(continue from here)

According to Columella, those who want to start an agricultural business must not miss three things: knowledge, the will to do and money.

In fact, he says, the first two might be enough. However, he reminds us with subtle irony, that the possibility of spending is useful especially for those who lack skills, because in this way they can repair the mistakes they make.

Nothing could be truer!

[one_second][info_box title=”The relaxing villa in the vineyards of Pliny the Younger” image=”” animate=””]

Pliny the Younger proudly recounts the splendid view on its large vineyards, which he can enjoy from his villa in the Upper Tiber Valley in a letter to his friend Lucius Domitius Apollinaris, known as the letter “of the villa in Tuscia”.

Pliny was born in Como on 61 or 62 A.D. (death 113-114) and was nephew of the famous (and quoted by me several times) Pliny the Elder (uncle on the mother’s side). He was a lawyer and a high state official. It had large properties in different parts of Italy but the most loved seems to be the estate of the Tiber valley in Etruria (called Tuscia by the Romans). It is located in present-day Umbria region, between San Giustino and Città di Castello.

They aren’t the time of the 100 jugeri of Cato or the small (but wonderful) Palaemon’s vineyard. We are talking about a large latifundium, which Pliny has inherited and, in a small part, personally enlarged. He owned land for an estimated total of about 10,000 hectares, scattered between a villa on the sea near Rome, one on the hills of Tuscia and two on Lake Como, plus a stately home in Rome and one in Como. The Tuscia property included eight thousand jugeri, about 2,000 hectares (1 jugerum is more or less ¼ hectare), with various crops, which gave him an income of 400,000 sexterti per year.

Evidently, he is not a winegrower. Pliny himself says that he loves this estate more than the others essentially because he considers it the most comfortable and most relaxing, far enough away from Rome to allow him perfect tranquility. Here he could dedicate himself in peace to his otium which, for the Roman intellectual of the time, was the time he could spend studying and reflecting, when he was free from the tasks of political and public life.

Pliny still represents the landowner who well manages his properties, not that who dedicates them above all to grazing, abandoning them to the degradation. He writes, with his traditional patrician mentality, that the only legitimate gain for him is that which comes from the land. In fact, he did not use his assets for other forms of investment. In his writings, he admits (honestly or not) that he does not feel rich. He says that his income is fluctuating (as normally happens in agriculture) and it is just enough to allow him to sustain the decorum required by his position as senator. His earnings allow him just a frugal life, he write, with the opportunity to indulge himself only occasionally some extra expense. However, he was careful also in these. Above all, he was a philanthropist: apart from the purchase of some statues and the construction of temples in his properties, he donated a plot of land to his ex-nanny and made several donations to his hometown, Como. He built there a public library, created a food bank for the poor giving some lands and, in his will, he bequeathed a thermal building.

Returning to the letter and his estate in Tuscia, he describes the Apennine landscape with evident love. He tells of a large amphitheater with hills, and the mountains covered with woods. The cultivations extend both in the plains and on the hills, “rich in fertile land”.

“At their feet and on each side, there are vineyards that draw a single plot far and wide; from their limit, almost from their margin at the bottom, the vines married to the trees begin”. (Sub his per latus omne vineae porriguntur, unamque faciem longe lateque contexunt; quarum a fine imoque quasi margine arbusta nascuntur).

The first slopes of the hills are completely covered with vineyards, called vinea, the low vines. They completely surround Pliny’s villa and, as he says, almost seem to enter the rooms. In the flat area, there are instead the long rows of the arbusta, the vines married to the trees, alternating with fields and meadows. Unfortunately, as you could read in other translations of this famous letter, those unfamiliar with Roman viticulture translate the word arbustum (pl. arbusta) with groves or even hedges (sic!). The married vine has been and still is often lost in translation, as I had already told here.

Pliny’s description has been confirmed by the archaeological researches in the Tiber valley. The foothills areas had been chosen by the rich for their villas and were dominated by intensive vineyards, cultivated with slave labor. The plain was mainly managed by small farmers. They originally owned the plots, assigned them in the past with the centuriation. At Pliny’s time, they had become renters of the landowners.

It seems that Pliny, like many other owners, sold the grapes on the plant to entrepreneurs who took care of the harvest, production and sale of wine. The wine of High Tiber Valley was sold above all in Rome city. It seems that, as frequently happened at the time, Pliny (or more easily his administrator) negotiated the grapes of the manor property but also of the rented winegrowers (coloni). It may seem normal in the event that they paid in kind, a share of grapes or wine (this contract was called colonia partiaria). The administrator was concerned with selling the renters’ product portion also. The same happened even if the renter paid the rent in cash (rent contract called locatio-conductio). In this case, the landowner helped the settler to monetize his work, thus also ensuring himself also to be paid. The social relationship seems very equitable, far from the exploitation that the rented farmers will suffer in later periods or in other territories.

The difference between vinea and arbustum was not only social, shared between gentlemen and winegrowers. In another letter, Pliny stresses how important is the diversification in agriculture to be sure of having an income. It therefore emerges that the differentiation in vinea, arbusta and other crops was a thought-out strategy of the landowners, in order not to take too many economic risks.

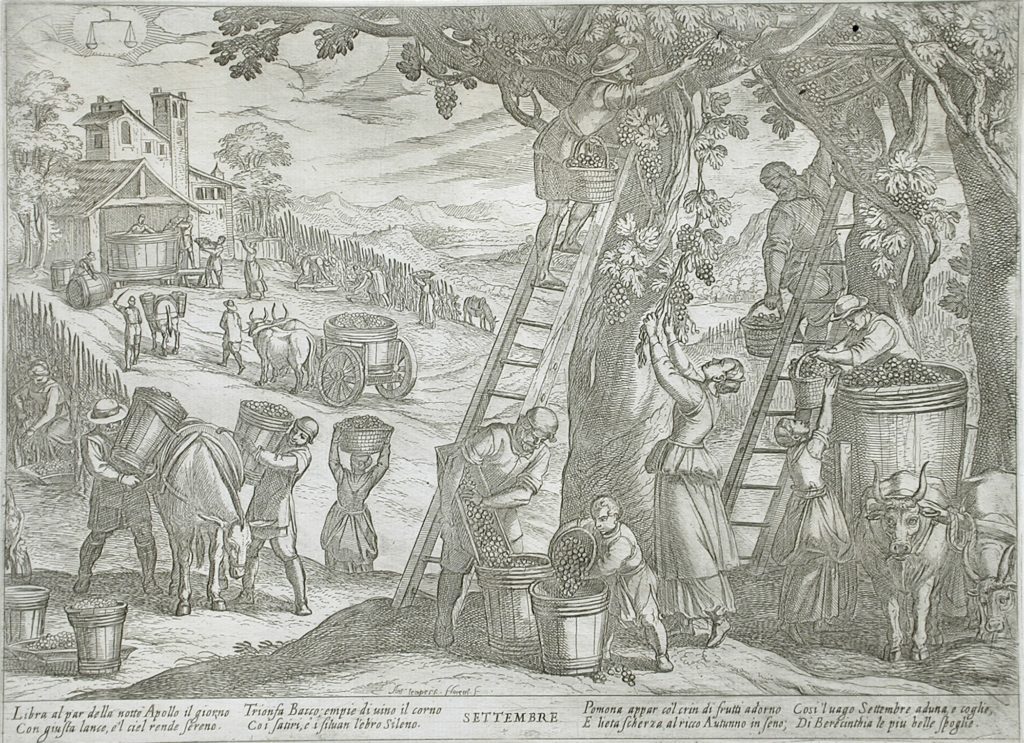

The relationship between vinea and arbusta in Italy will undergo fluctuating oscillations in the centuries to come, without neither system ever disappearing completely (if not in our day). The little viticulture of the Medieval era, restricted around the villages and also brought within the walls of cities and castles, will see the vinea prevail, more suitable for small spaces. In later periods, especially from the XV-XVI century, with the possibility of returning to the open fields, there was the clear prevalence of the arbusta, the married vine, with the large extensions of promiscuous cultivations (as in the image). Finally, contemporary viticulture (from the mid-twentieth century), increasingly specialized and also mechanized, has led to the absolute affirmation of vinea and the definitive disappearance of the ancient culture of the arbusta, the vine married to the tree.[/info_box][/one_second]

The knowledge, therefore, for Columella is essential and is the reason why he felt the need to write his treatise, De Re rustica (60 or 65 AD). It is certainly the best source to understand the work of the vintner of the time. It is not a literary work, but a real technical treatise. It is so precise, detailed, with rational observations, to be considered the first agronomic text in history. It remained as a reference in Europe until the end of the eighteenth century. However, Columella represents the acme of knowledge of his time, a moment (like many in history) in which knowledge was not universally diffused.

A general and more practical aspect, which struck me when reading from Roman viticulture, is that at the time they had an incredible number of agricultural tools, with many specific functions. For the cutting work in the vineyard, there was a billhook with points, used only for this purpose, called vineatica or vineatoria falx, the symbol of the winegrower. It remained until recently in central and southern Italy, with the name of “pennato“. Columella is recommended, for all cutting jobs, to always take great care not to injure the vine too much, to avoid diseases and pests, as we know today. The wounds, he advises, must be closed with tree resins or moist soil mixed with the oily deposit.

The vineyards

Columella lists the vine cultivation systems of his time. I have already mentioned some of them, but let’s see them summarized here, as the Latin author describes them.

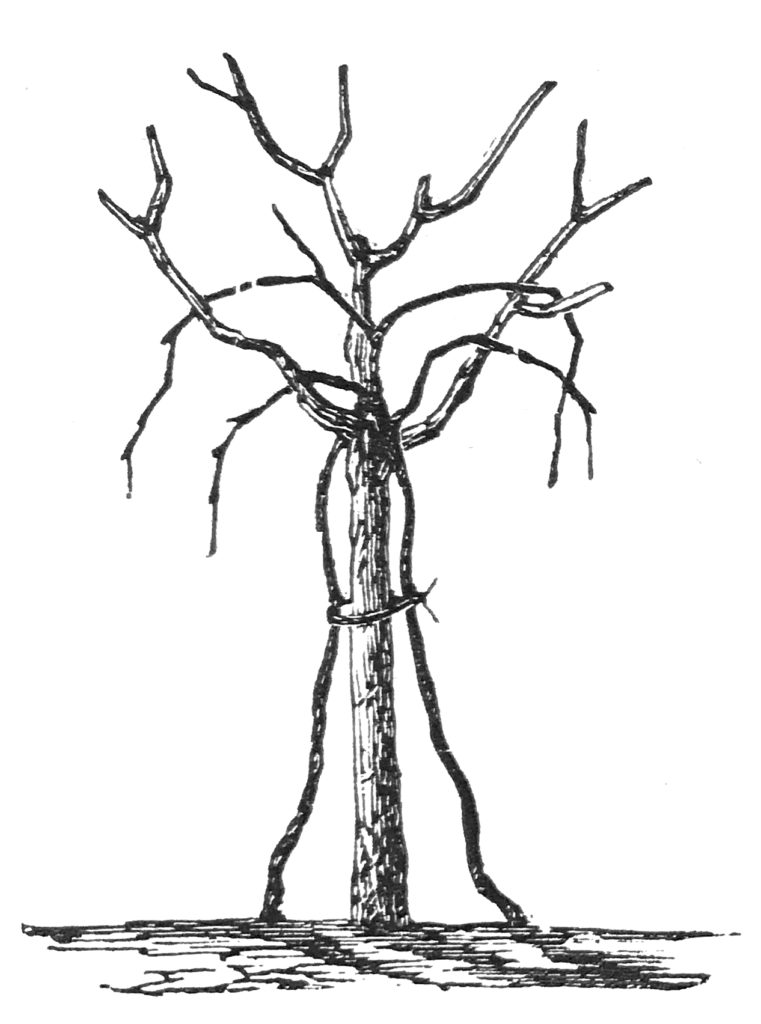

The married vine, i.e. the vine training system to a tree vine, in Latin arbustum, was the traditional Roman system and the most widespread, of which I have already widely spoken in many previous posts, describing its origin and peculiarities (here, here, and here). I quickly remember the descriptions given by Pliny and Columella (here you can try their origines). The arbustum is nomed Italian (arbustum italicum), because widespread in central Italy (at the time the only part of our peninsula that was called Italy): the vines (usually two) are climbing on a single tree. Columella explains that elm is the favorite because it grows well in many types of soil and its leaves are very suitable for foraging oxen. Poplar is not very useful for animals feeding but is used in some territories (such as Campania). According to Columella, the ash is better, used in steep and mountain soils that are not suitable for elm. Above all, its leaves are excellent for goats and sheep. Cato also mentiones the fig tree. In Etruria, the original homeland of the arbustum, we know that maple was mainly used and it continued in Roman period.

The second system is the Gallic system, called arbustum gallicum or rumpotinum, present mainly in Northern Italy, in which the vine branches (called traduces) passed from tree to tree. Not very leafy trees are used, including well-trimmed elm, maple, cornel, hornbeam and manna ash tree. Willow is used only in very humid soils. The shoots, if they cannot reach each other between tree and tree, are joined by a rod (horizontal poles). They can also be supported in the middle by vertical poles.

These two systems remained in Italy until the mid-twentieth century.

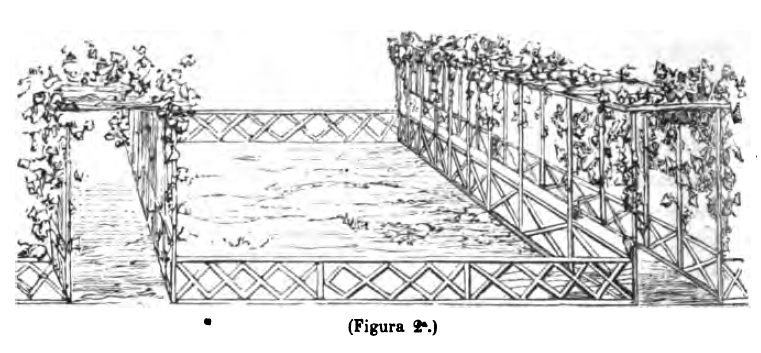

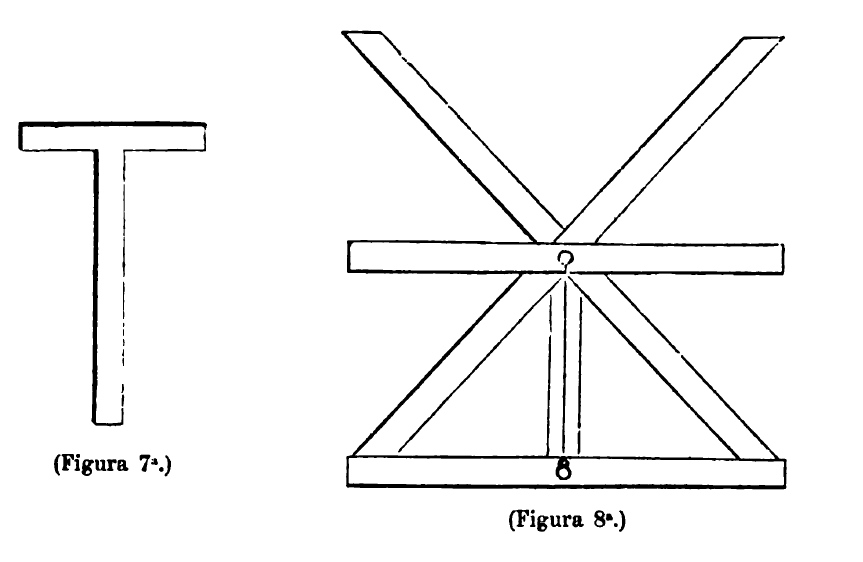

Columella calls “yoked vines” all the types of cultivation in which the vine was supported, from the single pole to the more complex structures, made of poles, canes, ropes and pruned branches. The espalier system was called jugatio directa: all modern ones derive from it. Varro says it gives an excellent wine because the vines do not shade each other. There were also particular local systems, for exemple the Arpinate characata vine, where each branch was supported by one cane, in a circle system. The pergolas were called jugatio compluviata (from the name of the compluvi of the houses, in the drawing below).

Columella says that, among the many forms of viticulture in the provinces (i.e. Sicily and other southern regions), he greatly appreciates the bush traning system, without support, which he calls “surrette” vines, (in Italian today is alberello). It also describes the creeping vine, that he calls “strata“: it is a sapling with branches twisting on the ground. Columella says that it is used in extreme climates. The branches are superimposed on each other to prevent the grapes from touching the ground and rotting.

Since it was common to cultivate wheat or other crops among the vines rows, in general there was a tendency to leave spaces of two to twelve meters, to easily pass with the plow pulled by oxen. In the vineyards of the most inaccessible areas (mountains, etc.), the rows were tighter, up to a meter and a half, and jobs were done handly, with the hoe. Columella and Pliny both argue that the best plant system in the vineyards is the quincunx one, like the number 5 on a dice, useful for the sun exposure but also “because it offers a beautiful appearance” (Pliny).

The animals were considered one of the greatest dangers of the vineyards, especially the wild ones or the flocks that had escaped control. The low vineyards were always fenced, especially with hedges. Those trained to trees could be left open, with the possibility of using them for grazing, unless there were other crops to protect in the middle. The oxen which pulled the plow or the cart had muzzles, otherwise they would have eaten the shoots and the tender leaves of the vine.

Vine propagation and implantation

A very long and detailed part of Columella’s treatise is devoted to the propagation of the vine, that is, the careful selection, creation and management of the cutting. The cutting was called malleolus (remained in Italian of more recent times as “magliuolo“), the little vine born from seed is the viviradicem. The Romans didn’t used grafted vines, as we have to do today because of phylloxera (it will arrive in Europe only in the Nineenteenth century).

The trenching of the vineyards was done in different ways. The pastinatio, testified by the written sources, consisted of hoeing the whole surface, at about 60-90 cm of depth. Other systems instead provided only for the excavation of long strips of soil, where the vines were implanted. Depending on the type of soil, they could do dimples, called sulci, or deeper trenches, called scrobes. In some archaeological sites, in shallow volcanic soils, traces of these excavations have been found still today, because, the ancient workers had to affect the underlying tuff layer. These systems have remained in Italy until recent times, until the spread of mechanical means.

Different types of canals were also made in the vineyard, some for draining water from the more stagnant soils, others for irrigation in the drier soils.

At the bottom of the planting hole, they placed stones, marc mixed with manure, both as fertilizer and to “warm up” the cuttings. Then, they filled the holes with earth. If the soil was very poor, it was recommended to add fertile earth to the pit.

The cuttings were planted on both sides of the pits, so that they came out on opposite sides. To plant the young vines, they used the pastinum, a long stick that ended with two prongs. In more recent centuries it will be called auger (trivella) in Lazio and gruccia in Tuscany. We still use it today.

The young vines were tied to a cane so that they could grow straight, to then lead them to the form of training, as we do today. Especially in the first year, the Latin authors recommend to take care of the young vineyard, irrigating if needed.

Pruning

Pliny tells that the vine pruning started at the time of King Numa. It seems that at the beginning the vintners refused to climb the trees (the vine training system to a tree, the original Roman form), which often were very tall, for fear of falling (“pericula arbusti“). Then, the practice of guaranteeing workers of the vines also the coverage of funeral expenses was introduced.

Several centuries after Numa, Columella writes, in a very modern way, that pruning must be done with three purposes: thinking about the production of the fruit, choosing the best shoots, studying to make the vine long-lived. For optimal pruning, he writes, the winegrower must remember the production of the previous year of each plant. He distinguishes and explains the long and short pruning, for each different vine training system. The creeping vine, instead, has only a very short pruning. He calls the spur (the part that remains of the branch after the short pruning) custodem, but he says that it is also called resecem or praesidiarium.

Columella says that pruning can be done in October, after the leaves have fallen, when the shoots are ready. If the winter is too cold, however, it is better to wait after mid-February. It is correct, because some varieties bear the winter frosts badly, if they have already been pruned. However, he writes that the early pruning gives more wood, the later one more grapes. Today we know that the time of pruning affects above all the spring budding time of the vine. The too early pruning makes the vine sprout early, exposing it more to the risk of the late frost. (… continued…)

Bibliography:

“De re rustica”, Lucio Giunio Moderato Columella (60-65 d.C.), tradotto da Giangirolamo Pagani, 1846 (preferisco le traduzioni dell’Ottocento perchè, avendo una viticoltura e tecniche di produzione del vino più simili a quelle antiche delle nostre, sanno spiegare meglio i concetti e trovare le parole giuste).

“Interventi di bonifica agraria nell’Italia romana”, a cura d Lorenzo Quilici e Stefania Quilici Gigli, ed. L’Erma di Bretchneider, 1995.

“Storia dell’agricoltura italiana: l’età antica. Italia Romana” a cura di Gaetano Forni e Arnaldo Marcone, Edizioni Polistampa, 2002

“Le proprietà di Plinio il Giovane”, V. A. Siragola, 1957

“Territorio e paesaggio dell’Alta Valle del Tevere in età Romana”, Paolo Braconi, 2008, in F. Coarelli – H. Patterson (eds.) Mercator placidissimus. The Tiber Valley in Antiquity. New research in the upper and middle river valley, Atti del Convegno, Roma, British School at Rome, 27-28 febbraio 2004, Roma 2008, pp. 87-104

“La villa di Plinio il Giovane a San Giustino”, Paolo Braconi, 2008, in F. Coarelli – H. Patterson (eds.) Mercator placidissimus. The Tiber Valley in Antiquity. New research in the upper and middle river valley, Atti del Convegno, Roma, British School at Rome, 27-28 febbraio 2004, Roma 2008, pp. 105-121

“La villa di Plinio il Giovane in Etruria, Giovanni Caselli,

“La viticoltura e l’enologia presso i Romani”, Luigi Manzi, 1883, .

“Storia della vite e del vino in Italia”, Dalmasso e Marescalchi, 1931-1933-1937, .

“Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano”, Emilio Sereni, 1961, .

“In vineis arbustisque. Il concetto di vigneto in età romana”, Paolo Braconi, Archeologia delle vite e del vino in Etruria” A. Ciacci – P. Rendini – F. Zifferero (eds.), Archeologia della vite e del vino in Etruria (Atti Scansano 9-10 settembre 2005), Siena 2012, pagg. 291-306.

“Catone e la viticoltura intensiva”, Paolo Braconi.

“Quando le cattedrali erano bianche”, Quaderni monotematici della rivista mantovagricoltura, il Grappello Ruberti nella storia della viticoltura mantovana, Attilio Scienza.

“Terra e produzione agraria in Italia nell’Evo Antico”, M. R. Caroselli.