“I have been in Maremma for a long time. There is not even a wolf anymore. Where those poor animals came in droves in the evening, howling, now yellow vines bloom and the boys play the mandolin. The old secular oaks were cut down, years have passed, and everywhere there are olive trees, wheat and vegetable gardens. You can see the dark green of the woods only in the high hills; and some old boar, bored by the world, retires there … No more buffaloes. It’s a sin. Something is missing.

But the wine is a lot and it is very good!”.

This is a letter that the poet Giosuè Carducci wrote on October 26 1894, telling about one of his trips to Castagneto and Bolgheri, the lands of his childhood. In these few lines, he makes a perfect synthesis of the change in the territory that took place during the nineteenth century: from a wild area, it has become an agricultural one, where a very good wine is produced. Are you ready to find out it?

Windy vineyards, Carducci and Barbaric Odes: as Paolo Conte sings (in Italian and Spanish) in “Cuanta Passion“:

“… Le vigne stanno immobili / nel vento forsennato / Il luogo sembra arido / e a gerbido lasciato / Ma il vino spara fulmini / e barbariche orazioni / che fan sentire il gusto / delle alte perfezioni …. (The vines stand still / in the frenzied wind / The place seems arid / and uncultivated / But the wine shoots lightning / and barbaric prayers / that make you feel the taste / of high perfections …)

Cuanta pasiòn en la vida / Cuanta pasiòn / Es una historia infinita / Cuanta pasiòn / Una illusiòn temeraria / Un indiscreto final / Ay, que vision pasionaria / Trascendental! … (How much passion in life / How much passion / It is an infinite story / How much passion / A reckless illusion / An indiscreet ending / Oh, what a passionate vision / Transcendental!)

(Paolo Conte, “Cuanta Passion“)

We are continuing our journey in the lesser known history of the Bolgheri DOC, our small Tuscan wine appellation, located in the municipality of Castagneto Carducci (Carducci, in honor of the poet, of course). We have already seen how here, in Etruscan land, the viticulture was born in an autochthonous way, starting from the wild vines of the woods made domestic (here). We learned about the traditional Italian training form of the vine “married” to the tree, born in the Etruscan-Roman culture and never disappeared until about the mid-twentieth century (here and here). We have seen how, especially in Roman times, ours was a flourishing agricultural territory, wine producer, at the center of a network of European trades (here and here). We have seen how a difficult phase followed (here), when the Maremma becoming harsh and wild, but the wine resisted, even if only for subsistence.

The nineteenth century was the century of the rebirth of our area. The territory returned to having a flourishing agriculture, completing the transformation slowly begun in the previous centuries. Above all, the wine production increased, as I’m going to tell you.

The transformation took place thanks to the reclamation works begun at the end of the eighteenth century. The Maremma, from a forgotten and exploited land, had now become the “great sick” to be healed in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, thanks to the new sensitivity born in the Century of Enlightenment. The definition of Maremma at the time was not strictly geographical, but socio-economic. It included all those territories of Tuscany characterized by “little agriculture, massive extension of woods and marshes, scarce population” (Carlo Martelli, 1846). Our part of Maremma, called at the time “Pisana” (of Pisa; the current province of Livorno will be established in 1925) was the first to complete the transformation and move up a category.

The disparity between the different parts of Tuscany was enormous and the common thought about Maremma was divided between compassion and contempt. For example, the French agronomist Drédéric Lullin de Châteauvieux, who visited our lands in 1834, wrote that he felt like “sur la frontière du désert au de-la toute culture cesse” (“on the frontier of the desert beyond which the culture ends”). Beyon this border, extreme poverty, malaria and bandits continued to reign.

If this was the opinion of the time, you will understand why leaving the category of Maremma was seen as a victory, as evidenced by the politician Alfredo Beccarini in 1873. He wrote that the Maremma begins under San Vincenzo, as the northernmost territories were already reclaimed and occupied by farmers, to the point now “to despise the ancient and defamed name”.

The exodus from the hills

Before telling about wine, let’s see how the landscape of Bolgheri territory has transformed in general in this period. Between the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the actual structure begins to take shape, with the definitive shift of the focal point from the hills to the coastal flat.

The agricultural development therefore started from the hills and the foothill areas. The deforestation then extended to the plain area around Bolgheri. Then, it advanced in the rest of the plain, which began to be populated, in parallel with the water regulation works, which eliminated the marshy areas.

The occupation of the plain also required the creation of a better road system. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the via Aurelia was rebuilt, the ancient Roman consular road, by now plundered by stones and reduced to a path (or a little more). The new road was realized some meters towards the sea than the original route. The famous boulevard of Bolgheri, created in the late eighteenth century, was planted in 1831 with poplars. These trees were replanted several times because they were constantly damaged by the (last) buffaloes. In 1834, they began to be replaced with the cypresses, not so good for the buffaloes. At the time of child Carducci, who then made the cypress avenue famous with his nostalgic ode “Before San Guido“, the trees arrived halfway along the route. The tree-lined avenue was completed till Bolgheri after the poet’s death (1907), to pay homage to him and his famous ode.

The rall straigh cypresses in double row

troop from San Guido down to Bolgheri;

like giant striplings at a race they go

Bounding to meet and gaze once more me.

Straightway they knew me: “Welcome back again,”

Bending their heads to me they whispering say,

“Why dost thou not alight? Why not remain?

The evening’s coll, familiar the way,

“Oh, sit thee down beneath our odorous shade,

Where breathes the North-West wind from off the sea.

…

I have found the traslation here.

…

The definitive shift of the population towards the plain depended by the construction of the railway line, in 1863. The station was built next to a farm belonging to the della Gherardesca noble family. Around it will develop what is now the most populous village of the municipality, Donoratico. It takes its name from the ancient hilltop fortress (that I have already mentioned), abandoned for centuries.

While the foothills and the plain were being deforested, the forest returned to regain most of the hills, especially due to the abandonment of the pastures. In general, the colonization of the plain will have the effect of a real exodus of the population, who will increasingly abandon the hills to move towards the plain. The great extension of the hilly woods, that we can still see today derives, for the most part, from natural reforestation phenomena, which occurred in the last hundred / one hundred and fifty years.

The wood widened but at the same time it ended its ancestral relationship with the local people. For millennia, it had been at the center of a large part of the local economy and life, with the harvesting of chestnuts and much more. It was populated by charcoal burners, woodcutters, gatherers, pigs that grazed in the wild. Today it is a wild and empty forest, if not for the shooting of hunters and companies specializing in cutting wood.

The deforestation of the plain caused deleterious effects on the environment. Thus, in 1837, the planting of the coastal pine forest began, above all to act as a barrier to the wind and sand, to protect the cultivated fields. The railway made transport by sea disappear and thus permanently closed the Customs offices, located in the ancient fort on the beach (on the far right in the photo below). Close to it, in the 20s of the twentieth century, the first small group of villas was born in what would later become the seaside resort of Marina di Castagneto.

The great expansion of the wine, between tradition and modernity

On the nineteenth century, there was a fairly generalized boom in wine production throughout Italy (and in the rest of Europe). The production grew almost everywhere, driven by the significant increase in the population at the time, as well as by the progressive improvement of production techniques. The same happened in our Maremma Pisana, as told in the Tuscan Agricultural Journal of 1832, in the article “Corsa Agraria della Maremma” (“The rapid increase of agriculture of Maremma”) (here the full article):

“The main income items of a possession in Maremma are: 1 ° the cereals, 2 ° the wine, 3 ° the oil, 4 ° the cattle, 5 ° the woods. …

The cultivation of the vine spreads for every where in Maremma … ”

As reported in the piece, the vineyards in Maremma increased a lot because the wine production was no longer able to fully satisfy the local request. The wines were already sold out before the summer. The article highlights the strengths and weaknesses of this production, more or less the usual problems of the time: the production of too many quantity of grapes, bad oenological techniques, especially that so called Tuscan “governo“, wine-cellars not suitable for the storage (especially for the temperature).

What is the Tuscan “governo“? How was the wine producted in Tuscany at the time? The “governo” was a winemaking practice useful to give more strength to poor and too light wines. They were frequent at the time, due to limited winegrowing and winemaking practices . It was not the only system: for example, it was common at the times to reinforce weak wines by adding a little grappa or other liqueurs, both in Italy and in France. Firstly, some healthy bunches were harvested separately, which would be used for the “governo“. These bunches were dried on racks or hung on hooks and wires in the cellar. The rest of the grapes were normally harvested and winemaked. Then, the wines were placed in wooden barrels. On November, the chosen bunches, now partially dried, were pressed and the fermentation was started. The “governo” was this mixture of very concentrate fermenting must and skins that the winemakers added to the casks (not completely filled at first) of the weaker wines (from 5 to 10%). The (relatively) low temperature of the period, the alcohol present and the little sugar caused a very slow fermentation, which lasted even a month. This practice enriched the wine with few degrees of alcohol and a some more scents. This wine was slightly sparkling, due to the carbon dioxide developed in the second fermentation. The “governo” wine was consumed young, leaked directly from the barrel.

The Tuscan Agrarian Journal is critical about this practice. Firstly, the producers often neglected the good care of the production due to the possibility to correct the wines with the “governo” practice. Secondly, the “governo” reinforced the wine but also originated several defects. The refermentation, carried out in conditions of poor hygiene and not always adequate temperature, often increased a lot the volatile acidity and many other defects. The subsequent improvement in winemaking techniques brought back the “governo“, which spread in Chianti, but also in other Italian regions. Later, it disappeared in Tuscany (today, it is enough our sun, with good practices, to produce great wines). Similar practice has remained in cooler Italian regions (as the “ripasso” in Veneto).

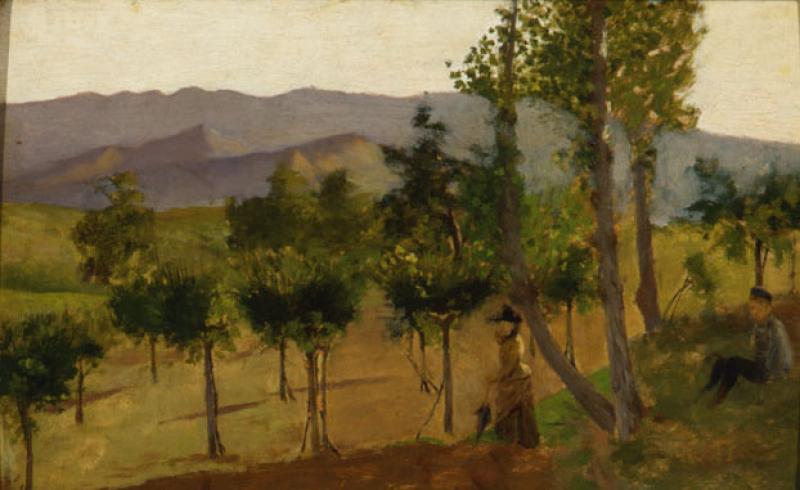

Now let’s talk specifically about our territory. A suggestive description of the agricultural landscape of that time is found in the Tuscan Agricultural Journal of 1832. The article tells of the visit to the territory by three exponents of the Georgofili Academy of Florence: Cosimo Ridolfi, Lapo de’ Ricci (agronomist, who signed the article) and Raffaello Lambruschini. The three guests visit Bolgheri, then they went to Castagneto, passing near the long Segalari Hill (see the map below).

Describing the vineyards of a noble family farm (Della Gherardesca) in the plain near Bolgheri, the piece tells that the vines are mainly supported by cane, broom or juniper poles, sometimes also by field maples (“loppi“, in the Tuscan of the time). There is a criticism of the fact that the rows are too narrow and the vines too dense, as well as other pungent observations. The farm manager, Giuseppe Mazzanti replies to the criticisms with a proud letter, published on December 15th, 1832. According to Mazzanti, the rows are not too narrow, being 24 “braccia” wide (about 14 meters) and allow the intermediate cultivation of rotation of wheat, broad beans and lupins. This is clearly a mixed cultivation.

The visiting group then goes to Castagneto. Passing in front of the Segalari hill, they are struck by the care of the crops, dominated by vines sustained by field maples, alternating with fields of forage and cereals. They praise them, without lacking a certain condescension:

“… the Segalari hill draws the passenger’s attention for its delightful cultivation. Small modernly built houses, fields planted with vines, and these leaned on field maples, flourishing vegetation of cereals and fodder, a certain care in the direction of the water and, we could say, a certain refinement that is not common in Maremma…”

The hill of Castagneto is described as steep, covered with vines and olive trees of remarkable vigor. After visiting the village and the castle, they descend towards the via Aurelia, crossing “arable land and vineyards“.

From this and other testimonies, we can understand that, at the time, the mixed viticulture dominated here, as in all Tuscany and central Italy, that is, rows of vines were cultivated alternating them with strips of wheat or other. This not means that grapes were a secondary production. Let us remember that Chianti, in those periods, exported wine all over the world producing it from vines supported by trees (vine “married” to the tree, it is the traditional Italian name), in mixed cultivation with wheat.

As we have understand from this testimony, at the time (as today and even more) our territory was dominated by the great estates of noble families. Each farm was divided into severl “poderi“. A “podere” is one little part of the estate, entrusted to a farmer family. On the other hand, around Castagneto and on the Segalari hill, due to the historical events that I mentioned here, there were numerous medium and small properties and there were much more buying and selling movements.

I tried to understand the dimension of local production at the time, but I found only very few data. They are also often affected by the modern prejudice of considering as vineyards only those with intensive cultivation (monoculture). Actually, the vast majority of the vineyards of that time was rapresented by the promiscuous viticulture, that was the local tradition since the Etruscan time. Excluding it means introducing a big error in the evaluations.

The University of Florence, under the guidance of Mauro Agnoletti, conducted studies starting from the analysis of data from the land registry of the time. Three historical moments have been examined: 1832, 1935 and 1954. I was amazed by the fact that they left a frightening hole in the middle (about 100 years), which includes precisely the period of maximum wine-growing expansion of the territory.

In 1832, which is still a moment of onset of agricultural development in the Maremma, the cultivated areas occupy 23.5% of our territory, with a prevalence of arable land. The study reports that the monoculture vineyard occupies about 35 ha (I remember that one hectare equals 10,000 square meters) and, curiously, it stops here, not considering that at the time intensive viticulture was the minority. So, I added up all the areas where the nineteenth-century cadastre explicitly reports the presence of vines with other crops, reaching over 360 ha, 1/4 of the cultivated areas. Of course it is not possible to compare the hectares of mixed viticulture with those of intensive, which we refer to with our modern models. However, we can understand that already in 1832 viticulture was very widespread in the area. I remember you that our territory is very small: the actual wine production is 1300 ha circa of vineyards.

The period of maximum growth of the farms took place in the following decades, with the birth of numerous vineyards, as evidenced in the books by Luciano Bezzini and Edoardo Scalzini, who examined the rich documentation left by the estates of that time. Unfortunately, there is a lack of overall data from this long and decisive period. Below, there is a sigle data, ase the below example.

In 1903, in the Farm Gherardesca of Castagneto, there were 750 ha of mixed viticulture and cereals, with the presence of 352,190 vines. There are also 22 ha of monoculture vines, of which 17.5 ha were dedicated to black varieties (with 144,514 vines) and 4.5 ha of white grapes (30,680 vines). Their density is comparable to the densest modern vineyards: over 8,000 vines per hectare in the first case and almost 7,000 in the second. If we divide the number of vines of promiscuous viticulture by this density, we can relate the mixed production to an intensive vineyard of about fifty hectares. In total, therefore, this single farm produced wine for an area comparable to about 72 hectares of dense vineyards.

The area planted with vines in 1935, according to the land registry study, is 301 ha, but again it only refers to intensive viticulture. This time there are no detailed data that allow me to calculate the mixed viticulture. There is only a generic “arable land with other trees” (which could include vines but not only) which occupies 1665.76 ha. However, we know that this is a period of decline in the area’s viticulture. From the 1920s, the phylloxera (remember? It is the parasite that threatened to wipe out world viticulture) damaged locally as never before, after a first appearance in 1895.

Prof Agnoletti attributes to the phylloxera the main cause of the dramatic decline that local viticulture underwent around the middle of the twentieth century. The cadastral data tell us that in 1954 intensive viticulture had dropped to just over 7 hectares. Again, the study neglects the promiscuous one, it does not even tell us whether it was still present or not, except that the generic “arable land with other trees” has expanded to 2276.76 ha.

We know for sure that the viticulture crisis of the time gave way to other crops. The first half of the twentieth century saw the boom of olive trees in monoculture, which had an increase of + 300% throughout the province of Livorno. In 1925 Mussolini started the “battle of wheat”, pushing towards the expansion of productivity and surfaces, which expanded as never before in Maremma. Fascism also stimulated the increase of houses scattered in the countryside, which had never been more numerous here. The fruit trees, such as the peach trees, and the horticultural crops also spread.

Stories of vineyards and farms

Let’s now see in detail how the production was at that time, from the examination of the documents of the estates of the area made by Bezzini and Scalzini.

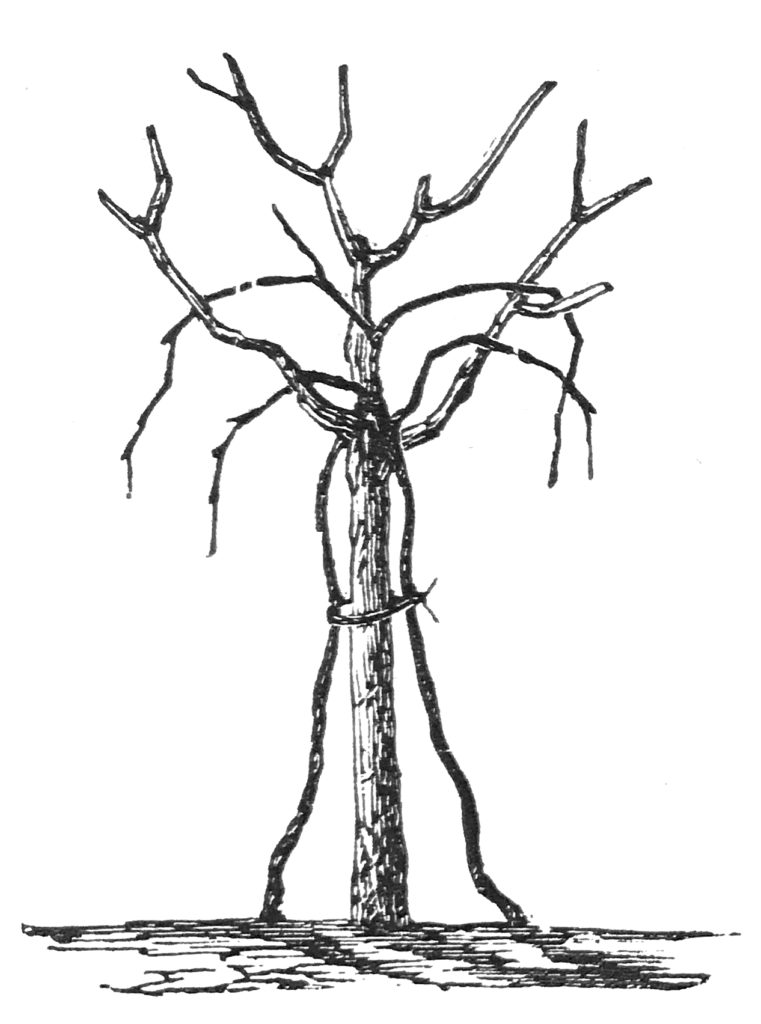

As we have seen, the vineyards were mostly made of vines “married” to trees, the ancient vine coltivation system of Etruscan-Roman origin that I have already talked about fro long. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, in Bolgheri, we often found the word “piantata“, a term that has also remained in some toponyms. In the old agronomic language, “piantata” indicated married vines that pass the shoots from tree to tree, forming rows. However, it was often used improperly (and vice versa) to indicate the “alberata“, i.e. the vines wrapped around a single tree. The local use of certain terms is not always easy to understand.

But we know with certainty that here, as in almost all of Tuscany and other central regions, the ancient Etruscan custom of field maples as supports remained. As wrote above, the tree was sometimes replaced by poles. I have personally seen still today in very rare old vineyards (see the photo below). Probably the version with poles was prevalent in the few monoculture vineyards at the time.

In the Tuscan agricultural texts of the time, the cultivation practices of the vine “married” to the tree are explained in detail. A reference text of the time is that of the botanist Saverio Manetti, entitled “Oenologia Toscana” (1773), published under the pseudonym of Giovanni Cosimo Villifranchi. He writes that the cultivation with the married vine allows to obtain excellent quality for the grapes and the wine, provided that this is set and managed in an optimal way, with the tree and the vine in an unexpanded form. Both of them were in fact kept low and adequately pruned. According to Manetti, but not only, the field maple is the best of many other trees, because it does not interfere with the optimal development of the vine: the roots take up little space and the crown can be easily contained with an appropriate pruning. This is the oldest form of agroecology.

The vineyards included, as was common at the time, several varieties. The wines were always born from a field blends. The main local varieties reported in the documents are Sangiovese, Vermentino, black Canaiolo, white Canaiolo, black Malvasia, white Malvasia, Tuscan Trebbiano, Aleatico, less common Mammolo and Pernicione (now disappeared). There are also French vines, often written with Italianized names, such as Gemè (Gamay), Carmené (Carmener or Cabernet franc), Caberné (Cabernet sauvignon), Scirà (Syrah). Mostly still wines were produced, especially reds (although sometimes white grapes were present in the blend), white ones in lesser quantities. There were basic and top wines. Sweet wines were also produced, especially made with Aleatico, and a slightly rosé vin santo, which is why it was called Occhio di Pernice (Partridge Eye). The production of white wines grew especially in the early decades of the twentieth century, due to the great market demand of the time. In this period, the arrival of Chardonnay, Clairette and Sémillon is also noted, as well as the first appearance of Merlot.

It was common at the time that the cellars were in the villages, especially as regards the small owners of Castagneto. You could smell the scent of wine during the fermentation in the streets of the villages, as told in the famous lyric of Carducci “San Martino” (Saint Martin’s Day). For those like me who live in Castagneto Carducci (or even just know it), I imagine easily this windy day of early November (on the Saint Martin’s day) while I’m looking from the top of the hilly village the stormy sea and the mist of the plain below.

The fog to the bare hills

soars in the thin rain,

and below the wind

howls and churns the sea;

yet through the hamlet’s alleys

from the fermenting casks

goes the pungent scent of wines

to touch a soul with glee.

On the firewood, turns

the skewer crackling:

stands the hunter whistling,

on the threshold to see

in the reddening clouds

flocks of black birds,

like exiled thoughts

as in the dusk they flee.

If fthe cellars were almost always inside the villages or the small owners, there were mixed situations for the large estates, with cellars in the village and even in the individual farmhouses. Usually, each farmer vinified his grapes separately and the wine was then taken by the estate owner for the part due to him. I found in only one case, at the time, the presence of a single centralized wine-cellar, in the Serristori estate (which was located in the southern part of the municipality).

Let’s go back to the article of the three Florentines visiting the territory in 1832, as they describe the wines tasted in Castagneto:

“The common wine is not very intense but it does not have a brackish taste like many Maremma wines, and it is pleasant. The wines made with more accuracy, “for the bottle”, are exquisite; the skill of the winemaker overcomes the quality of the grapes, or one conspires with the other. Aleatico and vin santo have a lot of grace and fragrance and are excellent; they are never too much sweet, nauseant, characteristics that displease all connoisseurs of local wines so much”.

These praises stand out particularly in the newspaper which, on the other hand, is generally very hypercritical about the wines of the Maremma Pisana.

My interest was particularly focused on the history of the old Espinassi Moratti Farm, because it also included the vineyards that today are those of our winery, Guado al Melo. The Morattis, then Espinassi Moratti, created and expanded their properties starting from the end of the eighteenth century, until to create a very large estate. Giovanni Moratti bought the land, that today form the vineyards of Guado al Melo, in an area then called “Campo al Lucchese”, on the first edges of the north side of the Segalari hill, in two times. In 1818, he bought a part from a small farmer, Giovacchino Balli, and in 1820 by the owner of the Segalari Farm, Giulio Bigazzi. In 1824 he also bought the neighboring “podere” Grattamacco from Bigazzi, where there was a farmhouse and formed a single large podere. The wine that was produced there managed to get high prices in the high society of Pisa, because it was “full-bodied and fragrant”. The success prompted the owner to take all the wine, including the part due to the farmer, giving him one of lesser value in exchange. The vines cultivated were the classic ones of the area already mentioned: Trebbiano, white and black Malvasia, Vermentino, white and black Canaiolo Bianco, Sangiovese, Cabernet sauvignon. In the twentieth century the prevalence of white varieties is reported, as well as the presence of Merlot. In the early years of the twentieth century, the farm experienced a period of crisis, but then flourished again in the 1930s. In 1925, the estate’s wine also won the first prize of the Rome Wine Fair. In 1937, the Grattamacco farm, judged too large for a single family of farmers, was divided in two. The Santa Maria farm was born, with the construction of a new farmhouse, at whose service the vineyards of today’s Guado al Melo remained. In the second post-war period, the estate began to be partially dismembered. In the 1960s, it yet included 22 hectares of specialized vineyards, among which the vineyard of Santa Maria is still mentioned, equal to 12 hectares, whose boundaries described are precisely those of Guado al Melo (between the Gelli’s mill and the Grattamacco dyke). The vineyards of today’s Guado al Melo were then sold, separated from the remaining Podere Santa Maria, to a local farmer who, as his sons told us, continued to produce wine.

“The wine is a lot and it is very good” and will have a great future

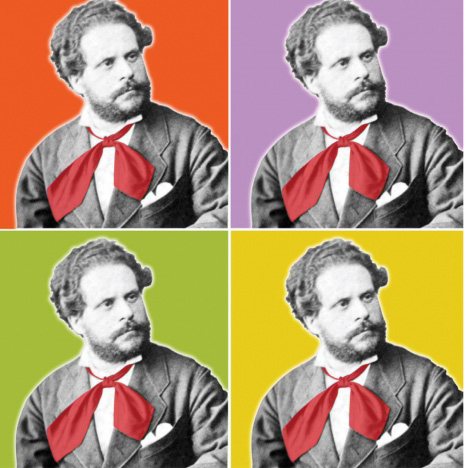

Finally, let’s go back to Giosuè Carducci, Nobel Prize for literature, with whom we began this little journey and with which we conclude it.

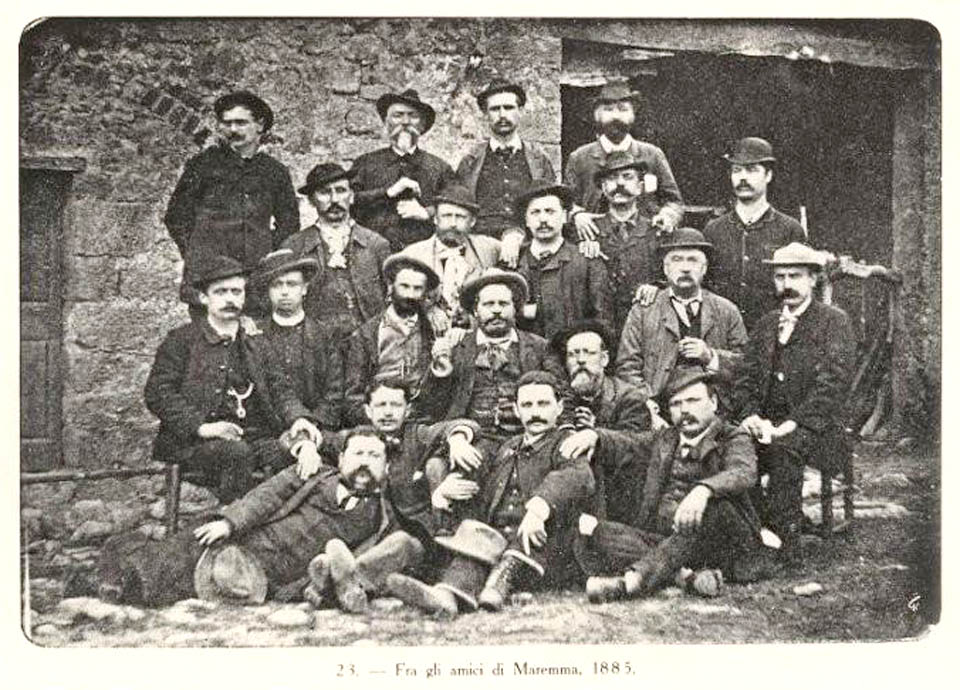

The poet celebrated our land in his lyrics, even if he was not a native of the place (he was born in Valdicastello, in Versilia, norther in the Tuscan coast). He arrived here with his family at the age of three, following his father (a doctor). He spent the carefree years of childhood and early adolescence there, first in Bolgheri and then in Castagneto, and this land remained imprinted in his heart. He had the local wine sent to Bologna, where he taught, and he also consumes it abundantly during his visits to his friends, dedicated to banquets with a lot of wine, which he called “ribotte” (blowouts).

Carducci is the emblem of the great boom of wine in Bolgheri (and Castagneto area) during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As mentioned, the phylloxera destroyed the local production, giving space to other crops. However, as we all know, it will only be a pause: then, a new rebirth of wine will begin, which will be more extraordinary than ever (in the next post).

Bibliography:

Agnoletti M, “Il Paesaggio come risorsa, Castagneto negli ultimi due secoli”, Ed. ETS, 2009

Agnoletti M., Paletti S., “Il ruolo del vigneto nel paesaggio di Castagneto Carducci fra l’Ottocento e l’attualità”, Facoltà di Agraria, Università di Firenze, Overview allegato n.15 di Architettura e Paesaggio.

Bezzini L., Guagnini E., “Vini di Bolgheri e altri vini di Castagneto Carducci”. ed. Le Lettere, 1996

De Ricci L. et al., “Corsa Agraria della Maremma”, Giornale Agrario Toscano, 1832

Garoglio G., “La nuova Enologia”, eds. Istituto di Industrie Agrari Firenze, 1963

Scalzini E., “Inventario dell’archivio della fattoria Espinassi Moratti di Castagneto Carducci (1781-1981), ed. Comune di Castagneto Carducci

Villifranchi G.C. (alias Saverio Manetti), “Oenologia Toscana”, rivista il Magazzino Toscano, 1773