesser extent) some magical or irrational aspects.

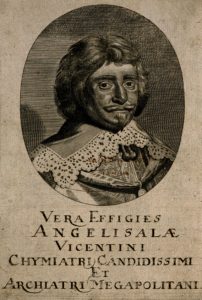

Returning to our topic, at the end of the sixteenth century the physician and chemist Angelo Sala (1576 - 1637) made the first studies on the formation of alcohol from fermenting musts.

Shortly afterwards the Flemish doctor and philosopher Johannes Baptiste van Helmont (1580-1644), disciple (and critic) of Paracelsus, admirer of the new experimental method, was among the first to hypothesize that fermentation was a chemical process, mediated by not well specified intermediaries. For van Helmont (and others of his time) reality consists of "minima naturalia", very small elements, corpuscles at the base of all matter. Chemical reactions, which he call indistinctly "fermentations" or "effervescences", are additions or subtractions of these particles. At the basis of the reactions there is a spiritual principle that operates through "ferments", unidentified mediators.

In addition to this, van Helmont identified that the gas released during fermentation is the same that is obtained by burning coal, at the time called “gas silvestre”, sylvan gas (because it derives from the combustion of plant matter). Today we call it carbon dioxide.

Another exponent of this world in the balance between nascent science and alchemy is Nicolas Lémery (1645-1715), French chemist who, in the second half of the seventeenth century, considered five substances at the base of nature: Water, Spirit, Oil, Salt and Earth. His work "Course of Chemistry" (1687) was a great success and was long considered a reference text. we can find in it a detailed explanation of the process of alcoholic fermentation.

According to Lémey, vinification consists in the transformation of a part of the must (Oil) into alcohol (Spirit), thanks to an action of "rarefaction" by the Acid Salts.

For Oil he means the part that remains non-distillable, while the Spirit is the part that can be distilled and flammable. For Salts he means both those that remain encrusted on the walls of the barrels (tartaric acid) and those that precipitate on the bottom at the end of the vinification.

Lémery, with his language (sometimes obscure for us), begins to identify different elements present in the juice and in the wine, even if with wrong roles in fermentation. This explanation, however, will remain for a long time as a model. In fact we find it (much the same) in the "Dictionary of Chemistry" by Pierre Joseph Macquer of 1766.

In addition to this, however, he reasons that wine no longer has the sweet taste of juice. Furthermore, he says, fermentation takes place more easily and produces more spirit substance if grapes are ripe. The unripe and ripe grapes change in flavor: the first is more acidic and not sweet at all, the other is very sugary. Therefore he concludes that the ripening of grapes (and other fruit) consists in the accumulation of sugars, which become dominant. From here he deduces that the material that undergoes alcoholic fermentation is precisely sugar.

Macquer continues by explaining some traditional practices to increase the sugar in the grapes by concentrating them by drying. He also mentions the practice of adding sugar directly to the must. He also points out that as early as the beginning of the century the Dutch doctor Herman Boerhaave (1668-1738) indicated that sugar is an effective means of promoting fermentation. The practice of sugaring was then widespread among the French wine producers in the early decades of the nineteenth century, thanks above all to the chemist Jean-Antoine Chaptal (wine sugaring in French is called "chaptalisation").

He writes, however, why it happen is still unknown and not easy to discover.

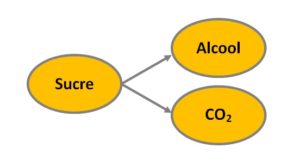

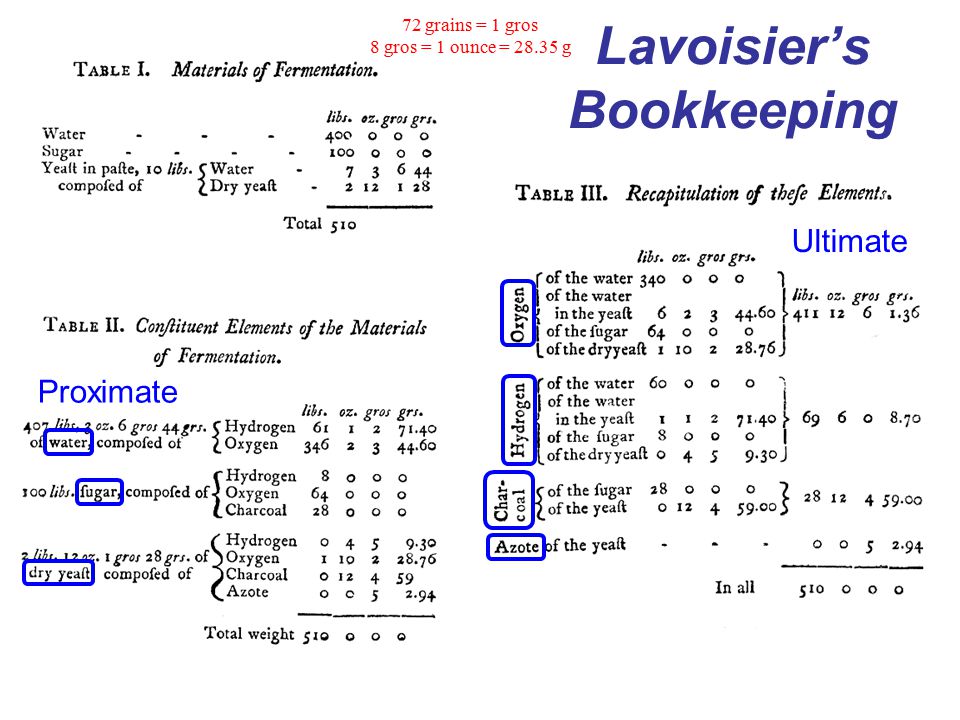

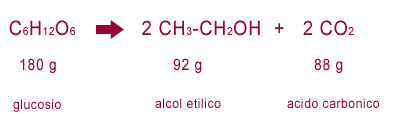

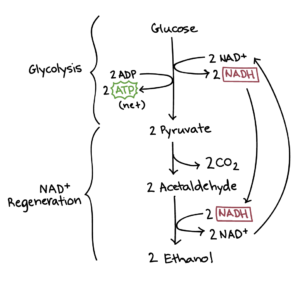

The first to describe clearly what happens during fermentation was Antoine-Laurent de Lavoiser (1743-1794) in his “Elementary chemistry treatise" of 1789. Lavoisier is one of those figures who changed history. He is recognized as the "father of modern chemistry" who, thanks to him, completely detached himself from alchemy.

Lavoisier begins to use the word alcohol and no more spirit of wine. In fact, he thought this term was not adequate because this substance could be formed not only from wine, but also from cider or sugar.

The word alcohol comes from the Arabic al-ko-ol. Originally it referred to the fine and black powder that women used to make up their eyes. From here, in Arabian alchemy, it was used to refer to any very fine powdered compound and so it also passed into the Western Middle Ages. It was then used to indicate the purest essence of a substance. It seems that the first to use the word alcohol in the modern sense was Paracelsus (Theopharst Bombast von Hohenheim, 1493-1541), the best known alchemist of his time. Lavoisier introduced it, however, into the common scientific use. In fact he is also remembered for his important reform of the nomenclature of chemical substances, at the base of the modern one. He wanted to go from the obscure and vague terms of alchemical origin to others, more concise and rational ones.

Returning to fermentation, Lavoiser, based on the knowledge accumulated up to his time, described it roughly as:

grape juice = carbonic acid (carbon dioxide) + alcohol

He experimentally reproduced the process with sugar dissolved in lukewarm water, to then estimate in a very precise way the quantities of fermented substances and the products obtained, also determining their composition. He was the first to write a chemical reaction as an equation. The measures were not exactly precise (given also the limits of the instruments of the time) but it was a real revolution for chemistry.

He described how the sugar split into two parts, and that the fermentation consisted in the oxygenation of one of them, with the formation of a combustible substance, alcohol. He showed that the transformation was not quantitatively exact because other secondary products are also formed.

The formula of the reaction was then defined quantitatively more precisely in 1810 by the French chemist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (1778-1850), thanks to the further improvement of the measuring instruments.

Then the chemists more and more refined the knowledge on the reaction, coming to define it with extreme precision. Today it is schematized as follows.

To get to this formula, however, still lacks a fundamental passage: at the time of Lavoisier there wasn't still organic chemistry!

In fact, nobody has yet respond to that fundamental question that we have taken with us on this journey through the centuries: who does it and why?

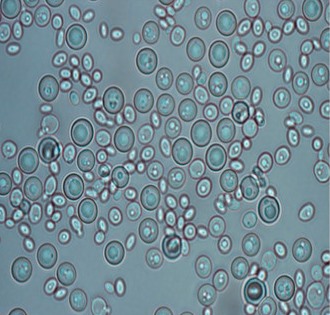

This question also arose spontaneously by Vincenzo Dandolo, an Italian (contemporary) translator of the works of Lavoisier who, in addition to translating, also made numerous annotations to the text. Lavoisier in fact, describing his experiments, tells about using brewer's yeast. Dandolo notes that the latter is formed by the sediment of the beer. He says that the fermentation is not well determined. He asks "why, how does brewer's yeast work? ... So the yeast becomes essential substance to make a complete fermentation, but though there are water, heat and sugar ".

So was yeast already known? No, this term is used to indicate something to facilitate fermentation empirically . Even from the ancient times, it was seen that by adding sediments of fermentation (or a bit of leavened bread dough in the case of bread making) the process started with greater ease. However, at the end of the eighteenth century, although having generally defined what happens, there was still no idea why.

Dandolo asks again: "What fermenting principle introduces this substance, or any other suitable to promote this first notable alteration ...? Would this phenomenon refer to the nitrogen that the yeast  contains? If so, how does nitrogen work? "

contains? If so, how does nitrogen work? "

He says that the yeasts traditionally used are of two species:

- "highly putrescible bodies containing nitrogen" (he write how some facilitate fermentation by throwing pieces of meat into the vat; he also tells how the Chinese add excrement to stimulate the fermentation of a decoction of oats and barley .

- "Bodies that contain a lot of oxygen like acids, neutral salts, clay, metal oxides, etc."

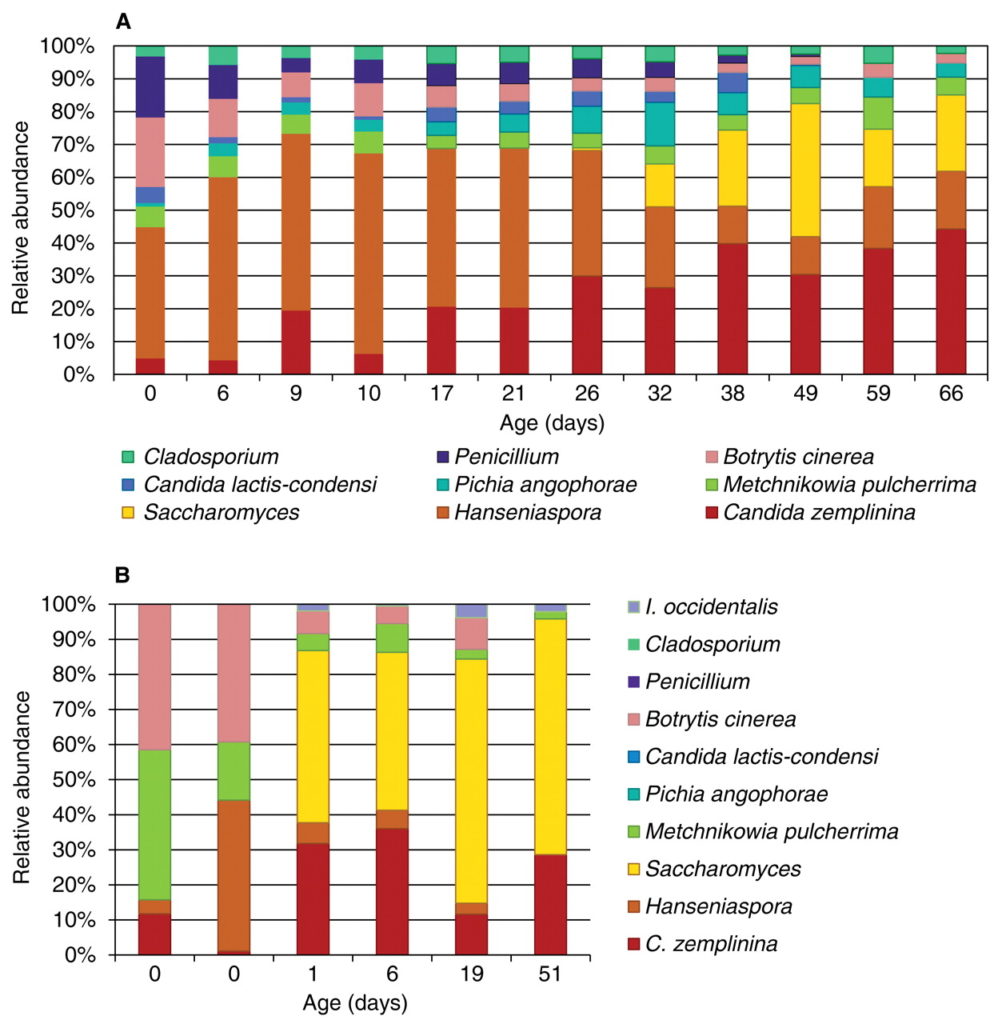

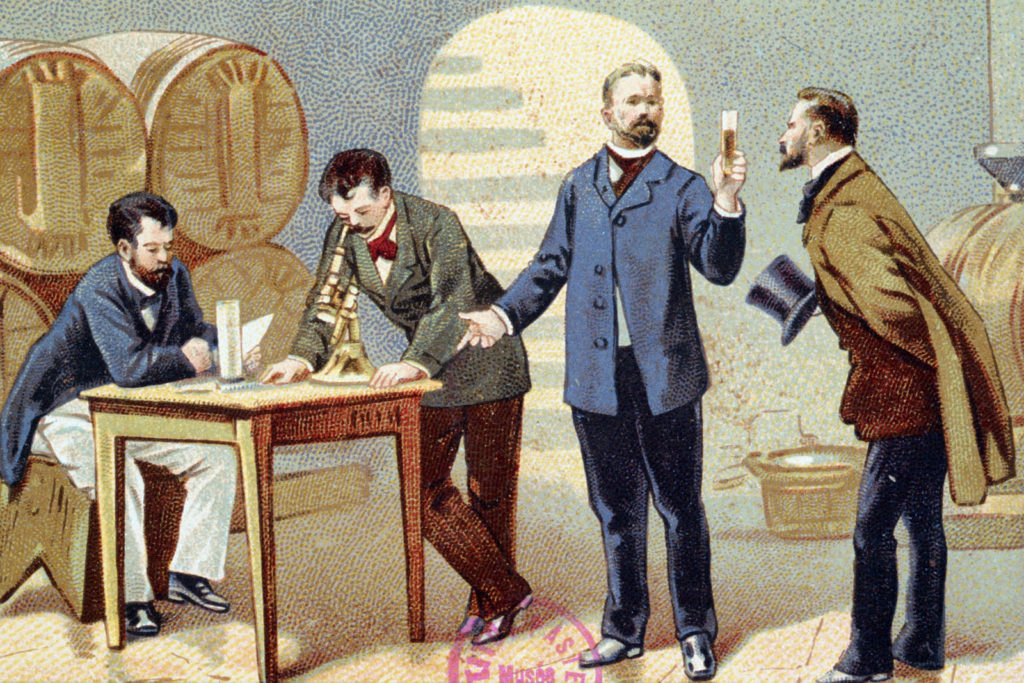

Beyond these aneducts and theories, for many at the time (as for the same Dandolo) "yeast" was some chemical compound. Only Pasteur, in the second half of the nineteenth century, put an end to this long diatribe, identifying it in a living organism.

However, Pasteur's work was not born from nothing and it was a very difficult and very controversial goal.

(to be continued…)

Next Wine Events

Here there are the next appointments where you can meet us and tasting our wines.

ProWein, in Duesseldorf (DE), 18-20 March 2018. Halle 16 / C22. C/o our importer Consiglio Vini.

Vinitaly, in Verona (I), 15-18 April 2018. Pav. 7 / Stand B5. C/0 our italian distributor Cuzziol GrandiVini.

Mostra Mercato dei Vignaioli FIVI, in Rome (I), 19-20 May 2018. Teatro 10, Cinecittà. Opening hours: 11.00-19.00. https://www.fivi.it/mercato-roma-2018-fivi-cinecitta-va-scena-territorio/

Fermentation in history 1: "It boils by its nature!"

After the post about fermentation, especially on the role of yeasts, I invite you on a little journey through history, to discover what people thought in the past about this crucial passage and how mankind came to understand it.

Fermentation has been used by man for at least 10,000 years for the production of beverages and foods: wine, beer, bread, yoghurt, cheese ... However, for millennia, humanity has done it without knowing how and why.

The word fermentation is ancient, derives from the Latin fermentum, from the root of the verb fervere which means to move, to boil. It arises from the observation of what is clearly visible: the bread leaven, swell and expand, the wine (or beer) boils.

But what did people think in the past of this phenomenon?

If we look for references in agrarian texts, from antiquity to the nineteenth century we don’t try hypothesis or questions about why and how it happens. Rather there are indications of practical work, useful to favor the process. This is natural: the agrarian texts in the past were mostly aimed at workers (of a certain rank), in particular the farmers. In the most ancient ages the problem is completely ignored (at least, as far as we know). In the texts of the Seven-Nineteenth century the whole process is cleared with the little phrase: "(the grape-juice) boils by its nature". So, it just happens, we're not asking why! These questions were left more to the philosophers and then to the scientists, but we will meet them later.

One of the most detailed agrarian texts of antiquity is the De re rustica by Columella (65 AD), "On Agriculture", which collects the sum of all the Roman agricultural knowledge. It is a text so well done and precise that it is considered by experts to be the first real agronomic treatise in history. It was so important that it remained the main reference for agronomy until the eighteenth century!

Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella lived in the 1st century AD, originally from Cadiz (present-day Spain). After a first military career in Syria, he retired to agricultural life in his estates in central Italy. He recounts that he was influenced in his interest in agriculture by his uncle, Marcus Columella, whom he describes as a cunning man and a great farmer. So his writings are not just a literary work (like other texts on agriculture at the time) but derive from direct experience, as well as from a curious mind that already appears very scientific.

Columella loves the agricultural life that he considers morally healthier than that of the city, as he tells in his work. According to him the farmer must directly manage his own farm and must have an excellent preparation on his work, based on the study of valid texts. It shows a particular sensitivity (compared to its times) on the use of servile labor.