Rute wins the TreBicchieri Award by Gambero Rosso

Michele and I were amazed when we learned that Rute had won the TreBicchieri Award by Gambero Rosso. We were surprised that Gambero Rosso had decided to reward not only the top Bolgheri wines, such as the Superiors, but also the Reds (the entry level). We are happy with it.

Thus, Rute also enters the group of our wines that have received critical acclaim, after Atis, Jassarte and Criseo. And it made it with a very important prize. It confirms, once again, that our entire production is of great value.

If I have to describe Rute ("red", in Etruscan) in one word, I would say elegance. Unfortunately, this word is very overused, even for wines that are anything but elegant. Elegance is made up of fine and complex aromas, a right concentration that is lightened (but not trivialized) by a great freshness, which translates into gustatory verticality. Rute is a red that also has very good aging potential, which can reach 10 years.

These characteristics arise from the Genius Loci of our vineyards, among the hills of Bolgheri. It is a marine and windy area, a Mediterranean territory. In our hills there are strong summer temperature variations between day and night. Our soils are alluvial, very deep and well-drained.

The quality of a winery is truly measured on the basic wines than the top ones. If they also are good, it means that the vintner are able to work well always, where it is not easy and obvious. And with a pinch of pride, I say that our craftsmanship is always the same: we take care with extreme love of all our vineyards and every batch of grapes that enters the cellar.

Switching from highly aged wines to younger ones should not mean a decline in the quality of the grapes or less well working . It means working differently. Once the most suitable particles of vineyard for one or the other type have been chosen, it means working at best to help the vines find different productive balances, in order to have grapes with different balances and concentrations, perfect for the type of wine they will originate. So it will be in the cellar: there will be different routes, but equally cared for.

Rute, neuer Jahrgang 2017

Bolgheri war jahrhundertelang ein schwieriges Gebiet,

hart und wild.

Heute ist es ein mediterraner Garten,

mit einer noch etwas wilden Schönheit.

Für uns ist es unser Zuhause,

es hat den Duft von den Wegen in der mediterranen Macchia,

den Salzgeruch der Sanddünen es hat den Klang der Wellen des Meeres,

das Lachen der Kinder, die in der Furt* baden ...

RUTE ist dieses uns vertraute Bolgheri,

dass wir in der Erde und in den Steinen unserer Weinberge suchen,

in unserer Handwerkskunst.

We are closed

As known, we are in an emergency Corona virus. So we adjust to the rules and we are closed. if you want our wines, we ship them your home. Write me at info@guadoalmelo.it for info.

We are closed at least until April 3 (inclusive), then we'll see.

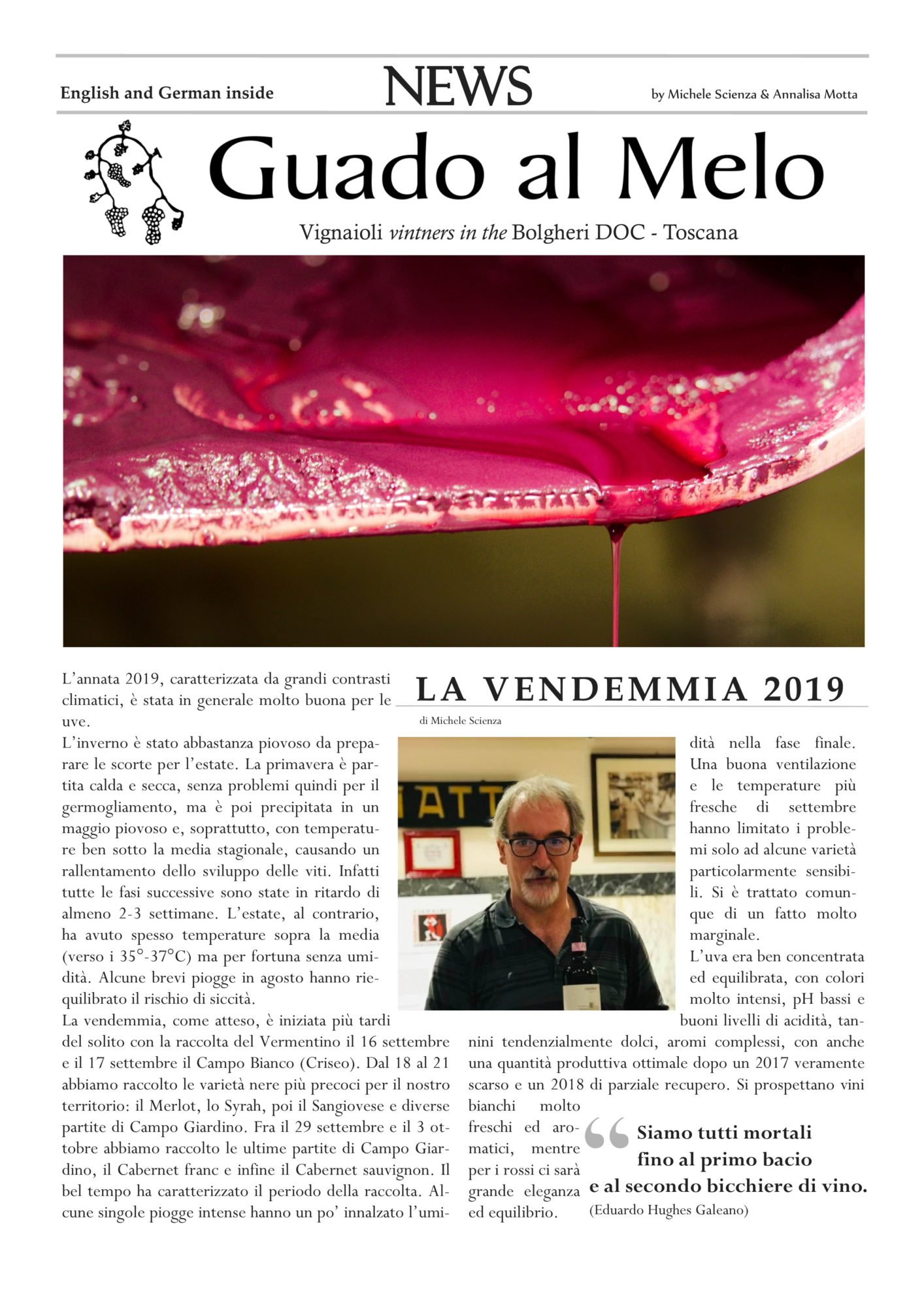

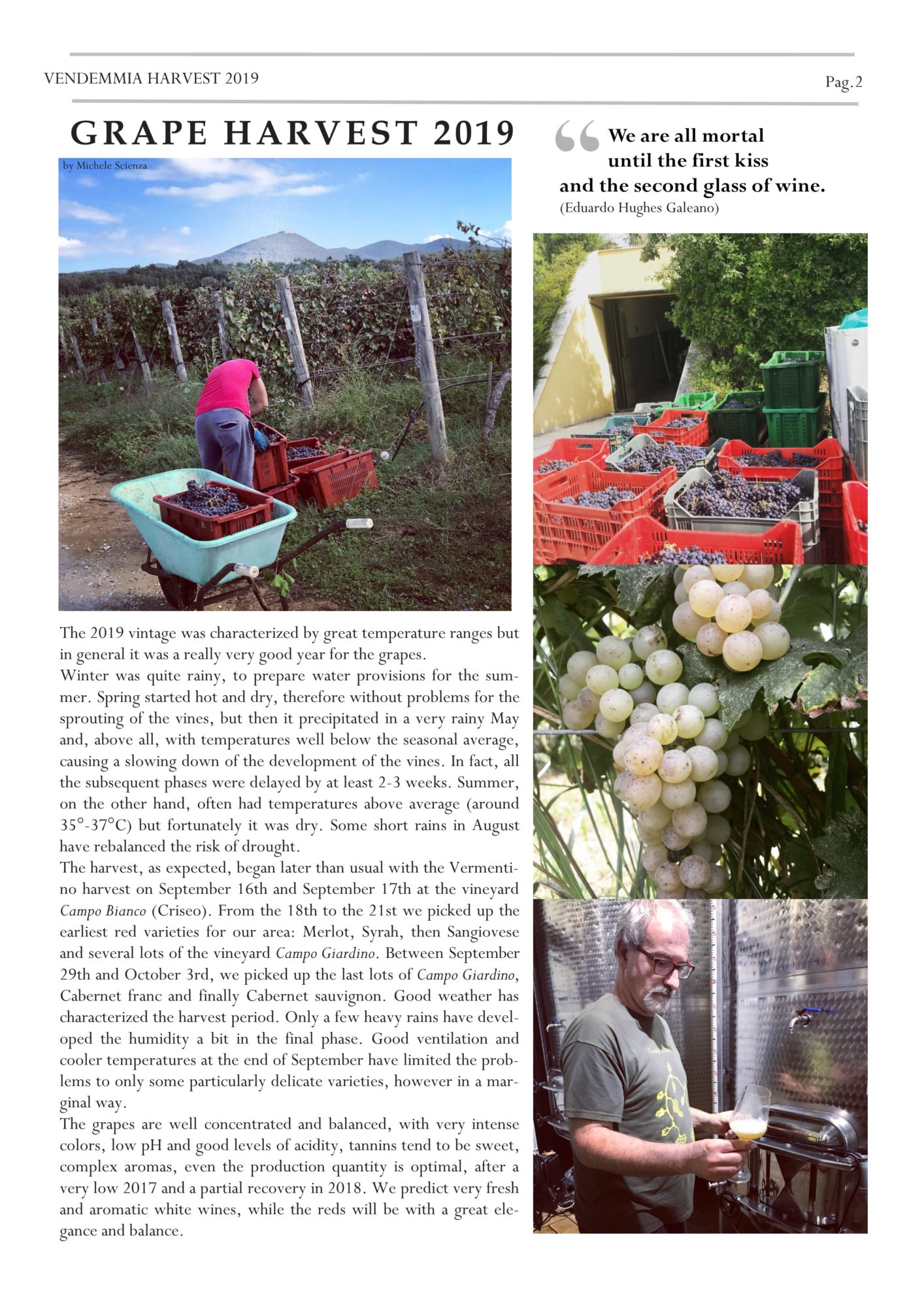

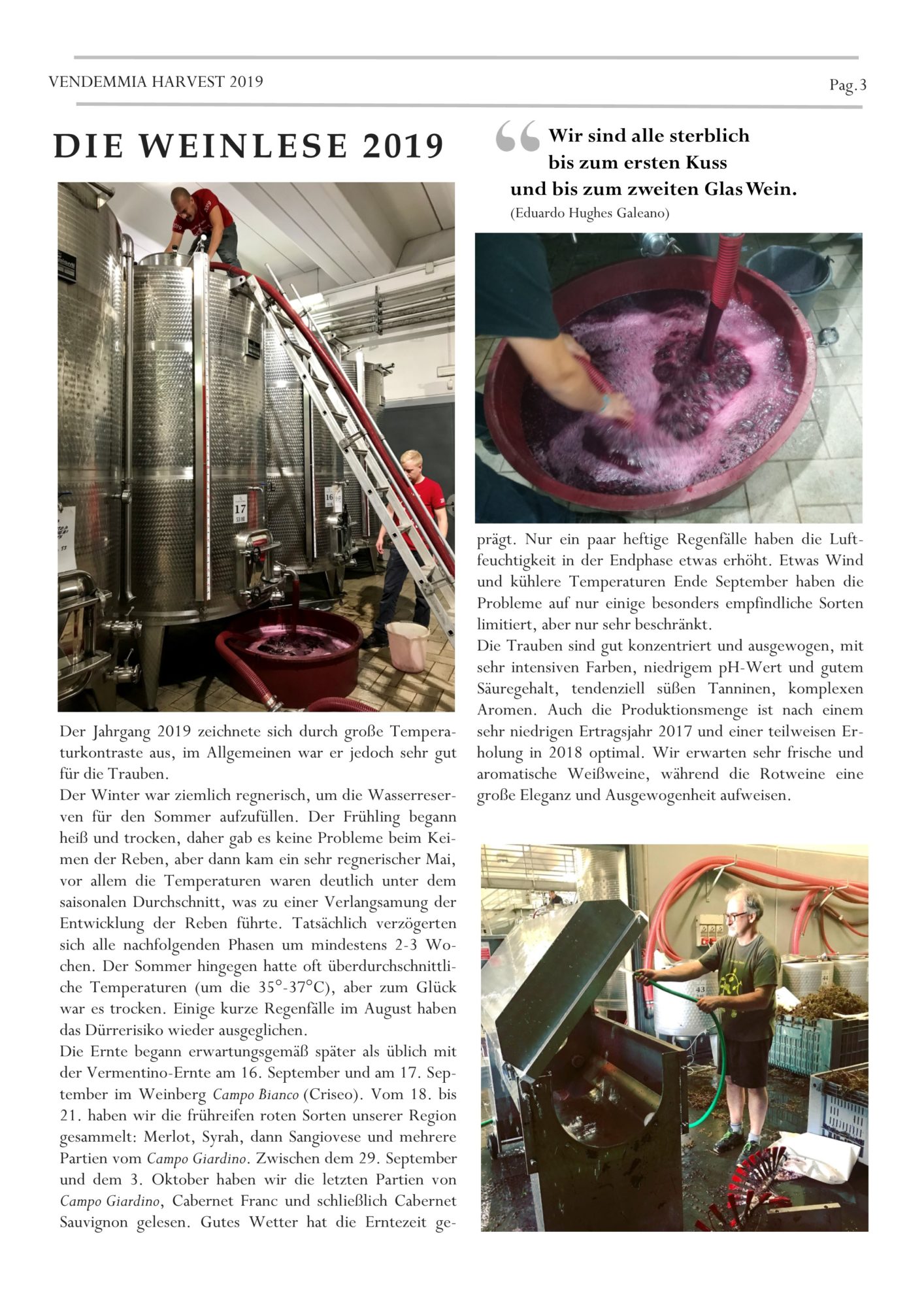

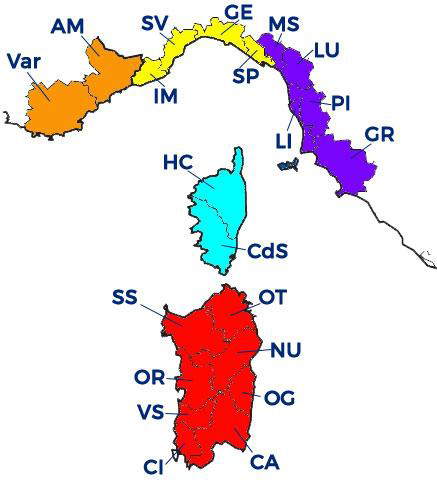

Guado al Melo News 2019

Wie es inzwischen Tradition ist erinnern wir uns an das zu Ende gehende Jahr 2019, mit einer kleinen Publikation in drei Sprachen (Italienisch, Englisch und Deutsch).

Es beginnt mit der Weinlese, ein entscheidender Moment für uns des Jahres, erzählt dann aber die wichtigsten Ereignisse und einige Neuigkeiten für das neue Jahr.

In diesem Jahr stammt das Zitat von Edoardo Hughes Galeano, einem uruguayischen Journalisten und Schriftsteller, einer der größten Persönlichkeiten der zeitgenössischen lateinamerikanischen Kultur, der 2015 verstorben ist. Es gefiel uns, weil es mit subtiler Ironie unterstreicht, was im Wesentlichen die Funktion von Wein seit jeher ist. : um unseren Tagen Freude zu bereiten, sowie die Liebe, die uns die Sorgen des Lebens vergessen lässt.

Hier finden Sie auch die pdf-Version.

Eccellenze di Toscana 2019

Saturday 30 November and Sunday First Dicember, we will be at the tasting event "Eccellenze di Toscana", during the Fair Wine & Food in Progress, at the Stazione Leopolda in Florence.

There will be Michele Scienza, from 10.00 am h to 7.00 pm. See you.

Anerkennungen von unserem Atis Bolgheri Superiore

Der renommierte Leitfaden Veronelli hat unseren Atis Bolgheri DOC Superiore 2016 mit dieser wichtigen Auszeichnung ausgezeichnet.

Übrigens belohnen sie Atis zum dritten Mal in Folge (mit Ausnahme von 2014, das wir nicht produziert haben) mit drei bemerkenswerten Jahren für unser Territorium: 2013, 2015, 2016.

Danke an das Personal.

Atis 2016 one of the best Italian wines for Bibenda

Thanks so much to the Italian Sommelier Foundation. In their wine guide Bibenda, they awards the maximum score (5 grapes) to our Atis Bolgheri DOC Superiore 2016.

The Italian Sommelier Association (AIS) awards Jassarte 2016 the best score (4 vines)

Many thanks to the AIS sommeliers which, in their guide "Vitae", awards with their maximum recognition (the 4 vines) our Jassarte 2016 Toscana IGT Rosso. It is a great honor for us.

Its first official release will be on the occasion of the AIS awards ceremony, Saturday 26 October, from 11.00 to 19.00, in Rome, at the "Nuvola" Congress Palace.

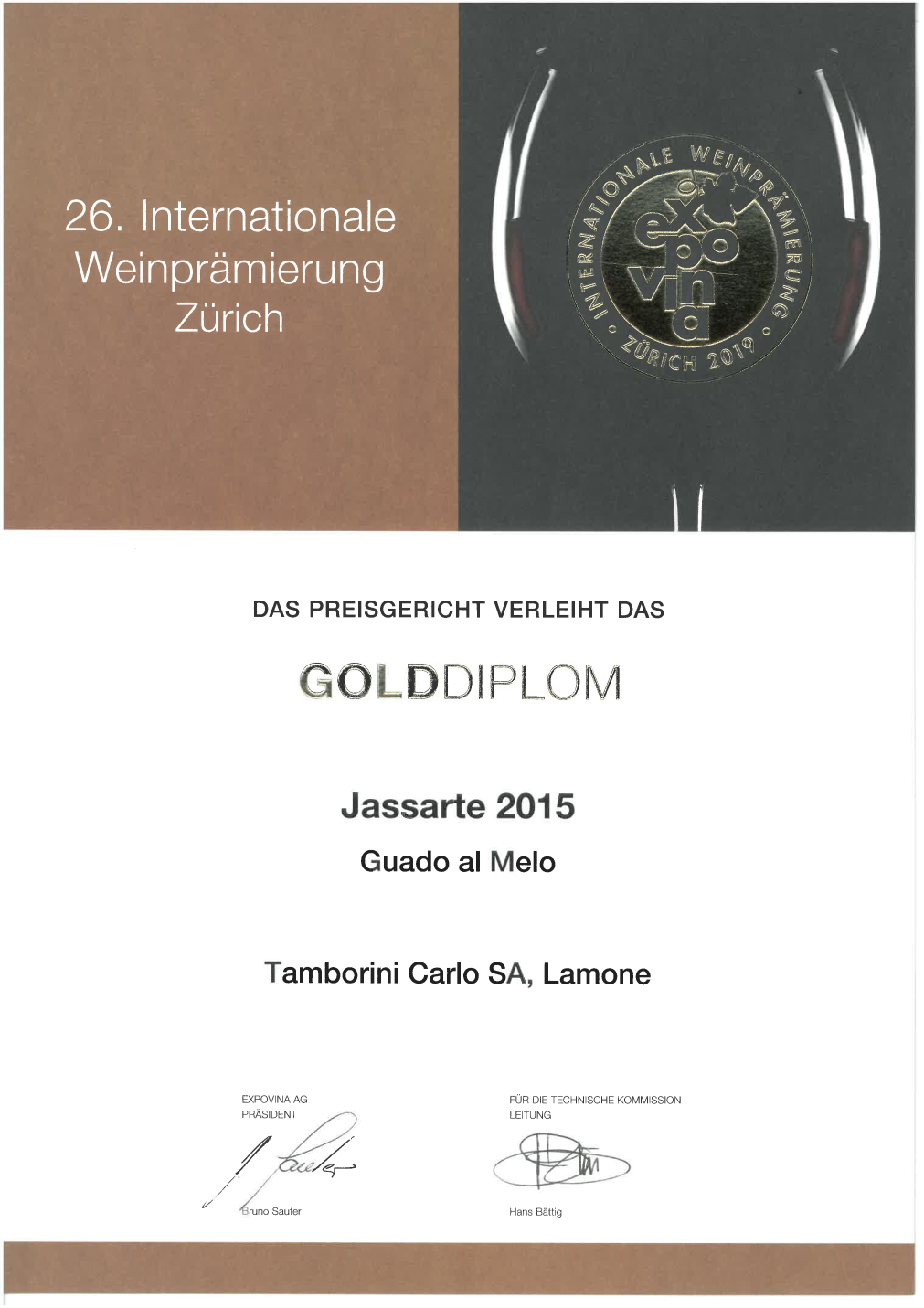

Jassarte 2015: Gold Diplom

Wir freuen uns mitzuteilen, dass Jassarte 2015 den Internationale Weinpraemierung Expovina in Zürich gewonnen hat.

Happy Easter: we are open

We are open on Saturday, Monday and on April 25 (they are Italian public holidays), h 10-13 15-18.

We are waiting for you!

Guado al Melo ist "Quality Made"

Ich hatte bereits über dieses Projekt geschrieben, das vor etwa einem Jahr begann. Der Zertifizierungsprozess ist nun abgeschlossen: Guado al Melo wurde als Unternehmen anerkannt, das die Werte von Cultural Identity trägt.

Quality Made ist eine hochwertige Cultural Identity-Marke, die Unternehmen zertifiziert, deren Aktivitäten auf Prinzipien der kulturellen, ökologischen und sozialen Nachhaltigkeit basieren.

Quality Made richtet sich an Reisende, die echte und einzigartige Orte suchen, ein umweltfreundliches Reiseerlebnis, das die örtlichen Gemeinschaften respektiert.

Quality Made-zertifizierte Unternehmen verbinden tiefe Wurzeln in ihrem Gebiet, die Beachtung der Besonderheiten der lokalen Kultur, besondere Sorgfalt bei der Schaffung qualitativ hochwertiger Produkte und Dienstleistungen sowie ihre starke handwerkliche und territoriale Konnotation.

Die im Jahr 2018 gegründete Marke ist in Frankreich und Italien tätig und umfasst eine erste Gruppe von 75 Unternehmen.

7. bis 10. April: Vinitaly in Verona

7. bis 10. April: Vinitaly in Verona, wir sind in Halle 7, Stand B5, bei unserem Vertriebspartner für Italy Cuzziol GrandiVini. Wir werden sowohl Michele als auch ich sein, Annalisa.

24.-25. März: Vinissima, Tamborini Vini-Verkostung, unser Importeur in der Schweiz

24.-25. März: Vinissima, Tamborini Vini-Verkostung, unser Importeur in der Schweiz. Es wird Michele geben. Tamborini Vini liegt in Lamone über Serta 18. Tel. +41 919357545 www.tamborinivini.ch info@tamborinivini.ch

17. bis 19. März: ProWein in Düsseldorf

17. bis 19. März: ProWein in Düsseldorf: Wir sind in Halle 16, Stand J25, bei unserem Importeur für Germany Consiglio Vini. Es wird Michele geben.

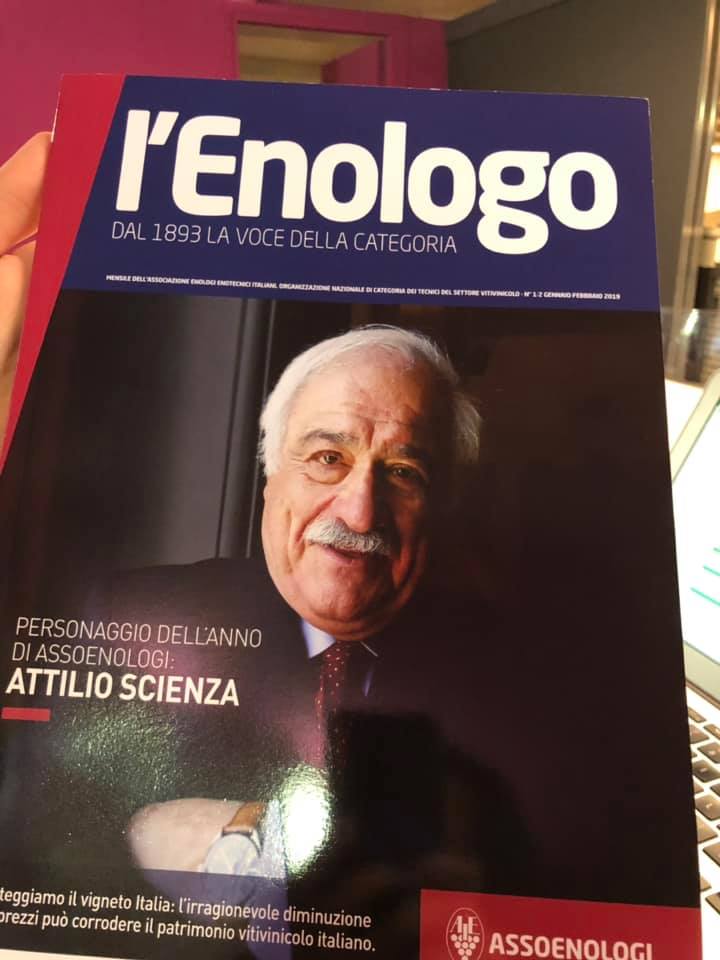

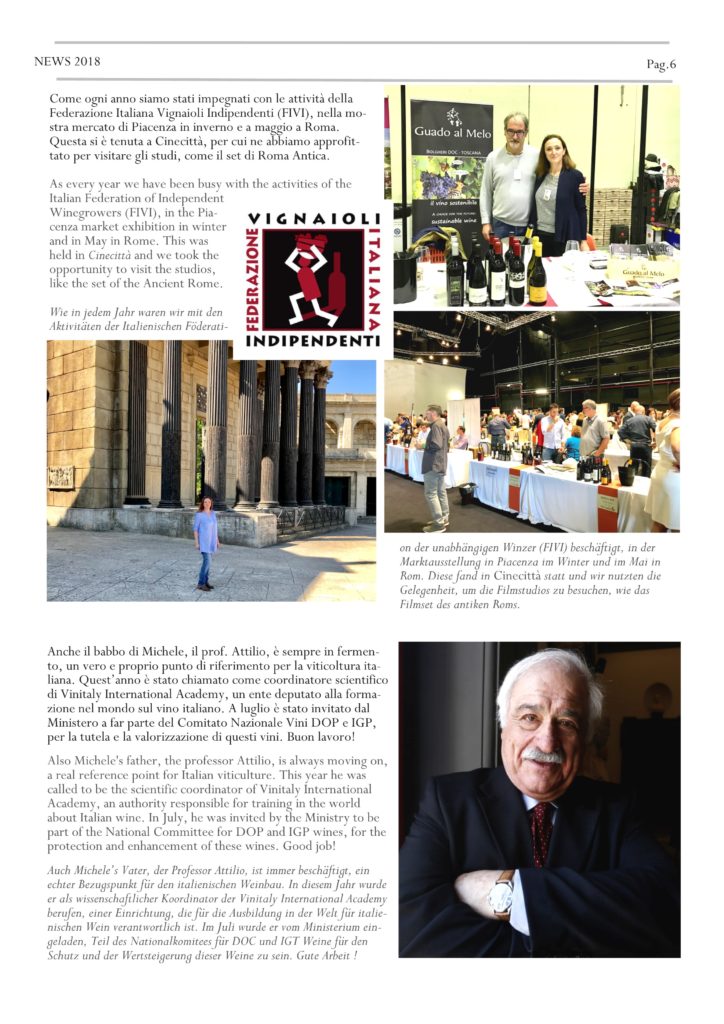

Attilio Scienza ist ein Mann des Jahres 2019 für Assoenologi

Prof. Attilio Scienza, Michele's Vater, bekannter Experte und Professor für Weinbau an der Universität Mailand, ist ein Mann des Jahres 2019 für Assoenologi, den italienischen Verband der Önologen.

Jassarte 2015

Der Professor Attilio Scienza hat in Guado al Melo eine ampelographische Sammlung (ein Weinberg mit vielen Rebsorten) für Studienzwecke geschaffen. Michele entschloss sich, einen Wein aus diesem Weinberg herzustellen, wie aus den alten gemischten Sätzen von früher. Er wollte den Wein wiederentdecken, wie er in der Vergangenheit (von seinen Ursprüngen bis in das 20. Jahrhundert) konzipiert wurde, das heißt als absoluter Ausdruck des Territoriums, über die Rebsorten hinausgehend, ein Wein, der aus einem Weinberg als einzigartige und nicht wiederholbare Identität entsteht, Ergebnis der Territorialforschung, die seine ganze Arbeit charakterisiert. Jassarte wird nur in den Jahrgängen die für gut genug befunden werden hergestellt.

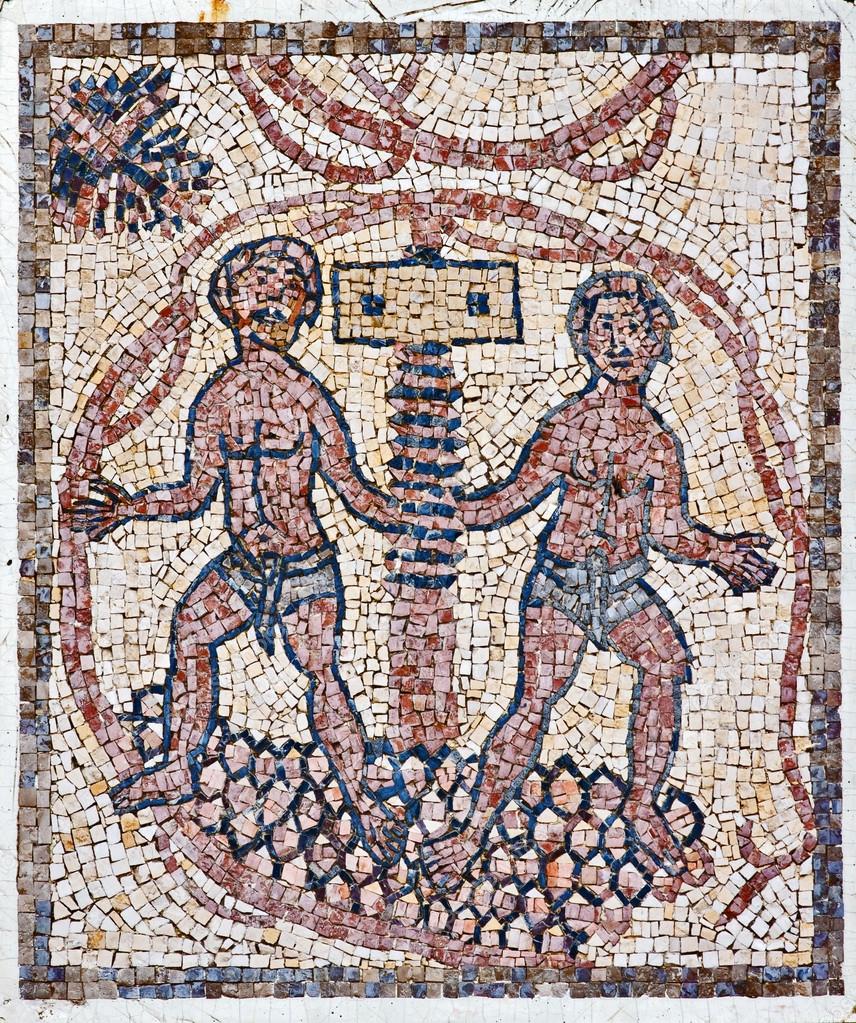

Wir suchten für den Wein nach einem Namen, der an die Ursprünge des Weinbaus, die zwischen dem Mittelmeerraum und dem Kaukasus, dem Westen und dem Osten liegen, erinnert. Der griechische Historiker Herodot schrieb, die Grenze zwischen diesen beiden "Welten" sei durch zwei Flüsse gekennzeichnet, dem Indus im Süden und dem Jassarte im Norden. Jassarte ist für uns zum Symbol eines idealen Grenzlandes geworden, zu einem Ort, an dem sich Kulturen treffen und außergewöhnliche Dinge schaffen. Auf dem Etikett, aus etruskischer Kunst, befinden sich zwei kleine Erntesatyrn.

Erster produzierter Jahrgang: 2003

Nicht produzierte Jahrgänge: 2002-2010-2014

Jahrgang 2015: Das Jahr war nach einem schwierigen Jahr 2014 sehr ausgeglichen. Der regenreiche Winter und Frühling, lieferten dem wie üblichen heißen und trockenen Sommer die Wasserreserven. Die Reifung war regelmäßig, auch dank unserer Sorgfalt, die wie immer darauf ausgerichtet war, das Gleichgewicht der Reben zu fördern. Das gute Wetter hielt während der ganzen Erntezeit an, welche von Ende August bis Anfang Oktober gedauert hat. Der großartige Jahrgang brachte einen Jassarte mit sehr tiefem, fast dunklem Farbton hervor. Im Mund ist er voll und weich, aber immer elegant und ausgeglichen, von langem Abgang und mit einer reichen und komplexen Aromavielfalt.

REBSORTE / WEINBERG: entsteht aus dem Weinberg Campo Giardino, etwas weniger als 1 Hektar, aus circa 30 roten Rebsorten im gemischten Satz angebaut. Er wurde im Winter 1998/99 an den unteren Hängen des Hügels von Segalari in einem kleinen Tal in Ost-West-Richtung angepflanzt. Das Klima ist mediterran und wird durch die tyrrhenischen Meereswinde gemildert. Das hügelige Gebiet hat die kühlsten Temperaturen der Denomination (DOC), mi dem maximalen Temperaturunterschied im Sommer zwischen Tag und Nacht. Der Boden ist aus Schwemmland, sehr tief, sandig- lehmig, mit Lehm Einschlüssen, reich an Kieselsteinen. Wir bauen die Reben an mit der Erfahrung und dem Know-how unserer Familie aus Winzern seit Generationen und verfolgen sie Tag für Tag. Wir verwenden integrierte und nachhaltige Weinbaumethoden, das heißt, wir wählen die besten derzeit verfügbaren Systeme für eine optimale Produktion, mit den geringsten Auswirkungen auf die Umwelt und ohne Rückstände ihm Wein.

HERSTELLUNG und AUSBAU: Unsere Arbeit ist handwerklich, mit Kompetenz, Erfahrung und größter Liebe zum Detail, mit dem Ziel, die territorialen Eigenschaften der Trauben hervorzuheben. Campo Giardino wurde in kleinen Posten aus verschiedenen Rebsorten gelesen, je nach Reifezeit, während des ganzen Septembers und dann Gruppenweise verarbeitet. Die ausgewählten Trauben wurden innerhalb weniger Minuten nach der Ernte entbeert und sehr schonend gepresst, ohne Schwefel Zusätze um die Artenvielfalt der der Hefen zu erhalten. Vergärung und Mazeration wurden durch häufiges manuelles Umpumpen begünstigt. Die Mazeration dauerte etwa 13 bis 17 Tage. Der Wein wurde dann 24 Monate lang in 225-liter-und 500 liter Eichenfässern, hauptsächlich ältere, gelagert. In den ersten 22 Monaten blieb der Wein auf der Feinhefe (Hefetrub), wobei jedes Fass einmal pro Woche manuell umgerührt wurde. Danach wurde der Wein ruhen gelassen und einige Male umgefüllt, um ihn zu reinigen (da er nicht gefiltert wird). Am Ende wurde Jassarte aus den verschiedenen Fässern, indem man die Identität des Weinbergs respektiert hat, in einen großen Stahltank gefüllt und etwa 4 Monate dort gelassen damit er sich auf natürliche Weise vermischt. Nach der Abfüllung wurde er 12 Monate lang unter den besten Lagerbedingungen in der Flasche ruhen gelassen. Der Einsatz von Schwefeldioxid ist minimal.

Frohe Weihnachten und ein gutes neues Jahr

Wir sind für Feiertage vom 22.12.18 bis einschließlich 06.01.19 geschlossen.

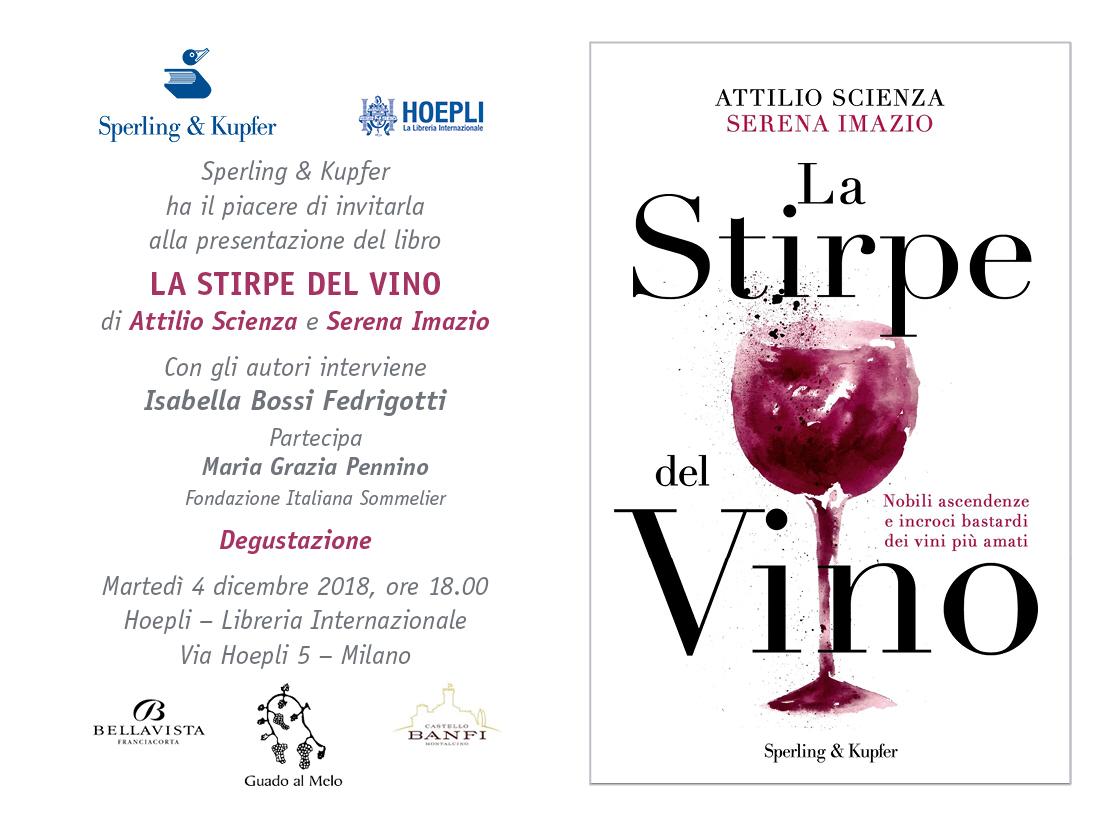

Attilio Scienza presents his last work: "La stirpe del vino" (The bloodline of wine)

On Tuesday 4 December at the bookshop Hoepli in Milan, at 6.00 pm, our prof. Attilio Scienza will present, with the co-author Serena Imazio, his new book "La stirpe del vino" ("The bloodline of wine") Ed. Sperling & Kupfer.

In this book they tell about the origins, relatives (sometime unimaginable) and geographic travels of the main varieties of grapes, through history, myth and science,

Isabella Bossi Fedrigotti (Italian writer and journalist) will also speak. Maria Grazia Pennino (Sommelier AIS) will support the tasting of some of our wines and other estates (Bellavista from Franciacorta and Banfi from Montalcino) who kindly offered some of their best products.

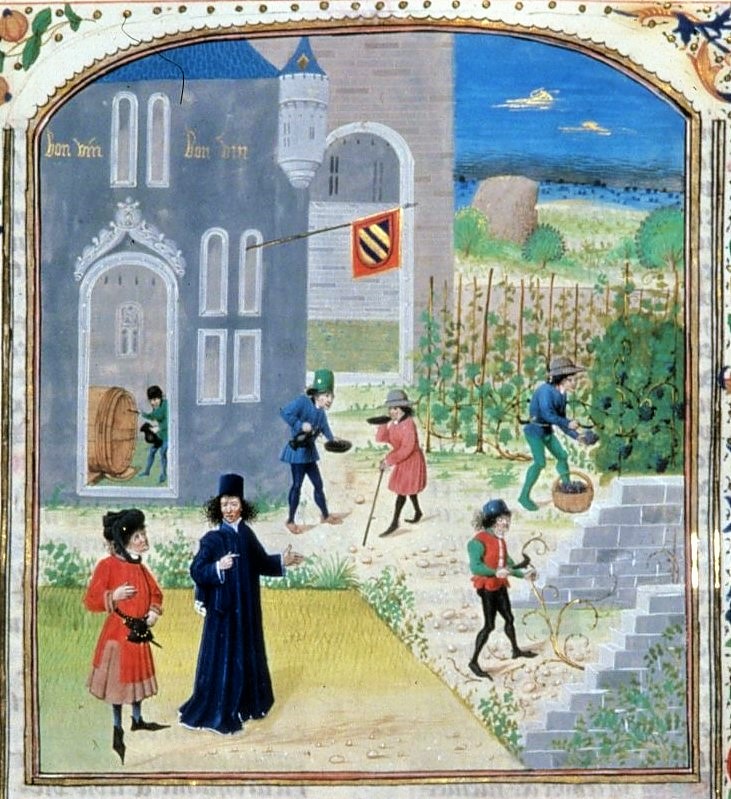

Wine and the Etruscan (I): the first winegrowers

Wine and the Etruscans is a fascinating theme but little known. When people thinks at the antiquity of Italian wine, they thinks almost exclusively to Rome. Obviously Rome has played a fundamental and extraordinary role in the history of wine, but also the Etruscans have been relevant. Above all, they came first and taught so many things to the Romans.

Why do the Etruscans interest we so much?

Because they were the first inhabitants of our lands and were the first winegrowers in Italy. Millennia ago, therefore, he was here in our place, doing our own work!

But who were the Etruscans? Read below ... if you already know this part, skip it.

After a territorial decription, we will dedicate ourselves specifically to wine.

“... Etruria was so powerful that the fame of it filled not only the land, but the sea as well, and through all of Italy, from the Alps to the Strait of Sicily. “

Livy, Ab Urbe Condita, book I, I c. b.C.

Our territory was characterized by a row of hills parallel to the sea, in the middle of a marshy flat area (the North Maremma), inhospitable and where proliferated malaria. Since prehistoric times the people lived in the hills practicing hunting and gathering wild products. Later, the first permanent settlements arose and thence the first early agricultural societies that gave origin to the Etruscan civilisation.

The great territory wealth was the big mining resources (above all iron), which exploitation initiated from the Bronze Age (12th century BC). In contrast to the large-scale inurbations in southern Etruria, few cities rose in this area, and the populations remained scattered. Three great city-states dominated the coastal area: Pisa, which controlled the northernmost stretches; Volterra dominating the Cecina Valley to the sea; and Populonia in the south. The Etruscans, excellent hydraulic engineers, reclaimed part of marshy plains near the sea, and used it for agriculture.

Our territory, Castagneto Carducci e Bolgheri, was part of city-state of Populonia. Its ancient remains are at few Km from our winery, seaward the charming Gulf of Baratti.

Populonia declined on the Roman period.

decadde come città già in epoca romana. Claudius Rutilius Namatianus, on V c. A.C., passing along the coast with his boat, saw only ruins:

Close at hand Populonia opens up her safe coast,

where she draws her natural bay well inland...

The memorials of an earlier age cannot be recognised:

devouring time has wasted its mighty battlements away.

Traces only remain now that the walls are lost:

under a wide stretch of rubble lie the buried homes.

Let us not chafe that human frames dissolve:

from precedents we discern that towns can die.

Claudius Rutilius Namatianus, 417 AC

De Reditu Suo (About his return), I, 401-414

The most important Etruscan site in Castagneto is the Tower of Donoratico, unfortunately not visited because it is located in a private property.

So, the Etruscans played a decisive role in the spread of the wine culture in the western world.

They were the first to develop viticulture in Italy introducing their practices into much of the peninsula, from the north (Emilia Romagna) to the south (Campania), Rome included. Great navigators and traders, they came into contact with the cultures of the eastern Mediterranean and introduced in the West cultural aspects of wine, as the religious symbolism and ritual consumption in the symposia. They brougth from East also the oriental grape varieties. Finally, they also spread wine and its culture via commercial channels to the people of western Europe who were still ignorant of this beverage, such as the Celts, the German tribes, and the Iberian peoples.

However, we will go into more detail in the next post.

RECOMMENDED TO VISIT

Parco Archeologico di Baratti e Populonia, loc. Baratti, Piombino.

Collezione Gasparri, Via di Sotto 8, Populonia Alta.

Museo Archeologico del Territorio di Populonia p.za Cittadella 8, Piombino.

Parco Archo-minerario di San Silvestro, via di Sa Vincenzo Sud 34/b, Campiglia M.ma.

Museo del Palazzo Pretorio, via Cavour, Campiglia M.ma.

Museo Archeologico di Cecina, Villa Guerrazzi loc. La Cinquantina, San Pietro in Palazzi.

Museo Civico Archeologico di Rosignano M.mo, Palazzo Bombardieri, va del Castello 24.

Area Archeologica di San Gaetano a Vada.

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Castiglioncello, via del Museo 8, Castiglioncello.

Museo Etrusco Guarnacci, Via Don Giovanni Minzoni 15, Volterra.

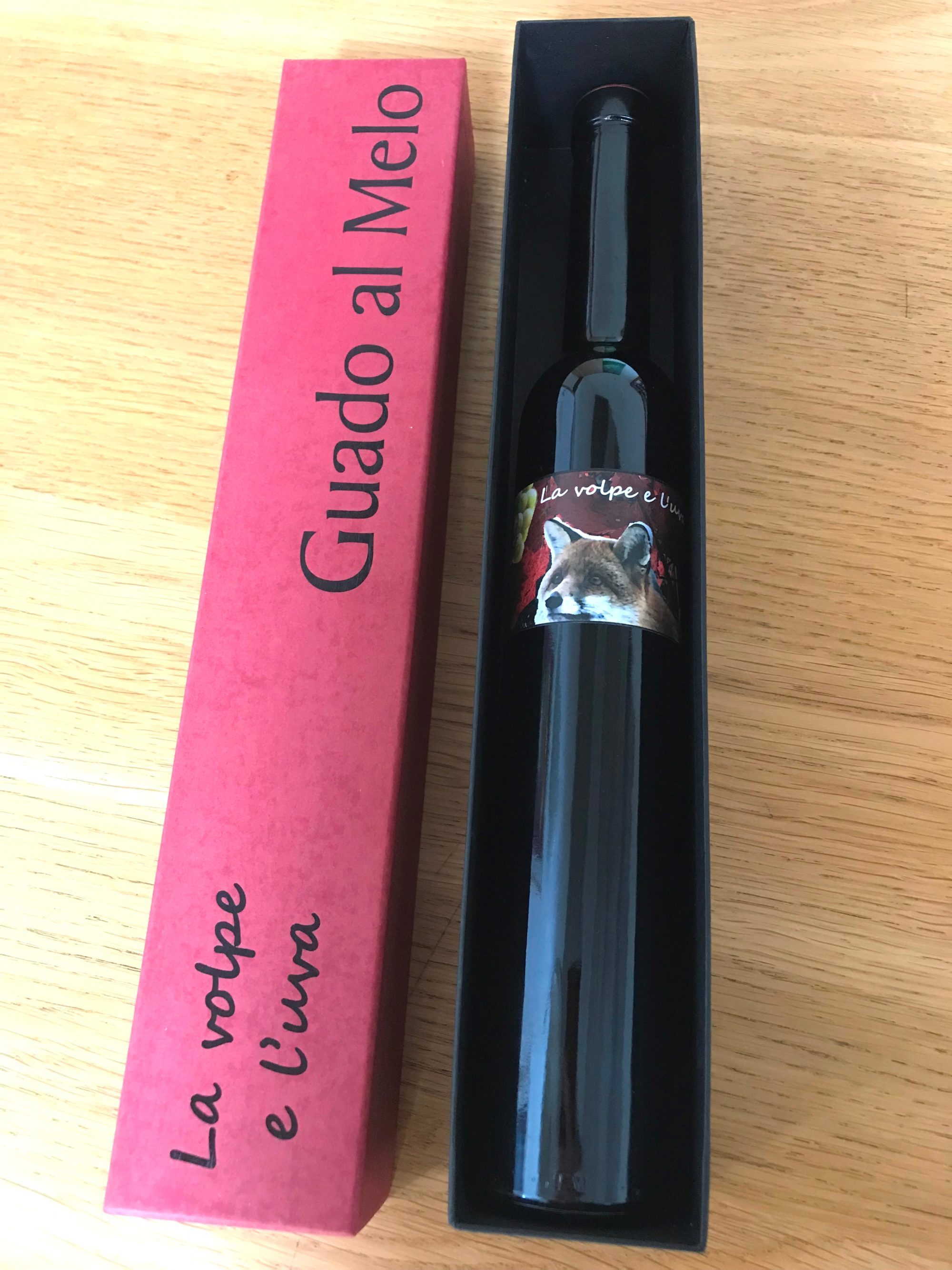

Raisin wine, Malvasia grapes based, "La volpe e l'uva": natural sweetness

I'm presenting you a new wine, a very little production that we made to have a excellent raisin wine but not too sweet.

I often dislike sweet wines because they are "heavy", quite nauseous. So, Michele and I decided to produce a perfumed and full-body wine, but with a moderate sweetness.

Its aromas are fantastic: white flowers, apricot, cinnamon, aromatic herbs, orange zest, raisin grapes... In mouth, it is full, with a pleasant sweetness. It is very good as aperitif or after-dinner. It is also optimal in pairing with mature or blue cheeses or fois-gras... It is also good pairing with not too sweet desserts, for exemple with desserts with nuts or chocolate.

Why the name "La volpe e l'Uva" (The fox and the grapes)?

Do you remember the famous fable of Phaedrus " The Fox and the Grapes " ? In the summer nights we often see foxes in our vineyard. However, rather than on the moral end of the fable, we focus on the eager gaze of the fox, the intense desire for that perfect fruit, unique and precious (as this wine). I made the label thinking to this idea: a great desire that we want to satisfy. The bicolor box is very beautyfull.

Why "natural sweetness"?

Because this wine is produced in artisanl way, without added sugars. Michele made it with an ancient and traditional method, called "mistella". A little portion of the grapes are picked-up and dried on trellis in a cool and airy place. Then they get pressed in a wooden manual press, and added to the must in fermentation of the fresh grapes. The addition of this concentrate juice causes the arrest of the process, leaving a natural sugar residue. It was aged for 4 years in oak not-new barrels.

Malvasia is a traditional grapes, often used in Italy to produce sweet wines. We have few plants of Malvasia, so we produced only 593 bottles.

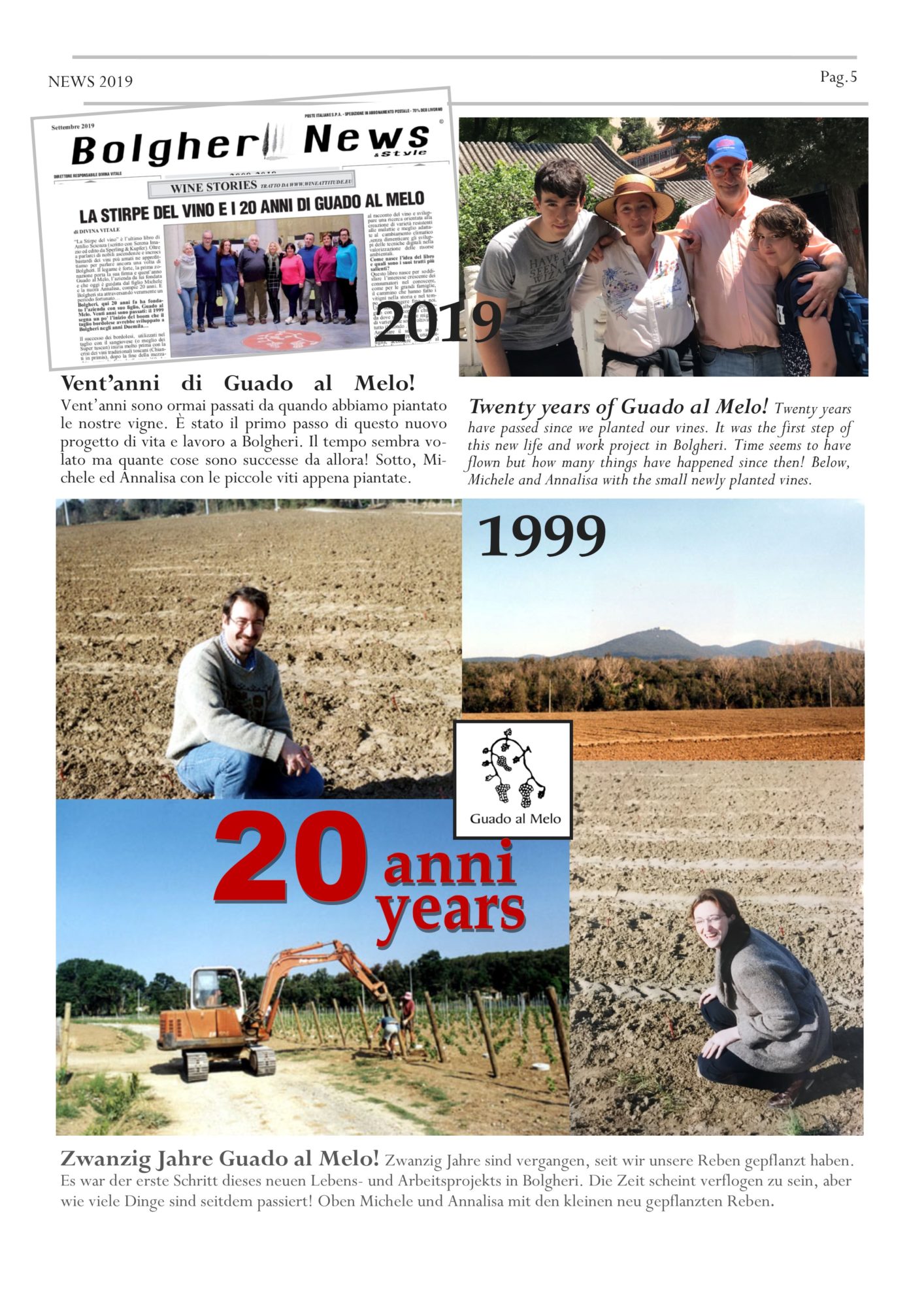

A network for "conscious travelers", to discover the cultural identity of a territory

In winter a project was presented us, aimed at creating a tourism brand, focused on enhancing the culture of the territory. Those who know us (or know Guado al Melo) certainly know that it seemed made for us!

We compiled the membership form and now we have the news that we have been selected to be part of the pilot project!

Here is a summary of what it is:

WHERE. The project is centered on a strip of Mediterranean Europe, joined by similar natural environments and cultural continuity: the Italian coastal strip of Tuscany, Liguria and Sardinia, the French Mediterranean coast and Corsica.

WHERE. The project is centered on a strip of Mediterranean Europe, joined by similar natural environments and cultural continuity: the Italian coastal strip of Tuscany, Liguria and Sardinia, the French Mediterranean coast and Corsica.

WHAT. The project aims to give birth to a network of small local businesses, accumulated by deep territorial and cultural roots. The idea is to present a particular path to "conscious travelers", ie people looking for non-trivial tourist experiences, eager to meet local realities capable of deepening the narration of their territories, savoring real and unique experiences. The network integrates places of memory and nature (such as museums, cities of art, parks) but also places of the human present, represented by itineraries of taste, typical and artisanal productions.

SUSTAINABILITY. The realities that become part of the project must respond to the fundamental principles of cultural, environmental and social sustainability.

THE PROJECT. For now we are still at the beginning. Among the many candidates, 80 (of the territories indicated) were selected , chosen for their particular correspondence to the spirit and purpose of the project. These pilot companies, including us, will now be accompanied in a certification process and (if necessary) adaptation to all the required standards. After that the project can be opened to other realities and, at the same time, promoted to the public.

The project is called S.MAR.T.I.C., acronym of «Sviluppo Marchio Territoriale Identità Culturale», "Development of Territorial Cultural Identity Brand". It is co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund from the INTERREG Italy-France Maritime Program 2014-2020. http://interreg-maritime.eu/it/web/s.mar.t.i.c./progetto

The reference for the territory of Livorno is the cooperative "Itinera Progetti e Ricerche" gbenucci@itinera.info +39 0586 894563 www.itinera.info/blog/

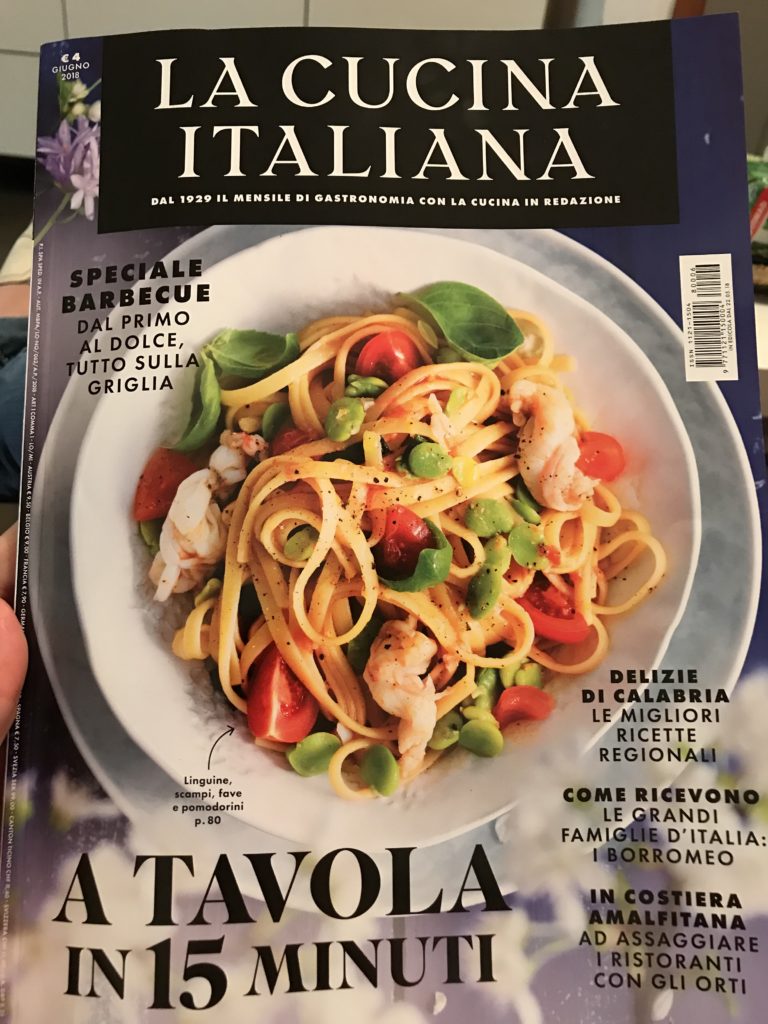

Criseo wine conquers all: even "La Cucina Italiana" magazine recommends Criseo 2016

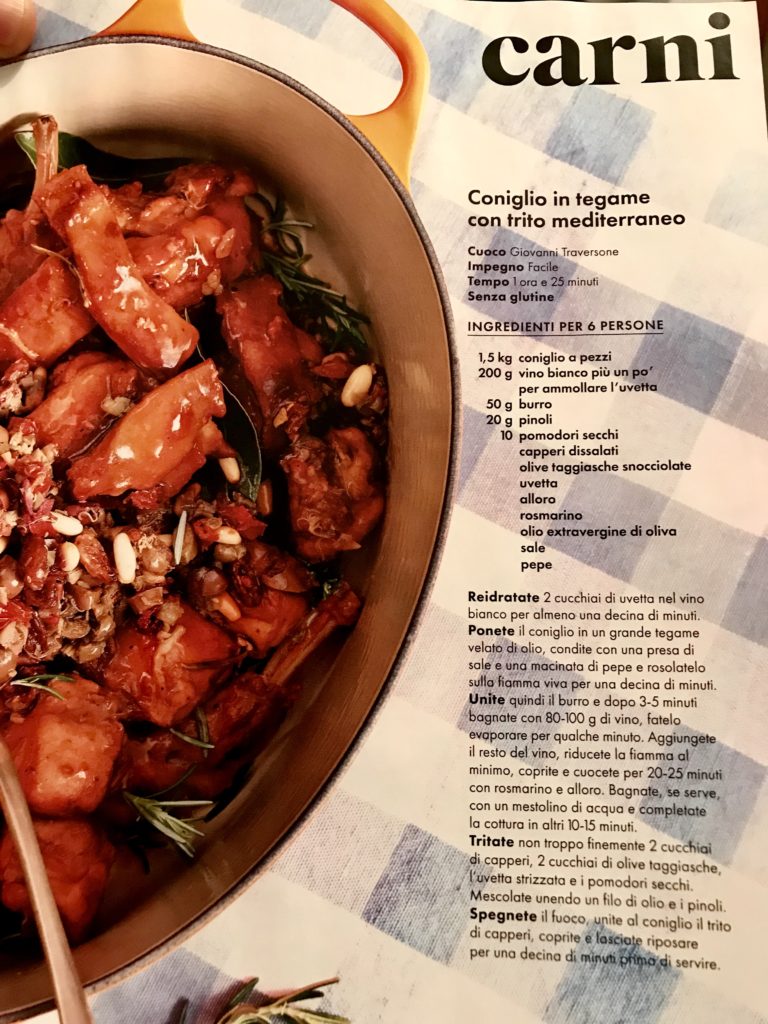

Mediterranean rabbit:

1,5 Kg rabbit

200 g white wine, other for raisins

50 g butter

20 g pine nuts

10 dried tomatoes

Desalted capers

Taggiasca olives

Raisin

Laurel

Rosemary

Extravirgin olive oil

Salt and pepper

Soak 2 tablespoons of raisins in white wine for 10 minutes.

Brown the rabbit pieces for about 10 minutes in a large pan with a little oil, salt and pepper. Add the butter and, after 3-5 minutes, 80-100 g of white wine, and after 2-3 minutes the rest of wine.

Then lower the heat to a minimum, add laurel and rosmary, close the lid and cook for about 20-25 minutes. Then add a little water (if necessary) and cook again for 10-15 min.

Meanwhile coarsely chopped 2 tablespoons of desalted capers, 2 tablespoons of pitted olives, the dried tomatoes, and the squeezed raisins. Add a little oil and the pine nuts to the mixture.

At the end of cooking, add the Mediterranean mixture to the rabbit, stir, close and let it rest for about 10 minutes.

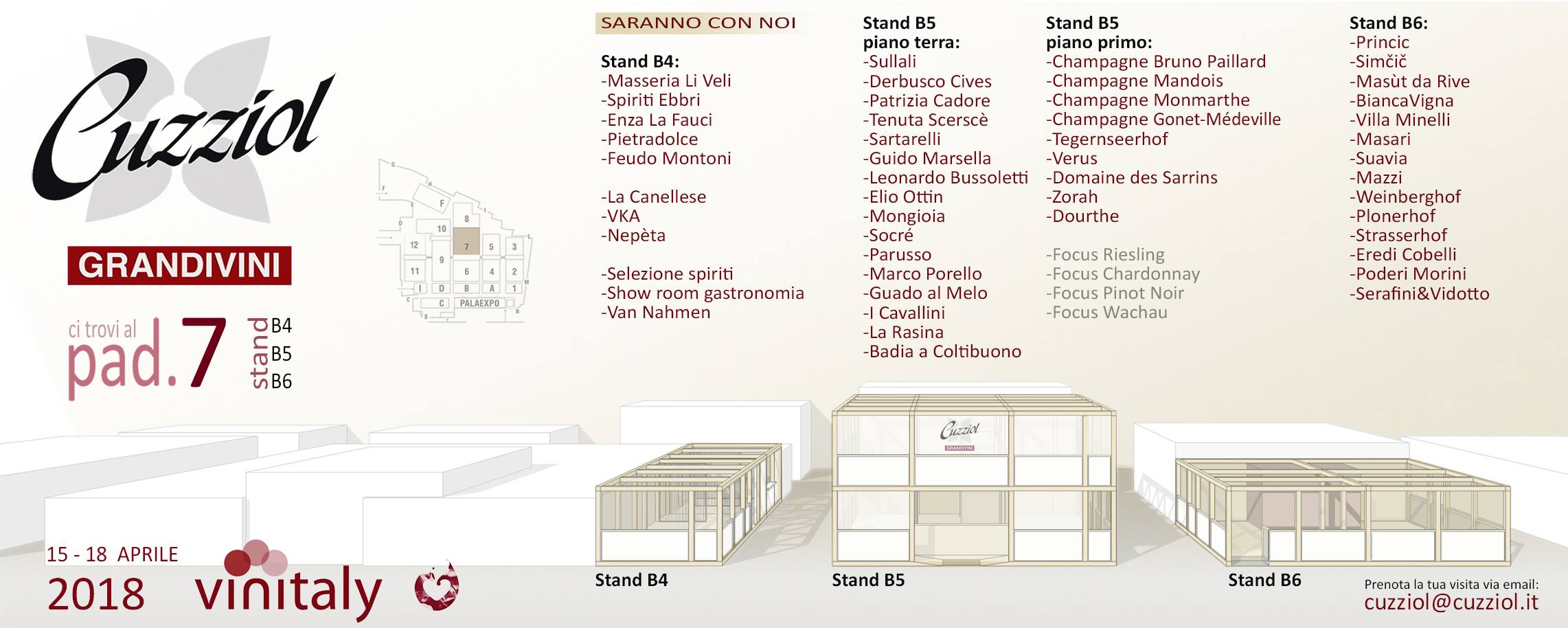

Are you ready for Vinitaly?

We are ready! We will be at Pav. 7, stand B5, c/o our distributor for Italy CuzziolGrandiVini. We'll wait for you at our table, Michele Scienza and Annalisa Motta, as usual.

Thre will be the current vintages of our wine, plus these news:

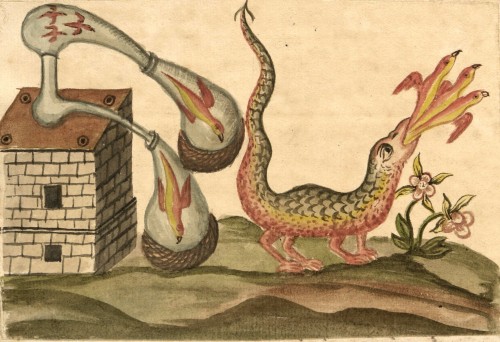

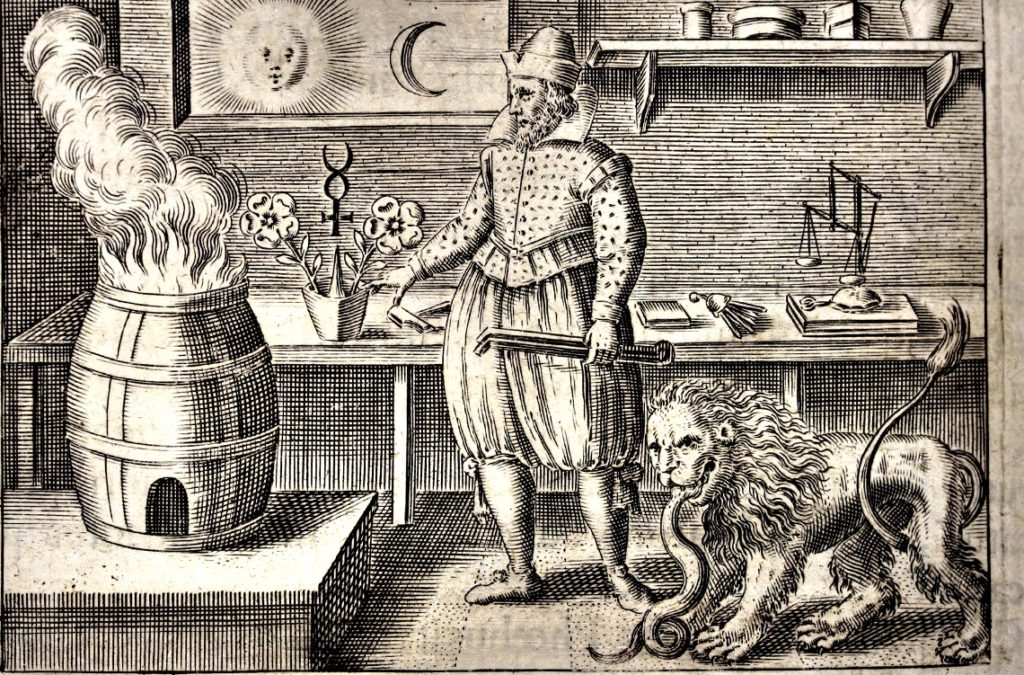

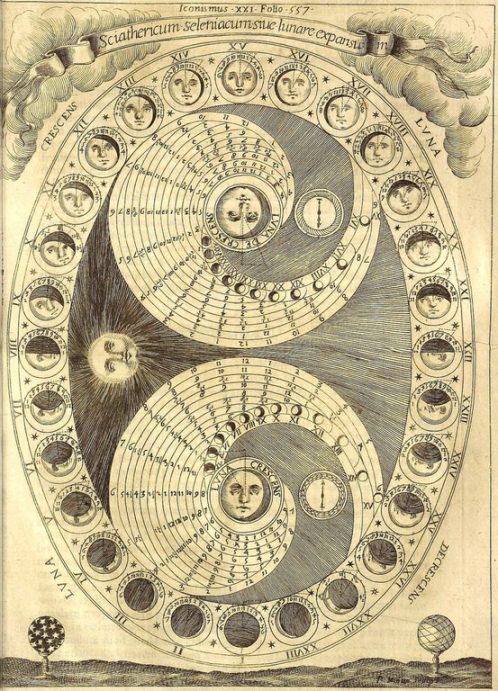

Fermentation in history 2: “It is rarefied to Spirit”

First interpretations on the fermentation process itself appear only in the era of alchemists-scientists, the seventeenth century. It is the historical moment in which the investigation of the world becomes more profound, though still mixing irrational aspects with burning science.

The understanding of this process began with the observation that a substance is formed by fermentation: alcohol (even if it was not called that at the time). The identification of this substance has its roots in distillation and alchemy.

The oldest stills date back to the 2nd century BC, found in Mesopotamia and in Egypt. In ancient times they were used only to produce essences for perfumed balms or for medical purposes. The distillation of alcohol, to produce hydroalcoholic solutions, probably began with the Arab alchemists Rhazes (Abū Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariyyā al-Rāzī) and Avicenna (Ibn Sīnā) between the 10th and 11th centuries. This knowledge was collected and disseminated in the West especially by the Schola Medica Salernitana, from the tenth century onwards.

In the thirteenth century the German philosopher and bishop Albertus Magnus describes in his works the substance "aqua ardens" obtained from the distillation of wine, so light to float on oil. Aqua ardens, burning water, and spirit of wine are among the most used terms for centuries to indicate alcohol or a more or less concentrated hydroalcoholic solution. Spirit derives from the Latin "spiritus" which means breath, vital spirit and, by extension, exhalation. The word alcohol will come later. Alcoholic beverages were indicated in this period with the generic term of aqua vitae (water of life), whatever the starting material.

The first work that describes in detail how to produce aqua vitae (with a double fermentation system) is a part of the Vatican code Consilia (1276). It is by the Florentine doctor Taddeo Alderotti, one of the most famous of his time, also mentioned in Paradise by Dante (12:82-85). I

Initially distillation of aqua vitae was carried out only in monasteries but, within a century, became increasingly popular. It was widespread mainly thanks to the treaty of the Paduan doctor Giovanni Michele Savonarola (1385-1468), the "De conficienda Aqua Vitae", which explained how to prepare it (he is the grandfather of the famous Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola).

Then by empirical distillation practice, increasingly perfected, it was born the identification of the substance that characterizes the wine from the grape-juice. Based on this knowledge, in the seventeenth century, we find the first attempts to interpret fermentation.

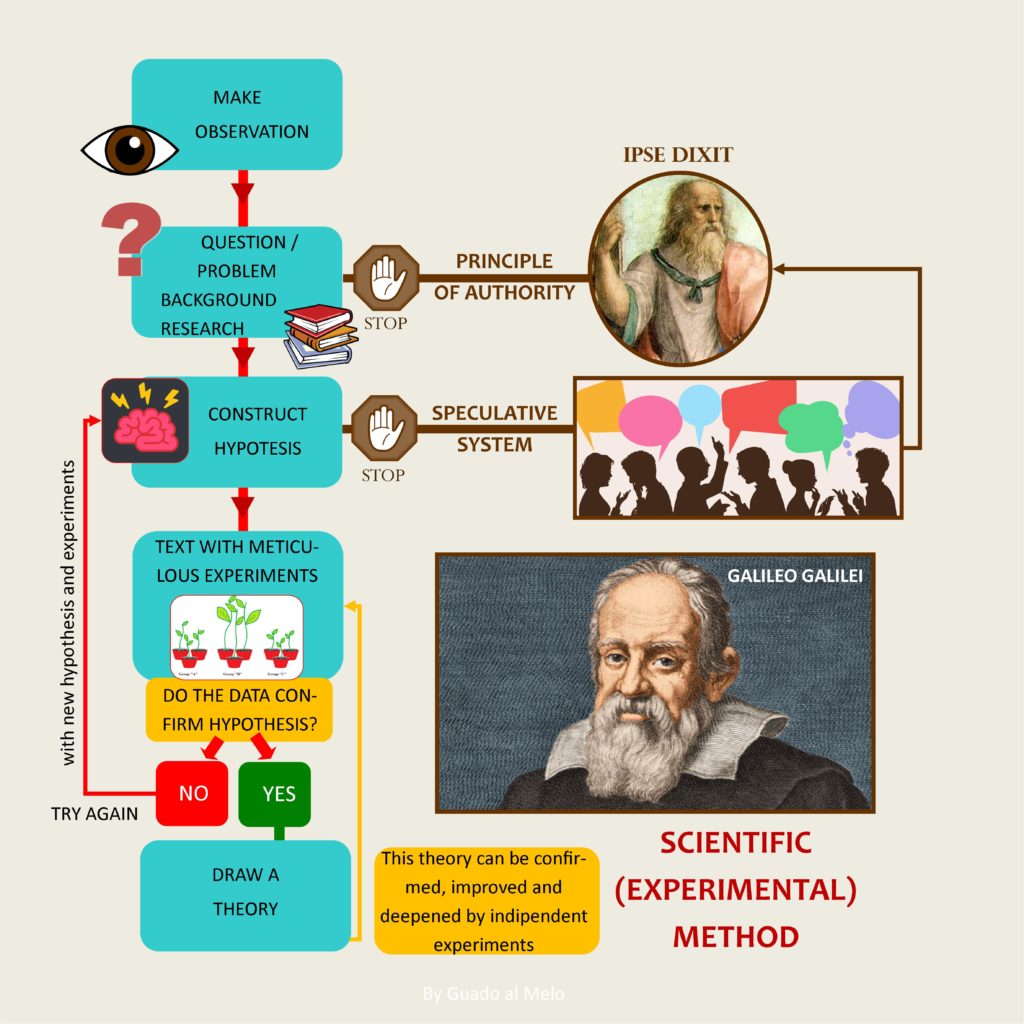

The seventeenth century is an era that represents a important break in the history of humanity and science, thanks to the birth of the experimental method. This will allow to overcome the principle of authority over time and to abandon gradually the mystical and magical aspects of alchemy.

Naturally it was not a clean break. For a few more centuries science remained in a middle world, poised between rationality and magical thought, with different figures of cutting-edge scientists and many still linked to the past. Even those scientists, which we remember today for important discoveries, still maintained (to a greater or lesser extent) some magical or irrational aspects.

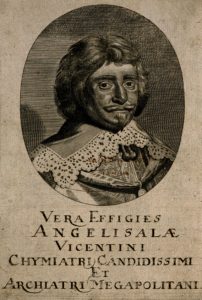

Returning to our topic, at the end of the sixteenth century the physician and chemist Angelo Sala (1576 - 1637) made the first studies on the formation of alcohol from fermenting musts.

Shortly afterwards the Flemish doctor and philosopher Johannes Baptiste van Helmont (1580-1644), disciple (and critic) of Paracelsus, admirer of the new experimental method, was among the first to hypothesize that fermentation was a chemical process, mediated by not well specified intermediaries. For van Helmont (and others of his time) reality consists of "minima naturalia", very small elements, corpuscles at the base of all matter. Chemical reactions, which he call indistinctly "fermentations" or "effervescences", are additions or subtractions of these particles. At the basis of the reactions there is a spiritual principle that operates through "ferments", unidentified mediators.

In addition to this, van Helmont identified that the gas released during fermentation is the same that is obtained by burning coal, at the time called “gas silvestre”, sylvan gas (because it derives from the combustion of plant matter). Today we call it carbon dioxide.

Another exponent of this world in the balance between nascent science and alchemy is Nicolas Lémery (1645-1715), French chemist who, in the second half of the seventeenth century, considered five substances at the base of nature: Water, Spirit, Oil, Salt and Earth. His work "Course of Chemistry" (1687) was a great success and was long considered a reference text. we can find in it a detailed explanation of the process of alcoholic fermentation.

According to Lémey, vinification consists in the transformation of a part of the must (Oil) into alcohol (Spirit), thanks to an action of "rarefaction" by the Acid Salts.

For Oil he means the part that remains non-distillable, while the Spirit is the part that can be distilled and flammable. For Salts he means both those that remain encrusted on the walls of the barrels (tartaric acid) and those that precipitate on the bottom at the end of the vinification.

Lémery, with his language (sometimes obscure for us), begins to identify different elements present in the juice and in the wine, even if with wrong roles in fermentation. This explanation, however, will remain for a long time as a model. In fact we find it (much the same) in the "Dictionary of Chemistry" by Pierre Joseph Macquer of 1766.

In addition to this, however, he reasons that wine no longer has the sweet taste of juice. Furthermore, he says, fermentation takes place more easily and produces more spirit substance if grapes are ripe. The unripe and ripe grapes change in flavor: the first is more acidic and not sweet at all, the other is very sugary. Therefore he concludes that the ripening of grapes (and other fruit) consists in the accumulation of sugars, which become dominant. From here he deduces that the material that undergoes alcoholic fermentation is precisely sugar.

Macquer continues by explaining some traditional practices to increase the sugar in the grapes by concentrating them by drying. He also mentions the practice of adding sugar directly to the must. He also points out that as early as the beginning of the century the Dutch doctor Herman Boerhaave (1668-1738) indicated that sugar is an effective means of promoting fermentation. The practice of sugaring was then widespread among the French wine producers in the early decades of the nineteenth century, thanks above all to the chemist Jean-Antoine Chaptal (wine sugaring in French is called "chaptalisation").

He writes, however, why it happen is still unknown and not easy to discover.

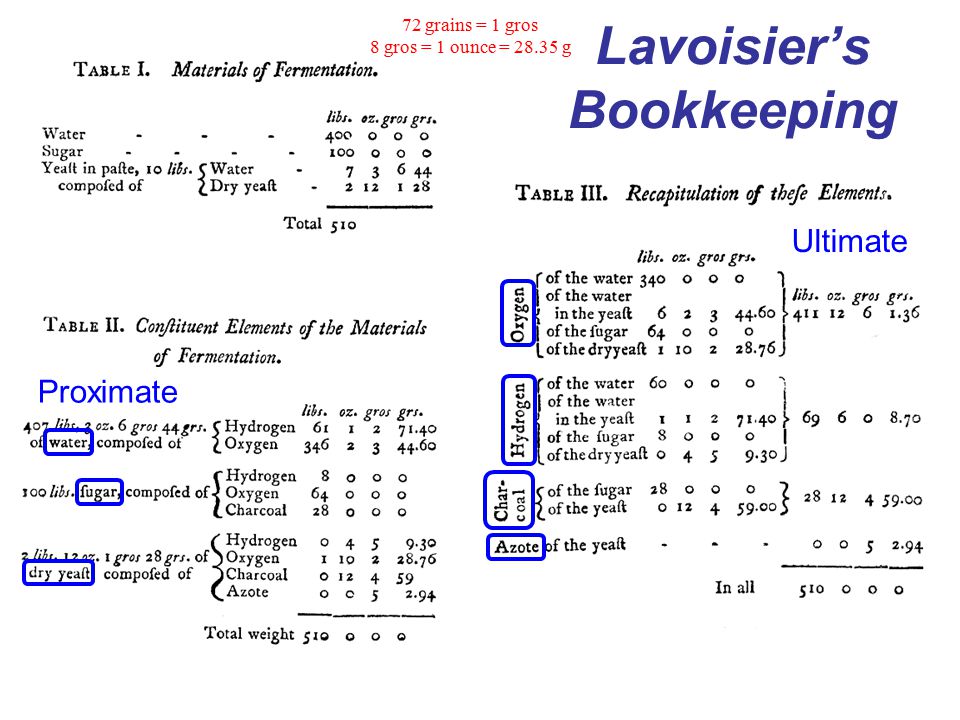

The first to describe clearly what happens during fermentation was Antoine-Laurent de Lavoiser (1743-1794) in his “Elementary chemistry treatise" of 1789. Lavoisier is one of those figures who changed history. He is recognized as the "father of modern chemistry" who, thanks to him, completely detached himself from alchemy.

Lavoisier begins to use the word alcohol and no more spirit of wine. In fact, he thought this term was not adequate because this substance could be formed not only from wine, but also from cider or sugar.

The word alcohol comes from the Arabic al-ko-ol. Originally it referred to the fine and black powder that women used to make up their eyes. From here, in Arabian alchemy, it was used to refer to any very fine powdered compound and so it also passed into the Western Middle Ages. It was then used to indicate the purest essence of a substance. It seems that the first to use the word alcohol in the modern sense was Paracelsus (Theopharst Bombast von Hohenheim, 1493-1541), the best known alchemist of his time. Lavoisier introduced it, however, into the common scientific use. In fact he is also remembered for his important reform of the nomenclature of chemical substances, at the base of the modern one. He wanted to go from the obscure and vague terms of alchemical origin to others, more concise and rational ones.

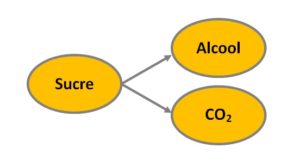

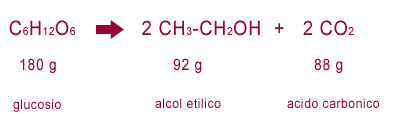

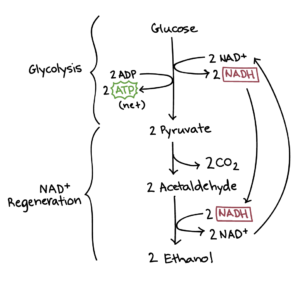

Returning to fermentation, Lavoiser, based on the knowledge accumulated up to his time, described it roughly as:

grape juice = carbonic acid (carbon dioxide) + alcohol

He experimentally reproduced the process with sugar dissolved in lukewarm water, to then estimate in a very precise way the quantities of fermented substances and the products obtained, also determining their composition. He was the first to write a chemical reaction as an equation. The measures were not exactly precise (given also the limits of the instruments of the time) but it was a real revolution for chemistry.

He described how the sugar split into two parts, and that the fermentation consisted in the oxygenation of one of them, with the formation of a combustible substance, alcohol. He showed that the transformation was not quantitatively exact because other secondary products are also formed.

The formula of the reaction was then defined quantitatively more precisely in 1810 by the French chemist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (1778-1850), thanks to the further improvement of the measuring instruments.

Then the chemists more and more refined the knowledge on the reaction, coming to define it with extreme precision. Today it is schematized as follows.

To get to this formula, however, still lacks a fundamental passage: at the time of Lavoisier there wasn't still organic chemistry!

In fact, nobody has yet respond to that fundamental question that we have taken with us on this journey through the centuries: who does it and why?

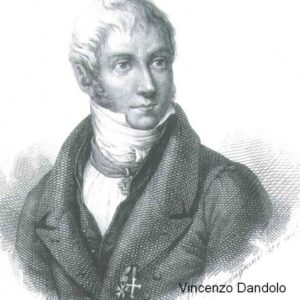

This question also arose spontaneously by Vincenzo Dandolo, an Italian (contemporary) translator of the works of Lavoisier who, in addition to translating, also made numerous annotations to the text. Lavoisier in fact, describing his experiments, tells about using brewer's yeast. Dandolo notes that the latter is formed by the sediment of the beer. He says that the fermentation is not well determined. He asks "why, how does brewer's yeast work? ... So the yeast becomes essential substance to make a complete fermentation, but though there are water, heat and sugar ".

So was yeast already known? No, this term is used to indicate something to facilitate fermentation empirically . Even from the ancient times, it was seen that by adding sediments of fermentation (or a bit of leavened bread dough in the case of bread making) the process started with greater ease. However, at the end of the eighteenth century, although having generally defined what happens, there was still no idea why.

Dandolo asks again: "What fermenting principle introduces this substance, or any other suitable to promote this first notable alteration ...? Would this phenomenon refer to the nitrogen that the yeast  contains? If so, how does nitrogen work? "

contains? If so, how does nitrogen work? "

He says that the yeasts traditionally used are of two species:

- "highly putrescible bodies containing nitrogen" (he write how some facilitate fermentation by throwing pieces of meat into the vat; he also tells how the Chinese add excrement to stimulate the fermentation of a decoction of oats and barley .

- "Bodies that contain a lot of oxygen like acids, neutral salts, clay, metal oxides, etc."

Beyond these aneducts and theories, for many at the time (as for the same Dandolo) "yeast" was some chemical compound. Only Pasteur, in the second half of the nineteenth century, put an end to this long diatribe, identifying it in a living organism.

However, Pasteur's work was not born from nothing and it was a very difficult and very controversial goal.

(to be continued…)

Next Wine Events

Here there are the next appointments where you can meet us and tasting our wines.

ProWein, in Duesseldorf (DE), 18-20 March 2018. Halle 16 / C22. C/o our importer Consiglio Vini.

Vinitaly, in Verona (I), 15-18 April 2018. Pav. 7 / Stand B5. C/0 our italian distributor Cuzziol GrandiVini.

Mostra Mercato dei Vignaioli FIVI, in Rome (I), 19-20 May 2018. Teatro 10, Cinecittà. Opening hours: 11.00-19.00. https://www.fivi.it/mercato-roma-2018-fivi-cinecitta-va-scena-territorio/

Fermentation in history 1: "It boils by its nature!"

After the post about fermentation, especially on the role of yeasts, I invite you on a little journey through history, to discover what people thought in the past about this crucial passage and how mankind came to understand it.

Fermentation has been used by man for at least 10,000 years for the production of beverages and foods: wine, beer, bread, yoghurt, cheese ... However, for millennia, humanity has done it without knowing how and why.

The word fermentation is ancient, derives from the Latin fermentum, from the root of the verb fervere which means to move, to boil. It arises from the observation of what is clearly visible: the bread leaven, swell and expand, the wine (or beer) boils.

But what did people think in the past of this phenomenon?

If we look for references in agrarian texts, from antiquity to the nineteenth century we don’t try hypothesis or questions about why and how it happens. Rather there are indications of practical work, useful to favor the process. This is natural: the agrarian texts in the past were mostly aimed at workers (of a certain rank), in particular the farmers. In the most ancient ages the problem is completely ignored (at least, as far as we know). In the texts of the Seven-Nineteenth century the whole process is cleared with the little phrase: "(the grape-juice) boils by its nature". So, it just happens, we're not asking why! These questions were left more to the philosophers and then to the scientists, but we will meet them later.

One of the most detailed agrarian texts of antiquity is the De re rustica by Columella (65 AD), "On Agriculture", which collects the sum of all the Roman agricultural knowledge. It is a text so well done and precise that it is considered by experts to be the first real agronomic treatise in history. It was so important that it remained the main reference for agronomy until the eighteenth century!

Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella lived in the 1st century AD, originally from Cadiz (present-day Spain). After a first military career in Syria, he retired to agricultural life in his estates in central Italy. He recounts that he was influenced in his interest in agriculture by his uncle, Marcus Columella, whom he describes as a cunning man and a great farmer. So his writings are not just a literary work (like other texts on agriculture at the time) but derive from direct experience, as well as from a curious mind that already appears very scientific.

Columella loves the agricultural life that he considers morally healthier than that of the city, as he tells in his work. According to him the farmer must directly manage his own farm and must have an excellent preparation on his work, based on the study of valid texts. It shows a particular sensitivity (compared to its times) on the use of servile labor.

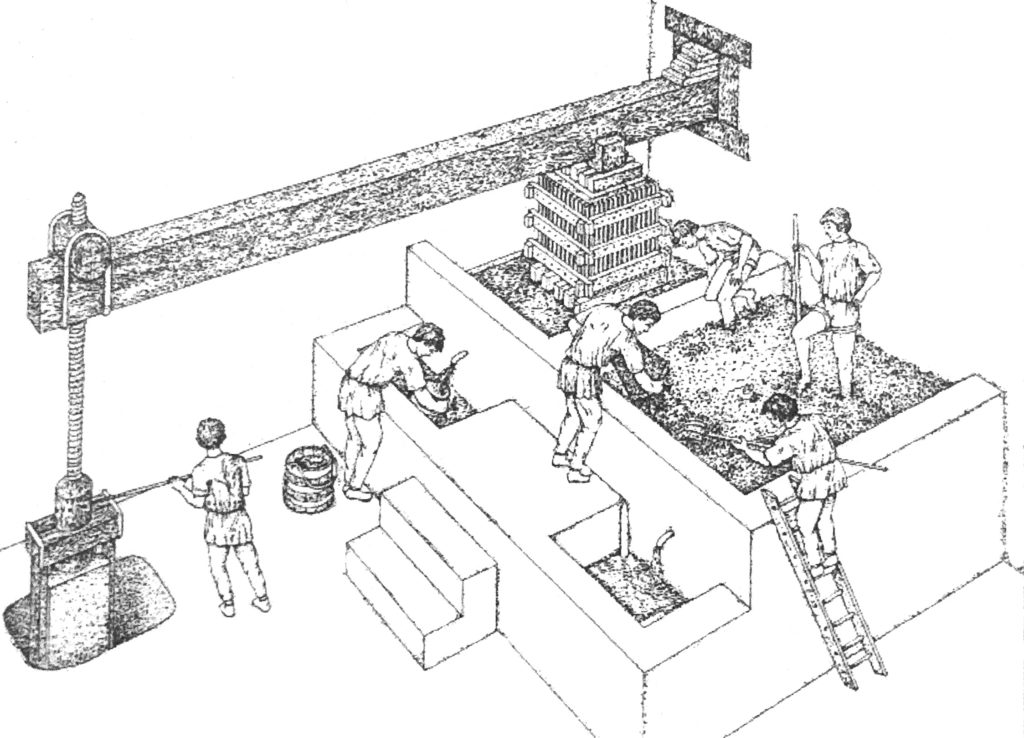

In the parts of the work dedicated to winemaking (much smaller than the space offered on the vineyard works part), we discover that Columella don't explain what happens in the fermenting dolium (pl. dolia: the terracotta pot used to make wine). Yet he gives many sensible advice (in light of our current knowledge) on how to work to ensure the successful of fermentation. In particular, he insists on the necessity of absolute cleaning of the cellar and of the work tools, above all of the containers where the juice and the wine will be placed. In fact, today we know that hygiene is the first fundamental requirement for producing a good wine, to avoid polluting it with micro-organisms responsible for many serious problems, as acetification, bad smells, turbidity, etc.

Columella remembers (as every good wine cellarer does today) that the preparation for the harvest must start at least a month before, with the thorough cleaning of each tool. Also he remember that the wine press must be well cleaned after each use. "The cellar must be cleansed from all grime, perfuming it with good smells, so that it is not offended by stinking or sour smell”.

The dolia (large earthenware vases in which vinification takes place), underground or not, must be cleaned and prepared by scraping the inner pitch layer of the previous year, after having softened it with heat, and then carefully spreading again.

The following advices mainly concerns indications of "condiments" to be added to the wine (resin, sea water, etc.) for the conservation of wine. I recall that, in any case, the wines of antiquity were very different from those of today. The problems of winemaking produced wines with tastes that today we consider defects. The common use of serving them mixed with water, aromas, spices, honey and much more just served to cover and correct these inevitable problems.

We know from more literal sources that in the ancient period it was common to attract good fortune on the harvest with augural rituals. In particular the Vinalia Rustica are celebrated on August 19th, i.e. auspicious rites for the next harvest (very similar to the blessings of the vineyards and fields that our priests did until a short time ago). Cicero, in "De Devinatione" cites the auguratio vineta, auspicious practices that traces back to the augur Attius Navius, at the time of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus.

We can’t help but imagine that even the delicate phase of fermentation had its share of rituals. And yet Columella does not tell us much in this sense, hinting only rapidly at the sacrifice due to Liber and Libera, to whom the fermenting vats are to be consecrated. For him, who seems to be a curious and very rational agronomist, it is more important that "we do not go away during the harvest from the wine press or from the cellar, so that juice is clean and pure ...".

If we go to the Middle Ages, the situation does not change much. As in the late empire, there are no longer terracotta pots, but wood predominates in the cellars. However, winemaking techniques are practically the same, sometimes even with poorer techniques, especially in the early Middle Ages.

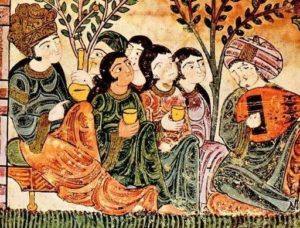

The greatest texts of medieval agronomy are above all those from Arab culture. Between the VIII and XIV centuries there is a great attention to agriculture: we count about fifty works dedicated to this field. These works flourish in all the lands under the Arab influence, in particular al-Andalus, the current Andalusia (Spain), which had a golden age in that period. For the Arab culture of the time, agriculture is a profession that requires specific knowledge. Some Andalusian texts reports agriculture as a profession (san 'a), but also as a science ('ilm) and an art (fann). In the work of al-Tignārī ("Book of the splendor of the garden and the delight of the mind") it is written: “anyone who has the aptitude, has the duty to devote himself to learning the science he needs to practice his profession. Those who are deprived of this attitude, must instead resort to the advice of the wise for everything related to their crops or the products of other trades”.

Unfortunately these texts do not speak us about wine, as it is already the Muslim era. However, they dedicate large parts to the cultivation of grapes, especially for fresh or dried consumption. Their sources are different depending on the works: some draw inspiration from classical Roman texts (above all Pliny and Columella), others from the Byzantines or ancient Mesopotamian operas. However we know, from historical and literary sources, that wine production in the viticultural territories had continued even after the passage under Arab rule. Mostly (and officially) it was carried out by communities of other religions and a small part for pharmaceutical purposes. In reality there was also a production of people of Muslim religion. The important thing was that it was not ostentatious. We know their winemaking techniques by other ways, but without sufficient details about our basic theme, fermentation. On this very interesting chapter, we will return in a next post.

Returning to the West, the only agrarian text of a certain importance is the "Ruralium Commodorum Books XII" of the Bolognese Pietro De Crescenzi (1305), based for many parts on the Latin writings, above all Columella. De Crescenzi also describes very well the phases prior to winemaking, such as the decision of the time of the harvest and the importance of cleaning the cellar, and then the subsequent ones (conservation). It does not mention the fermentation itself, but he explain how to try to remove the defects due to alterations.

In general the author abounds with empirical advice, sometimes reasonable for us (sometimes not). In the most difficult phases, such as the alterations of the wine, which seem to go beyond the human understanding of the time, arriving as terrible as inevitable fatal events, magical and superstitious aspects increase. These parts (that will serve me as a link to talk about superstitions in winemaking), were certainly already present in the Roman agricultural world and will remain for centuries until almost to our days. Middle Ages wasn't a darker period of many others!

But, why is wine altered? So the author explains it, in a rather obscure way (I did not find a translation in English and it is not easy to do for his archaic language and the unclear meaning of this sentence; so, it is a very free translation): "Due to its corruptible watery nature on the vine or in the vat, wine is corrupted and gone off by various causes as the strange heat. If you take off a little dregs or wine with sediment, put it in the container and then don't open it. It would turn into mold, which infects wine. In addition to this, every other wine placed there is spoiled. And if this wine is put in a dolium and mixes with other wine, it infects it and converts it into its corrupt nature." We know that the alterations of wine are caused by microorganisms, by oxidation or, on the lees , also for reductive phenomena. The author, obviously without knowing why, understands that it is something that happens inside, above all when wine stay long on the dregs. His considerations on the fact of not infecting a good wine with one gone bad are also important.

Again: "In addition, if you put the good wine, powerful and very sweet and body, during hot weather in a non-full and not closed tank, heat and damp evaporate, cold and the dry remain and wine becomes vinegar". The vinegar taste, which (as we know) derives above all from the action of acetic bacteria, for the author is a physical phenomenon (and unclear). However, he correctly understands the danger to let a tank open and not-full (causing contact with oxygen which, we know, facilitates the development of acetic bacteria). So, he suggests the best working methods.

"Wine dà la volta (may be "tourne" disease? It is a bacterial alteration of the wine, very common in the past) and it is more easily corrupted when there is the sunset of Pleiades, in the summer solstice, in the heat of the Dog (a constellation), when it is too hot or too much frost, during the great rains, in too many winds, for earthquakes, for thunders, when roses or vines bloom ". Practically, wine alteration can occur to every particular event that "disturbs" in some way the vinification. Some listed aspects are certainly true: changes in temperature can affect what happens in the tanks. A little less other events.

This belief, regarding the fact that certain events may disturb the winemaking, are found in many rural cultures of the past, in different parts of the world (both for wine and for beer). The popular imagination has contributed to the birth of a rich and extensive casuistry, mixing intuitions of real facts (better to avoid the sudden changes in temperature) to fantastic events.

At the base is the idea that something is happening (people can see and hear it !) But is incomprehensible. Instinct leads to reverence: perhaps, if nothing disturbing happens, everything can go well... What happens, who acts? Spirits, demons, magical entities? Something is operating and so it's forbidden to make noise, its better walking slowly, whispering, it's forbidden to knock on the vats or barrels, to let doors or windows open , ... Every territory has his stories about it. Superstition also generates terrible warnings to prevent inappropriately behavior: if a person knocks on a vat or a barrel, thus making the wine bad, he risks losing his finger or hand. It was also believed that the cellar should be kept closed to prevent evil spirits or witches or black cats from negatively influencing the process. Many other situations could be bad, like women with menstruation, who must not approach the vats. According to some peasant cultures the outcome of winemaking also is a premonitory sign of the family's destinies. If it is not good, troubles are coming, if there are serious alterations, there could be misfortunes.

But returning to De Crescenzi, what are the remedies for the alterations of the wine? Here there is a very long list. Some practices described to prevent problems (or solve them in the early stages) are adequate, such as wine racking or keeping vats well filled and closed. When the damage is done (and even today it is almost impossible to remedy) the author lists instead a little more imaginative interventions, such as various kinds of concoctions to add to the wine, based on herbs or other. Certainly these don't change the destiny of wine, as the author suggests, but perhaps they are more useful to cover bad smells or tastes (in the medieval period, as in the antiquity, it is a common use the correction of wines with spices, herbs, honey or other). It is also suggested the use of “magical” plants, such as the Clematis vitalba (old man's beard) which, if placed at the base or above the cask, should prevent the wine from altering. The most curious is a sort of propitiatory rite linked to the religious sphere: an apple must be placed in the container, with a rolled-up leaflet in it: "GVSTATE ET VIDETE QVONIAM CHRISTVS SVAVIS EST DOMINVS". (Taste and see that Christ the Lord is good).

Of the beliefs mentioned by De Crescenzo, the most widespread, the most fascinating and one of the hardest to die, is the one that binds the wine to the lunar phases. According to the author, the harvest must be done during the waning moon, while the decanting with a crescent moon, otherwise the wine becomes vinegar. For example, 500 years later we find the same beliefs, as Gaetano Cantoni reported in his "Complete Agriculture Treaty" (1855) : "According to some, the moon would also influence the fermentation of manure, and consequently the dunghill should rather be turned around in the last days of the moon, because in this period less quantity of useful ingredients would dispersed, and they would remain ordered for fermentation, favored by the first quarters of the following moon. The same thing would happen for wine fermentation: about it there are the proverb that the wine made in two moons is clarified with difficulty or never ". This belief has remained until almost our days in rural culture (and not only).

These beliefs derive from the magical thought that anthropologicals have called "sympathetic magic". One of its most important principles is that of similarity. It is based on a banal mental association whereby the similar calls the similar or where something that symbolizes a certain action has influence on it. In this conception the crescent moon is bound to all those actions or situations in which there is something that grows or has to develop or move. Instead the waning moon assumes a link with everything that decreases, which must stop or die. Therefore all the phases of agricultural harvest that involve the cutting, the death of the plant or the crushing (as for the grape), must be done in the waning moon. Instead, an action like the pouring, a movement, must be done in the crescent moon.

However, there is no need to go too far in time, these beliefs are still alive today. Magical thinking is subtle and powerful. Sometimes it is not possible to avoid it even through culture or centuries of research and scientific discoveries. The spontaneous question is: why have these beliefs survived for so long?

We must think, as described in the medieval text, that in the production of wine the magic-superstitious rituals are never done alone. They are always accompanied by good empirical practices that can lead to positive outcomes. Here, however, humanity is divided into two categories. People with a rational mind tend to think that it was good work that produced good results and focused on that. From this mental setting, over the centuries science was born. Other people instead are brought to focus their attention more on the fact that the magic has worked. Furthermore, often people makes talismanic gesture, thinking "it doesn't hurt"! And so these beliefs are perpetuated over the centuries.

And with our knowledge of the last centuries? It seems absurd, but for some it may be easier to make sense of the simple mental correlations required by magical similitude rather than to understand the chemical or physical or physiological concepts behind certain good work practices. And then, the most important consideration of all: we like these stories!

They are beautiful, poetic, they use evocative images and words. These stories are fascinating and seductive. Also for this reason, over the centuries they have conquered and continue to this day, becoming also powerful marketing strategies of some sellers (more astute or more naive?) .

After this digression into the superstitions surrounding the winemaking, we arrive at the age of the alchemists. Thus we discover that here begin to appear the first interpretations of the real fermentation process.

(to be continued ....)