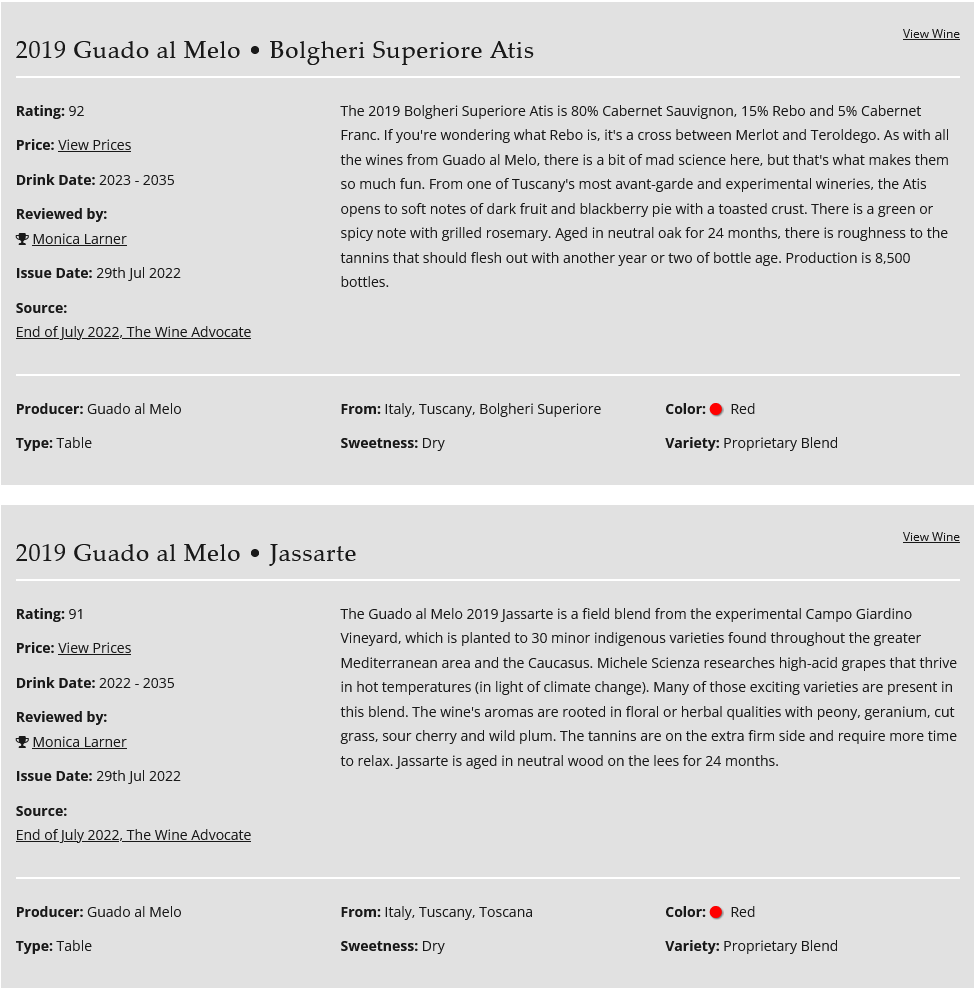

Wine Advocate: good but a little crazy

Many thanks to Monica Lerner for her appreciation of our wines, especially Atis and Jassarte. It is corious that this good American journalist always writes interesting comments for us, between the astonishment and that sympathy that is attributed to people what you consider a bit crazy 😊.

Last year she wrote that we are a very creative winery. This year she writes: "there is a bit of mad science here, but that’s what makes them so much fun".

May be she thinks we are a bit crazy to make counter-current choices in the world of wine which often prizes the homologation?

So, crazy or brave that we are, we consired her comments as a enormous compliment. We hope to have her as our guest as soon as possible, to have even more fun! (and to tell her about the experimental research and the rediscovery of the ancient Italian traditions behind these choices of ours)

Anyway, thank you very much, Mrs. Lerner, we really appreciate that you have tasted and reviewed our wines.

We're certifing our wines as sustainable

Be the change you want to see in the world.

(Gandhi)

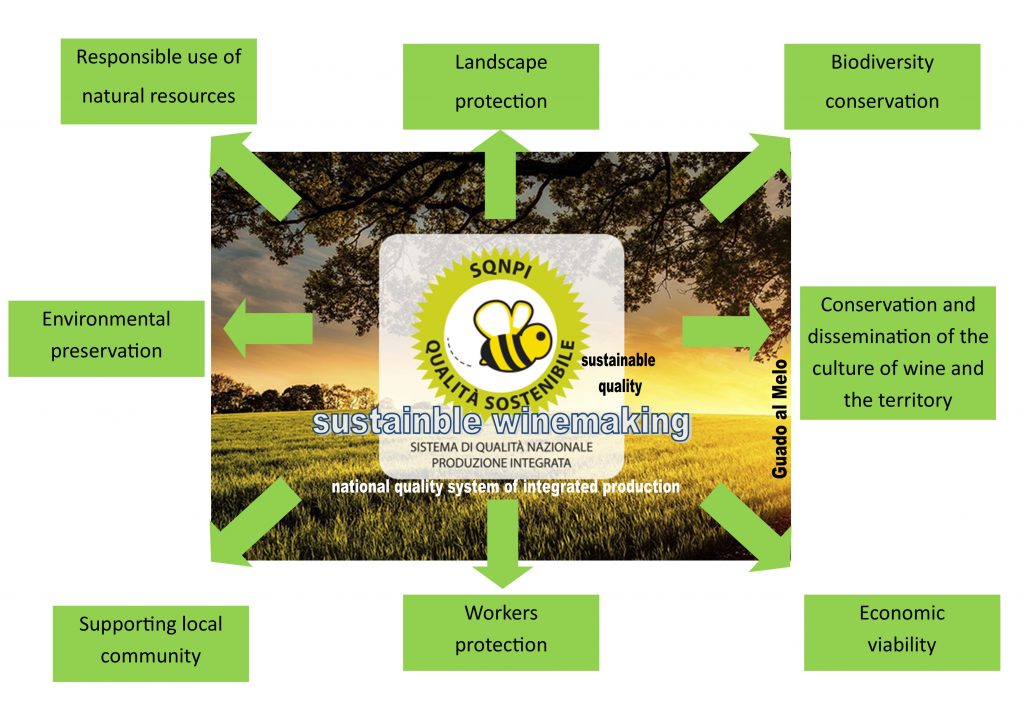

I am glad to inform you that with the 2022 harvest our wines will be certified for the production of sustainable wine, according to the single sustainability standard set this year by the Italian Ministry, with the SQPNI mark (National Quality System of Integrated Production). The logo is the nice bee you see above, very evocative of a winegrowing that respects the environment and health. However, do not stop at this somewhat naïve appearance: there is a very rigorous and solid technical-scientific system at the base, that of integrated viticulture

We don't become sustainable now because we certify ourselves. Conversely, we certify something we have always been doing. Those who know us know that, since the birth of Guado al Melo, we have been working to make it a completely sustainable artisan company (on the management of the vineyard, the bio-architecture cellar, the management of winemaking, the recycling of rainwater, the spreading of the culture of wine and the territory, …). We are sustainable in essence, in our way of life and in the constancy of evolving over time.

Our certification starts with the 2022 harvest. You will therefore have to wait a while to see the pretty bee on our labels. The first wine will be the Airone 2022, which will be released more or less in March 2023. Then it will be all the others.

Is it necessary to be certified? I think that the certification systems can have limits, which is why we have not certified ourselves with systems we did not believe in. If the system is done well, however, it is an extra guarantee towards our customers.

Why only now? We waited for Italian politics to define a single sustainability certification system, based on a rigorous technical-scientific system. He did it late and, as always, in a tortuous and somewhat confused way. However, we are confident that we are at the beginning of a path that will be increasingly fruitful.

It is not our first experience. The Tuscany region has been verifying our adhesion to voluntary integrated viticulture for twenty years. A few years ago we had already participated, as a pilot-winery, in the birth of the first Italian sustainability certification, called Magis. The project, born in 2009, supported by several universities and research centers, was very rigorous. He was recognized among the best in the world by the OIV. Unfortunately, it ended after a few years, because it was too ahead of its time: many wineries pulled out because they did not see a vantage of image.

Sustainability was born from the evolution of integrated agriculture (integrated pest control) in the 90s. A few years later, some national certification systems were born in the wine-growing countries of the New World (first in California, then New Zealand, Chile, South Africa, …).

Italy (and Europe) lagged behind in terms of certifications of sustainability. Until now, there were only the regional regulations of the integrated viticulture, which is very excellent in Tuscany (my region, I have few knowledge of the other Italian regions). Sustainability spread in the society in recent years. Some certifications have thus been created recently, which have benefited from the rigorous system already set up by Magis. This year the Italian Agriculture Ministry has started working to define a single sustainble standard, based on the SPQNI system.

Unfortunately, this delay is due to the fact that in Italy (and Europe) the public debate on agriculture/environment issues has not always been dominated by the rationality, but often by clichés and romantic "natural" practices, perfect for politics or the most superficial media or corporate marketing, but little or not at all effective in the winegrowing.

If we really want to do good for the environment and for ourselves, the essential thing is not to stop at attractive slogans but to work to find truly effective methods that allow us to achieve concrete goals. In fact, despite all this, the world viticulture research has worked a lot in recent decades and many winemakers have kept up with the it.

How the sustainable certification works

The pillars of sustainability are three, closely intertwined with each other: the environmental, economic and social.

The protection of the environment and health in the vineyard passes first of all from the technical-agronomic practices, which are based on voluntary integrated viticulture (which we have always done and which I have therefore told on our website and in some posts here). It includes multi-disciplinary viticultural practices that allow for high quality grapes with the lowest (measured) impact on the environment. Other check points are added to it. Some are related to the work in the cellar: the traceability of each wine from the field to the finished bottle, the containment of the winemaking products (we do not use any), the verification of the absence of residues in the finished wine. Moreover, there is a control of other winery's general parameters, in relation to energy consumption, water saving, and the fate of waste.

If you don't know what voluntary integrated viticulture is, I have written a reminder in the green box. If you know it, skip it.

What is the integrated viticulture? It is the most rational way to solve the environmental impact problems of viticulture. It is not a "philosophy" but simply the choice of the best practices available, taken from tradition and the best innovations, with the aim of minimizing human interventions and the use of each phytosanitary product in the vineyard (possibly up to elimination), maintaining at the same time an adequate quality and quantity of the grape (and wine). Therefore, a practice is accepted only if, at the same time, it satisfies two conditions: it works well and with the minimal impact on the environment. It is a system that benefits from decades of study and experimentation. The concept of "integrated pest management" was born in the 70s and has grown considerably over time, with an important leap especially in the 90s.P

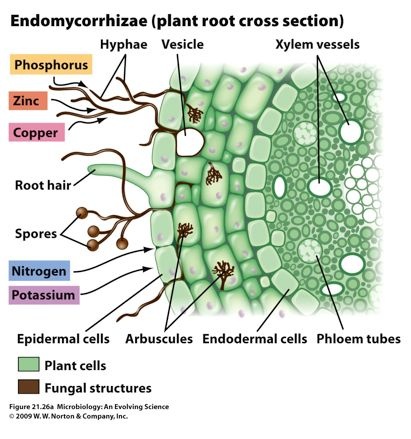

Why is it called integrated? Because it considers the vineyard as an integrated ecosystem in which numerous living organisms interact, influenced by the situation of the soil, climate and atmospheric variations. The multidisciplinary approach only, which manages to bring together all the knowledge on these elements, allows for the minimum possible impact in agriculture.

Some key concepts: Among the practices used there is a priority scale. Those that allow the prevention of adversity are always favored first. Where this is not possible, biological control systems are used. If even this is not possible, there is the use of plant protection products, chosen from those that have demonstrated excellent effectiveness and the lowest impact on the environment. They are used the smallest amount possible, only where it is needed. In this way, we can achieve a very low impact, which research is trying to lower more and more. To make decisions, it is essential to collect the data that allow us to understand what is happening in the vineyards (from observation to the collection of atmospheric data, …) so as we promptly intervene with the best methods for that particular situation, only where it is needed. A fundamental principle is the integrated approach: each problem is faced from several fronts, in order to minimize the impact of each intervention. Another basic principle is the damage threshold, that is, there is no need to "sterilize" the vineyard, but it is sufficient that the adversities are below a minimum threshold that does not affect the quality of the grapes.

Why is it little talked about ? Honestly, it has always been my question! Even if it is not famous, it is applied by many companies of Italian (and worldwide) winemakers. Above all, I always wonder why wineries, universities, regions and the technicians who deal with it hardly ever talk about it. Or are they not listened to?!?! I have given myself several explanations. It is a complex system, not very suited to the simplicity required by the media and marketing, which want concepts that are not well reasoned, easy and charming. In my experience, I also realized that this system is generally chosen by old-fashioned winemakers' companies, which do not put marketing first but the optimal care of the vineyard, which on average are bad communicators (sorry, but unfortunately this is the case ).

However, it is not enough. Parameters relating to the economic and social sphere are also verified to complete the concept of sustainability. There are a series of checks on the integrity of the winery in relations with its workers, as regards safety and enhancement, as well as in relations with the territory and the rest of the production chain.

What is sustainable viticulture? It is the upgrade of the integrated viticulture. In the 90s, the scholars began to reflect on the fact that it was not enough to consider the impact in the environmental field. A complet sustainability must be integrated with the economic and social aspects.

Economic sustainability. For example, let's assume that I find a cultivation practice that does not have a negative impact on the environment but makes me produce very little product or it is of poor quality, or it costs me a lot to produce it … So, that practice is not sustainable, because it solves one problem but creates many others. Agriculture must give income to the people, otherwise it risks disappearing or it must depend on public funds to survive. It must also offer sufficient food products to meet the needs of the community, both in quantity and quality. In reality, this basic concept has always been inherent in the integrated viticulture, which has always sought practices with the lowest environmental impact but which, at the same time, maintain an adequate qualitative and quantitative level of the grape.

Social sustainability. Furthermore, every human activity must include respect for the workers and people who live in the area, fairness towards suppliers and customers (and the whole chain that is before and after), supporting the local community, maintenance and the spread of the culture of the wine and the territory, …

All these elements must coexist in the sustainable viticulture, or better, we must found the best possible mediation between them.

It is a supply chain and product certification. It means, unlike others, that we must demonstrate every year not only to follow some practices, but that there are the goals of the absence of residues in the vineyard and in the wine. So, we can "conquer" the bee on our bottles.

Bolgheri: hills, plains and soils, understanding a territory beyond the commonplaces

I love you, fruitful and pious land, and I admire you,

and I touch you, and I fill my hands with you,

and over you I bow my face, greedy, and

your healthy perfumes, grateful, I aspire;and in you the eye turning, in a short tour

I discover mountains and forests and valleys and plains,

…

(Edmondo de Amicis, Alla Terra)

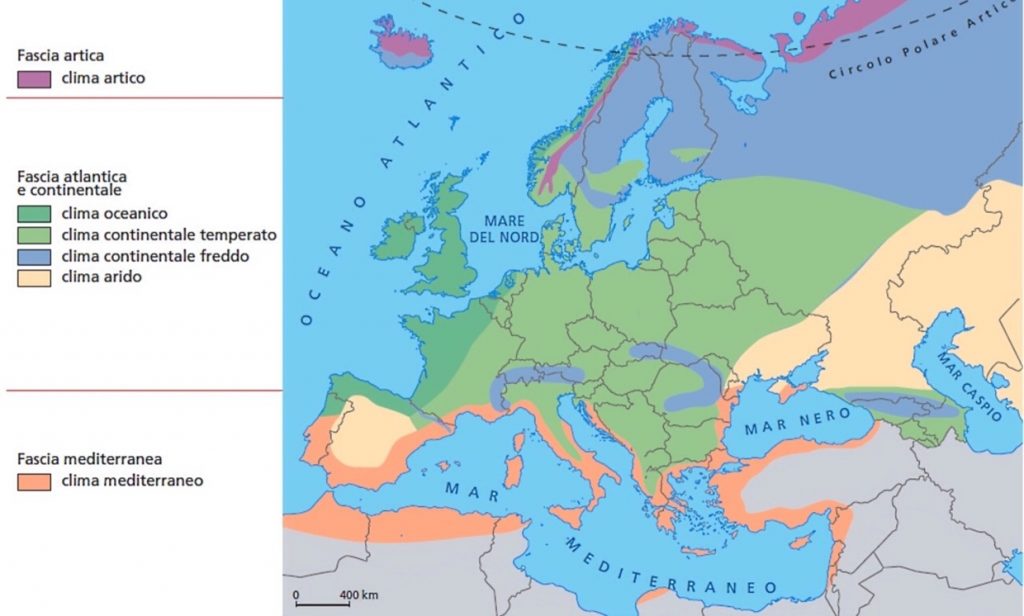

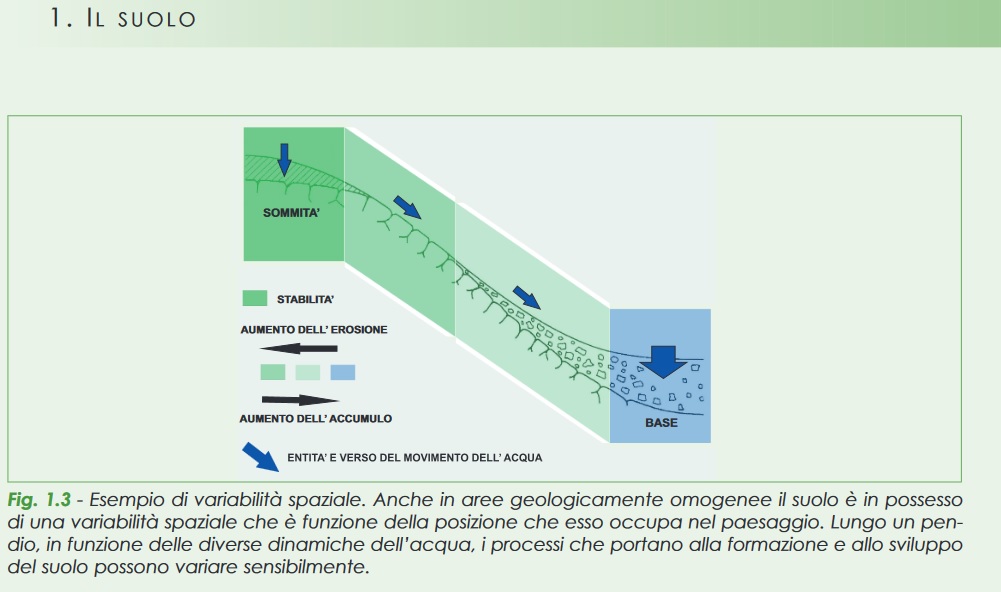

Often our visitors ask us why viticulture in Bolgheri did not develop in the hills. In fact, it mainly includes the foothills and lowlands. This question is understandable: how many times have you heard that the best viticulture is that on the hills? "Bacchus amat colles", Bacchus loves the hills, also wrote Virgil in the Georgics. Why is it not like this in Bolgheri (and elsewhere)? Because here there is so much sun :-) Let's try to understand better why.

Before answering this question, I invite you to reflect on the fact that, as in many other fields, also in wine there are some rules that may seem general but that, with a less superficial approach, you can understand that they are not exactly valid in all cases. The simplifications (or clichés) aren't rappresentative of the multiform diversity of the wine production. As I have often reminded you, viticulture is always local. The viticultural choices can change a lot between the territories, even between the vineyards. It is the particular conditions of soil, climate, micro-climate and variety that determine the best choices on where and how to create a vineyard, as well as on how to manage it. We must consider them if we want to make a great wine, a local wine with its splendid uniqueness.

Sometimes people tend to generalize using as a reference the choices of successful territories or famous producers or the reality they know best. However, if you approach a territory with prejudices, it becomes truly impossible to understand its peculiarities. The generalization is even more risky for the wine producers: reproducing ottimal patterns from other territories or companies in the vineyards can lead to errors which are then paid. In a suitable territory for the winegrowing, the lack of understanding of the vineyards is the great discriminating factor between the production of a great wine or not. The viticultural zoning studies are used precisely for this, to help producers make the best choices for their micro-realities (not to make quality rankings as is often thought). Bolgheri was one of the first Italian wine territories to do the viticultural zoning studies, carried out in the early 90s and continued until 2004, conducted by the University of Milan under the guidance of prof. Attilio Science.

So, let's go back to the original question. The concept of the higher quality of hillside viticulture was born correctly in territories with continental or similar climates. They are places where water is generally not lacking, indeed they are on average (or very) rainy. In these cases, the valley floor or the plains are places where there is an abundance of water, they are often also humid or even the water can stagnate in the soil. The vine is a very rustic plant but humidity is the worste condition for it. Too much water availability in general leads to an excess of vigor, which is a limit for the wine quality. The humid climates also cause several serious diseases, such as the downy mildew and the molds that affect the bunch. When the humidity becomes decidedly too high in the soil, major problems can occur to the roots and therefore to the plant itself, the rot and the root asphyxiation.

For all these reasons, the sides of the hills are often the most suitable for the vine in the territories characterized by these situations, because these places are the least humid and not too fertile. The problem of soil moisture is avoided: the water flows downwards, so the hilly soils are the most drained and dry. There are also better exposure to the sun, better temperatures and there is no stagnation of humid air. In the past, in reality, the optimal choice of the hill was often guided by other priorities. The most fertile and water-rich soils were reserved for crops essential for food, cereals or other. Given the rusticity of the vine, the leaner and poorer soils were left to it, often those of the hills, where it was difficult to cultivate anything else.

If these considerations are valid for territories such as those just described, it does not mean that they apply everywhere! There may be lowland areas without humidity problems to which these concepts do not apply. I would also like to add that the current climate change may lead to the modification of many consolidated models.

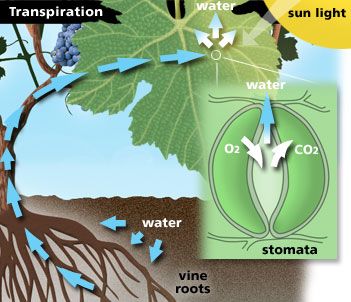

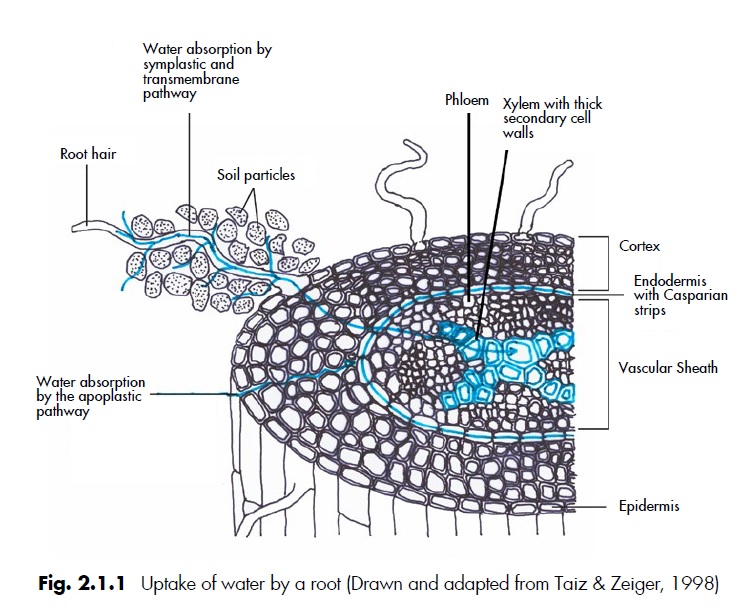

In the Mediterranean territories, such as Bolgheri, the climatic situation is completely different. The vine here is indigenous, this is its natural environment and does not even have many phytosanitary problems. What may be missing, unlike the continental areas, is precisely water. As I have mentioned several times, the vine does not need a lot of it, but it must also not be lacking in the important moments of the plant's cycle, otherwise it can undergo water stress that leads to the production of a few unbalanced grapes. The millennial viticultural experience teaches that the vine must undergo a slight stress to give the best grapes for making wine. Typically, less qualitative situations arise from two extremes: when the vine is too well or when the stress gets too high.

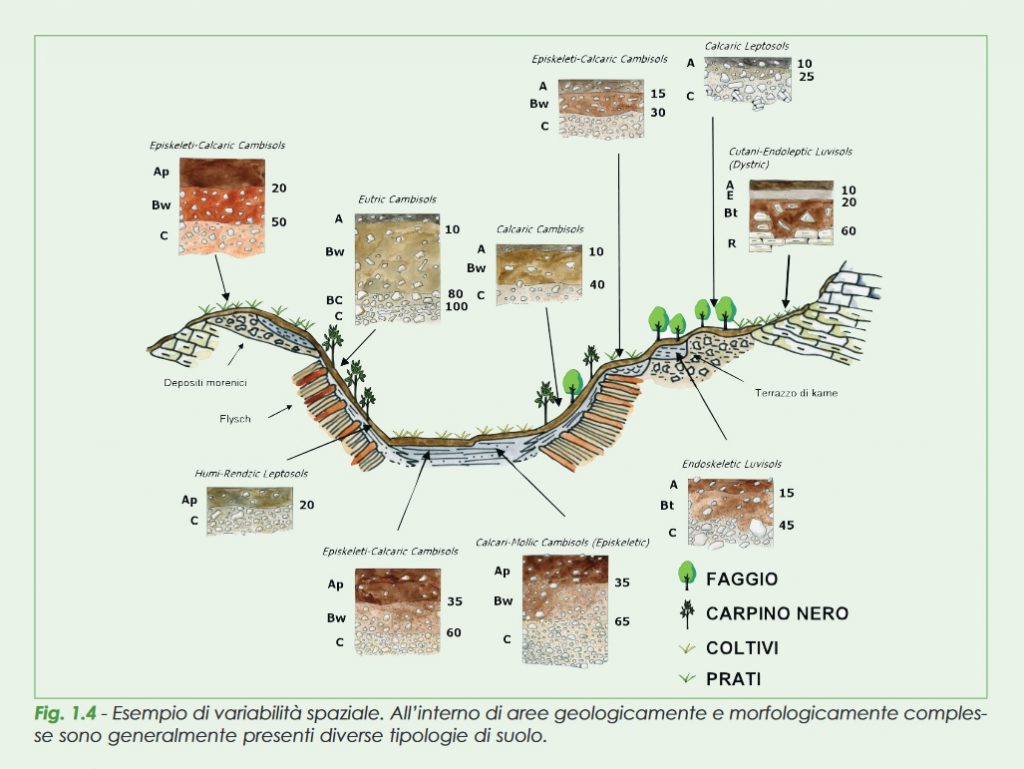

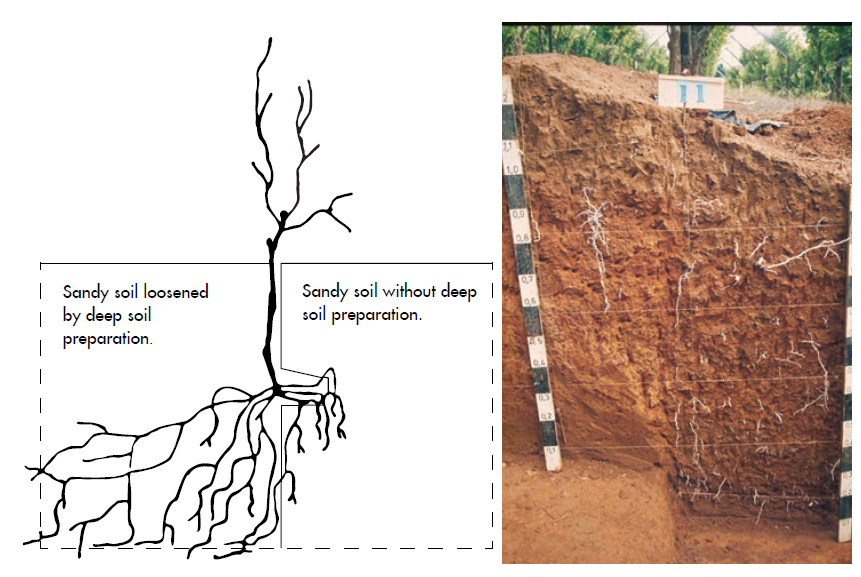

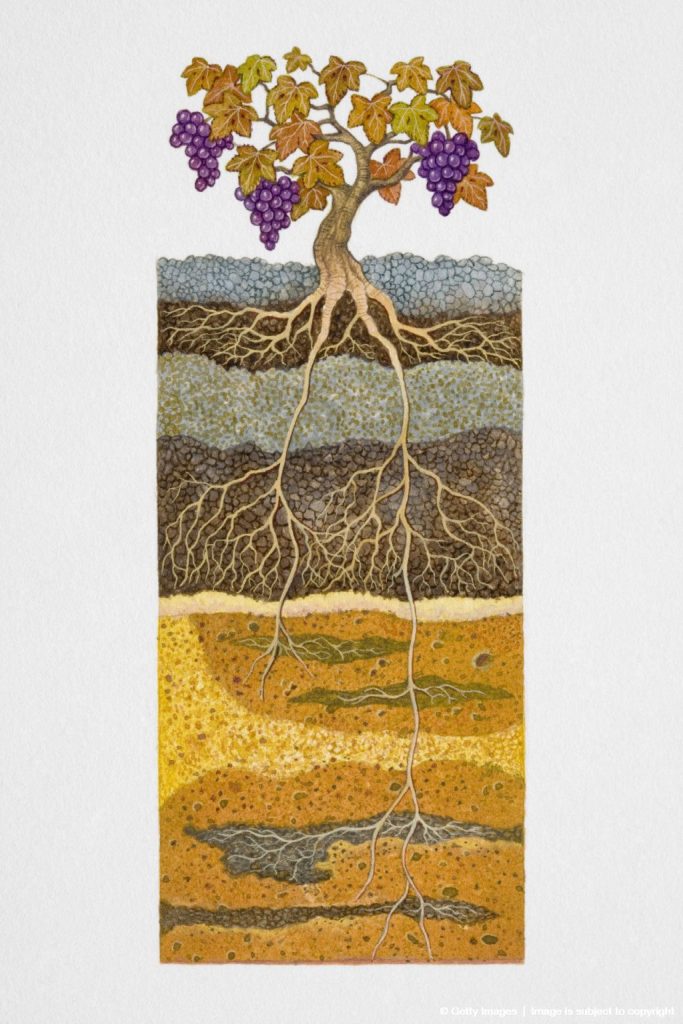

In these climates, the thin hill soils can be too poor and limiting for the vine, especially as regards the water availability. The soils are generally deeper in the foothills or lowland areas, so the roots can develop fully and can find water even in summer, where it has accumulated in the deeper aquifers during the cooler seasons. There is not even too much fertility; on the contrary, there is often the opposite problem: the mineralization of the organic substance in the Mediterranean climate is very speeded up by the high average temperatures. Of course, this is not necessarily the case everywhere: there may be difficult areas in the plains or favorable in the hills. For example, there are areas of the Bolgheri plain where the soils are made thin by superficial tuffaceous crusts. Some soils are poorly drained and flood in the cool seasons. Before deciding where to make a vineyard, a macroscopic examination of the area and then of the micro-situation is essential, with the support of zoning studies and a good geologist.

You will therefore have understood that, in a dry and breezy Mediterranean climate like ours, the continental concept of "low and high" is quite useless for these aspects: down there are no problems of humidity and the solar radiation is abundant everywhere. So, you understand why the right question to ask in many Mediterranean territories is not the altitude of the vineyards but rather the response of the soil to the long dry summer season.

The position of the vineyard in our territory is also important as regards the winds. Certain cold winds (Tramontana from the north and Grecale from the north-east) can be the cause of spring frosts, since the temperature here hardly goes below zero. Therefore, the areas that are too exposed to the winds are more at risk, such as the upper parts of the hills (of the slopes concerned) or the more open areas of the plains. On the other hand, the vineyards of the foothills, protected by the hills, or the areas sheltered by other natural or artificial obstacles (such as woods, rows of trees, etc.) are less exposed.

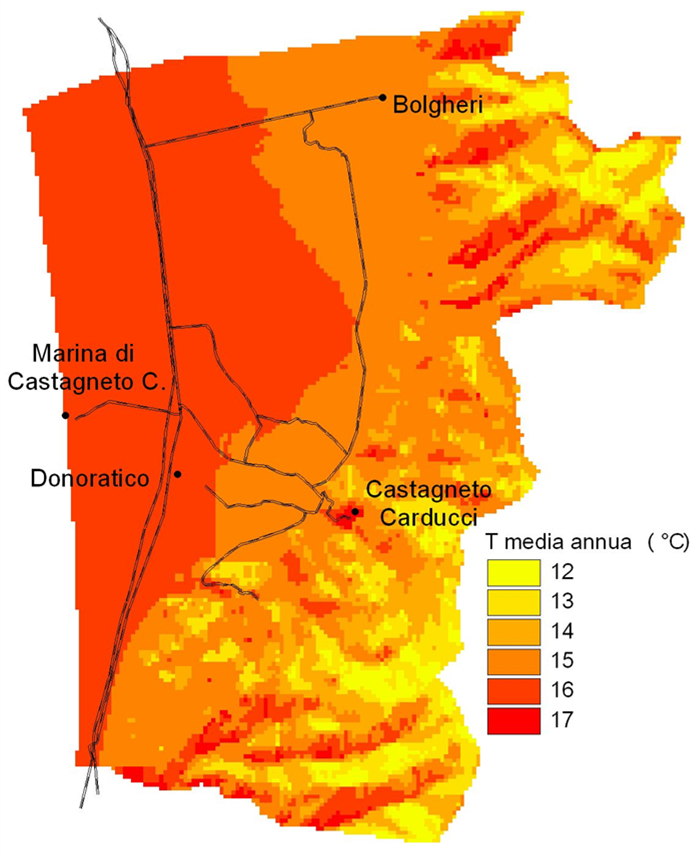

The main difference between hills and plains in Bolgheri DOC is linked to the differences in temperatures and as regards the summer temperature range between day and night. In general, Bolgheri enjoys a cooler climate on average than the neighboring territories. Inside it, the average annual temperatures are lower in the hilly area and increase going towards the sea. The temperature range is greatest in the small valleys between the hills, lower on the top of the hills and moving towards the sea. It therefore becomes important to understand which types of wines and varieties are best in each condition, without forgetting to correlate these data with the other elements described above, especially with the summer water availability.

In viticulture, the climate is inevitably related to the soil. It often happens to attribute a greater qualitative value to some soils. In reality this is not always true. There are examples in Italy and around the world of great wines on all types of soils, from predominantly clayey to sandy or silty ones. The texture of the soil (i.e. the size of the soil particles, in the relationships between its various components, from the finest to the coarsest) is important as it affects the expression of the wine characteristics and the work choices of the winemaker. However, it does not necessarily define different qualitative levels, only different sensory characteristics. It is also true that there may be varieties that prefer one or the other type of soil but many others simply give different results. For example, in a very general way, the soils with a higher clay component produce powerfull wines, the sandy soils produce elegant wines. Which are the better? It depends only on personal taste or, at most, on the taste trends of the moment.

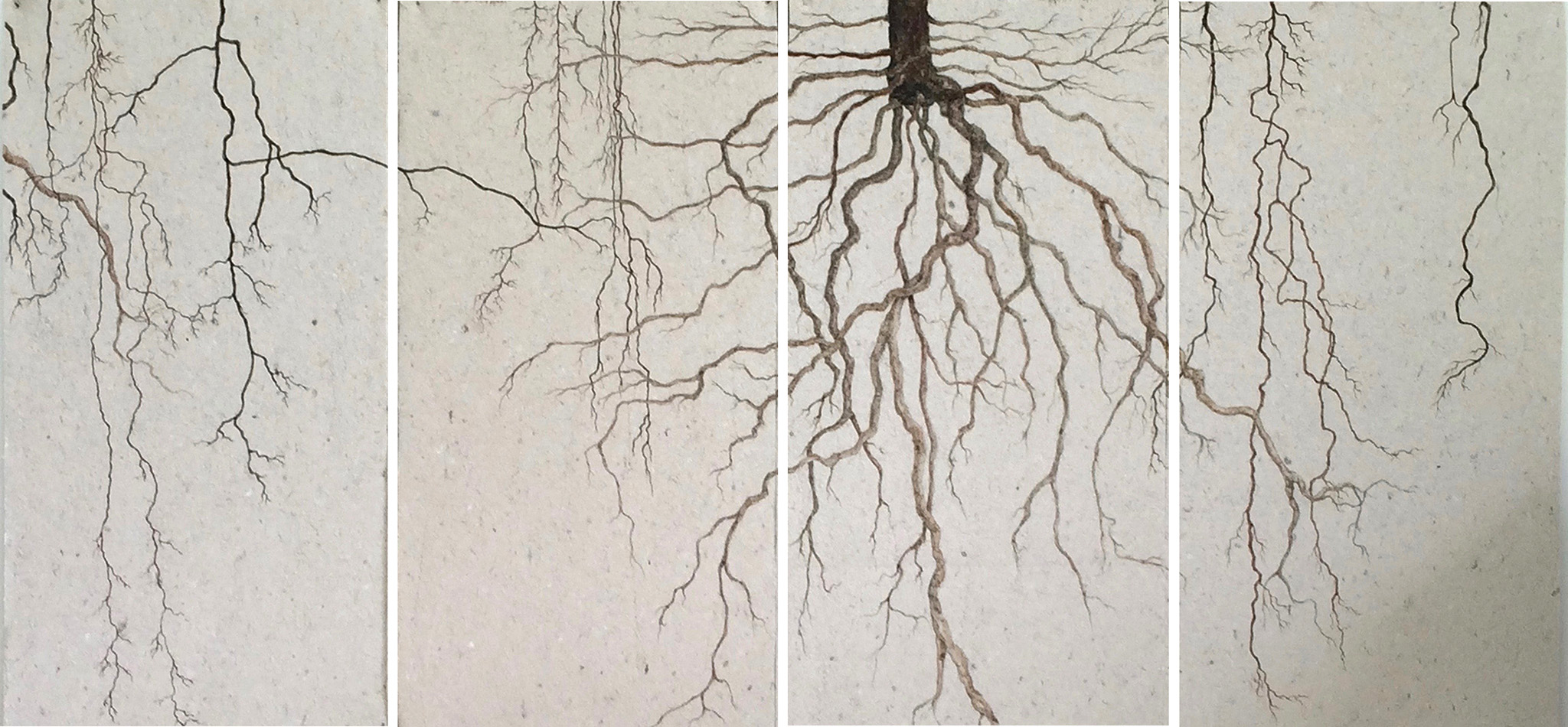

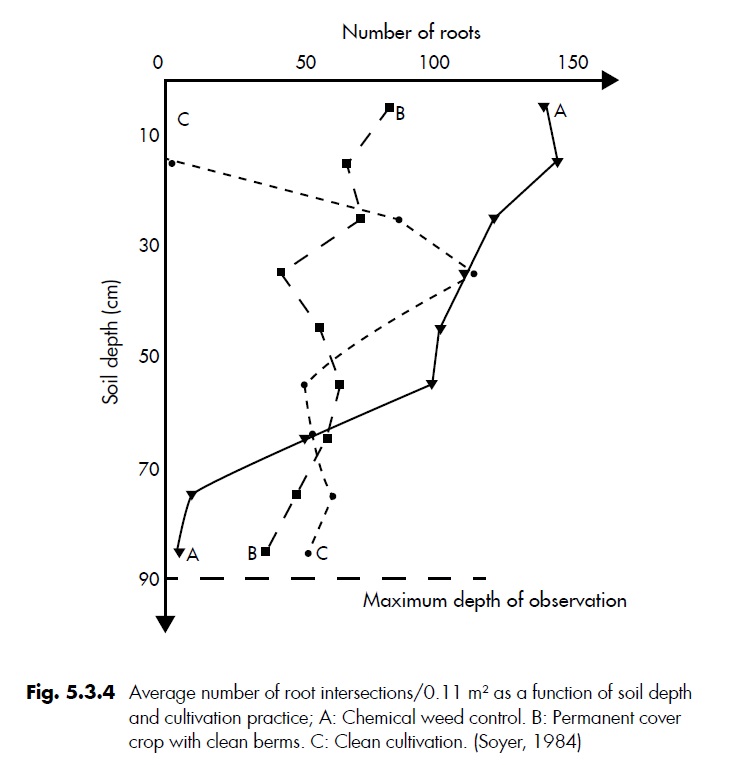

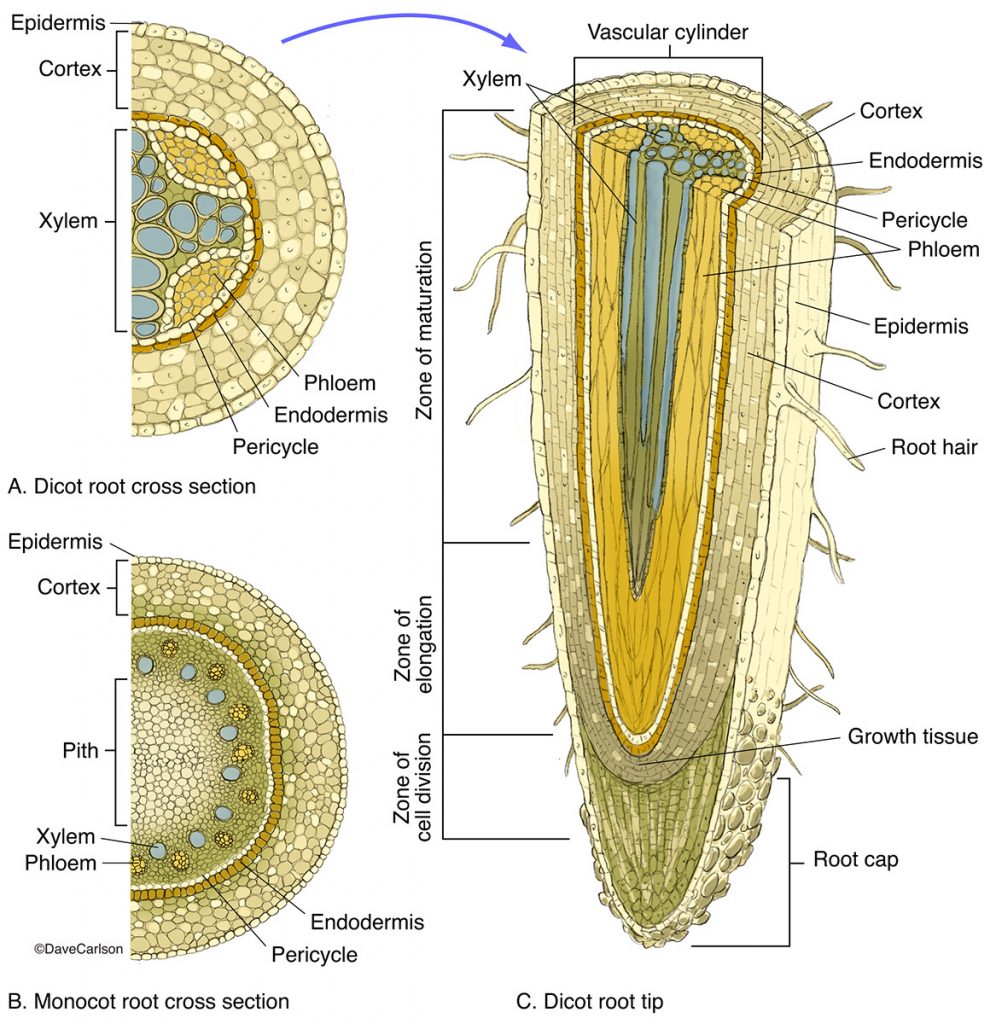

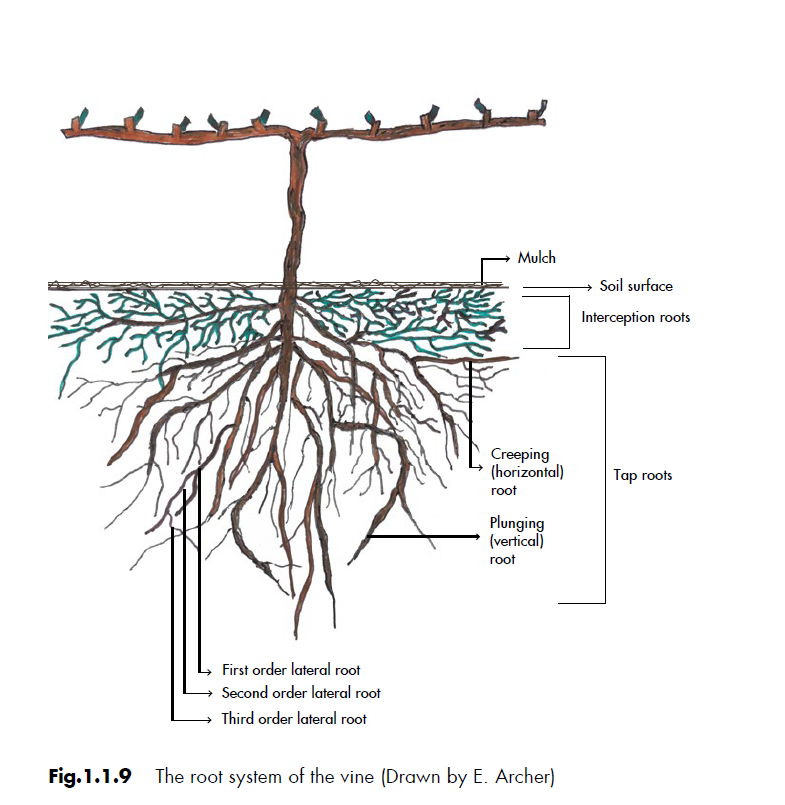

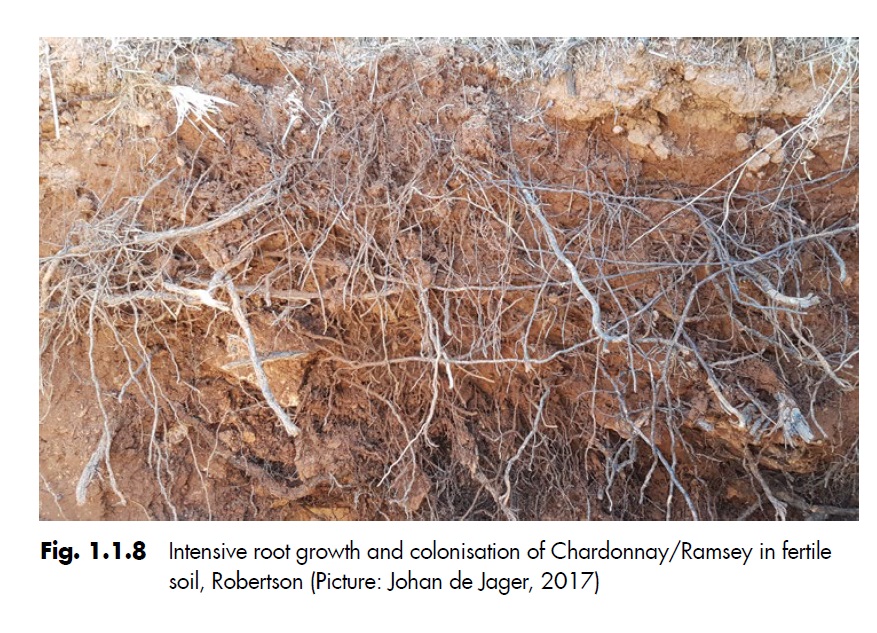

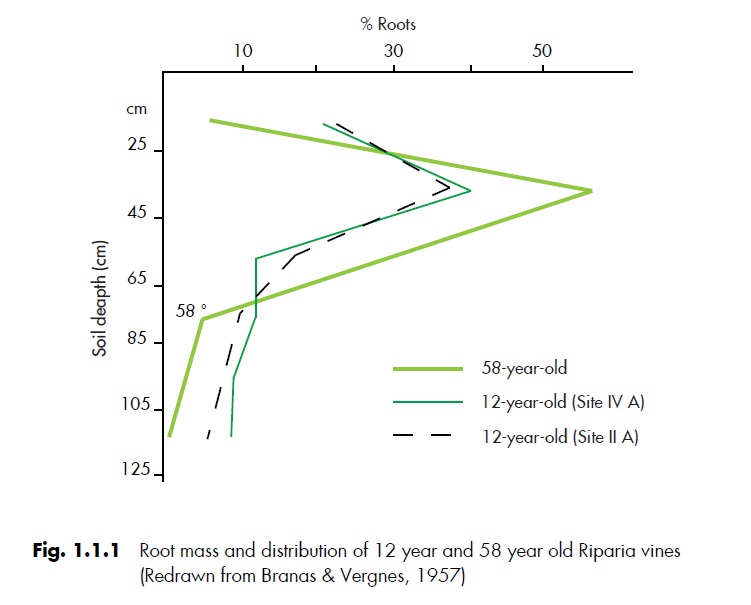

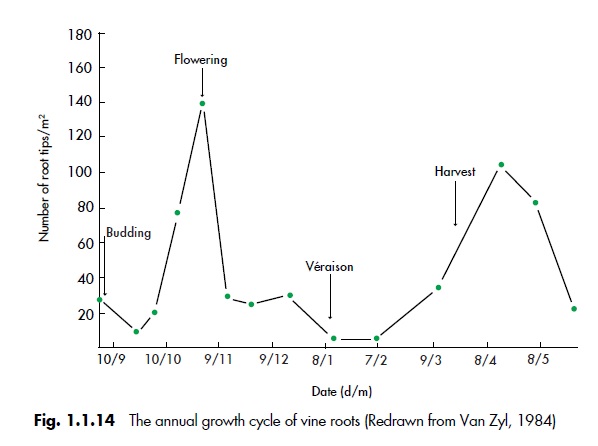

A much more interesting element to understand the balance of the vine (and therefore of the wine), but which is much less talked about, is the depth of the soil, i.e. how much space does the vine really have in order to develop a performing root system (see here and here on the roots). However, it is a very complex topic. The roots will necessarily develop little In a thin soil, which is certainly a limitation in less rainy climates. In areas where there is good water availability, however, it may be of little importance for water, although it can be a limitation for the mineral nutrition. The winemaker must understand that he must intervene more with fertilization. Furthermore, the climate-soil rapport can vary the actual availability of space. For example, a clayey soil in a very arid area can be problematic for the vine, because it becomes hard as a stone for most of the year, effectively reducing the growth capacity of the roots.

In conclusion, I have given several (non-exhaustive) examples of how there is a lot of variability in viticulture compared to certain stereotypes and prejudices, taking the example of Bolgheri Denomination. I therefore hope it is clear that, if a territory is suited to viticulture, the production choices can also be very different. There are no rules that are good everywhere. Instead, there are right or wrong choices for each particular condition. Furthermore, I hope I have clarified that the differences between soils and microclimates are not necessarily indicative of different quality levels, rather of different agricultural needs and different characteristics found in wines or, sometimes, of a better predisposition for certain varieties or types of wines.

Every winery that produces territorial wines knows that the inimitable identity of their products lies in the peculiarities of the vineyards. Only the right choices can enhance them in the wines.

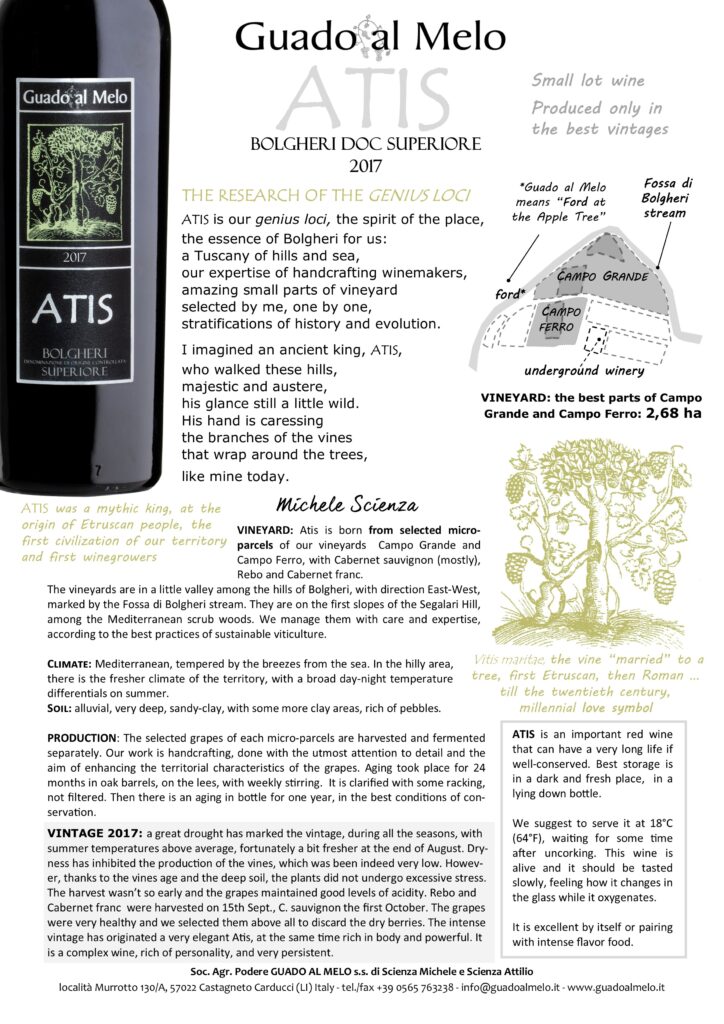

Atis 2018, new release: 95 p.ts by AIS

The AIS Sommelier Toscana magazine came out with an article presenting the new Bolgheri Superiore wines where Atis is among the best tastes, with 95 points.

2018 is the new release for us, because we have made the choice (since the origins of this wine, back in 2003) to let it mature for a longer time than the choices of other companies in the area which, as you can see, are releasing now the 2019. These are winery choices: in our opinion, Atis is a great wine that deserves more evolution and complexity, which it can receive from 2 years of aging in old wood on the lees and 1 year in the bottle. It is not filtered, but cleaned from the dregs only by decanting. We therefore propose it to you perfectly ready to enjoy, with the ability to evolve for decades.

2018 was a cooler than average vintage. Among other things, the second part of September was characterized by a significant drop in the temperatures (from about 30° to 20°C), thanks to the north-east wind. The ripening of the grapes at milder temperatures than usual, in a situation of sun and wind, has determined unique notes in this extraordinary wine.

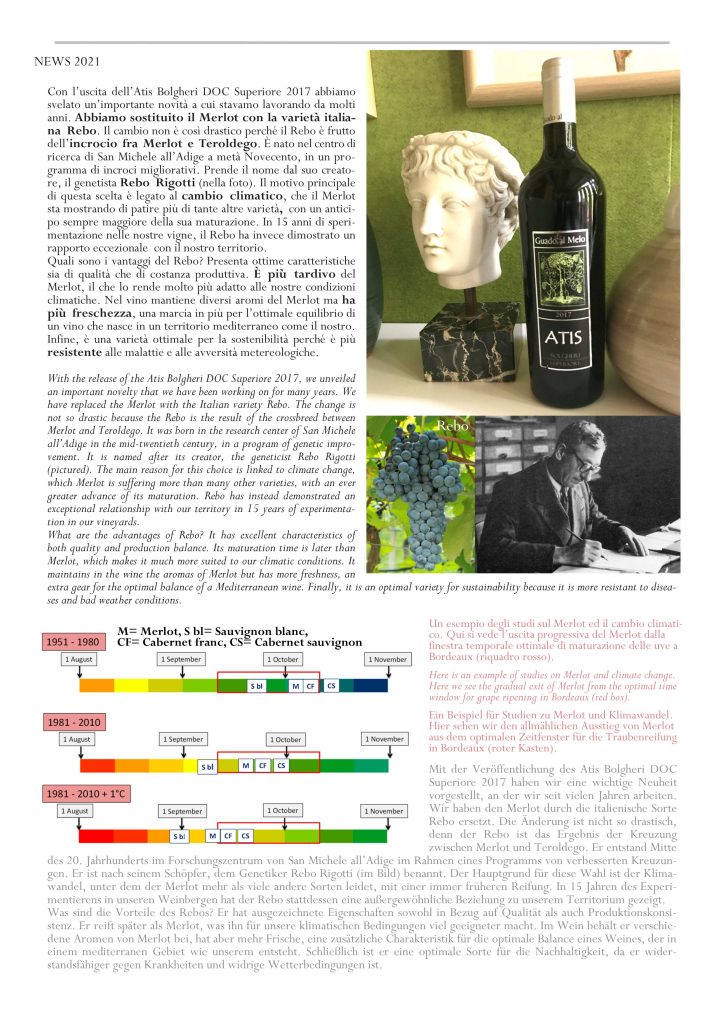

Another peculiarity of this special vintage concerns the grapes. Do you remember that we replaced 10% of Merlot with Rebo (read here) for the 2017 vintage? With 2018 we have increased even more this resistant variety, very interesting and perfectly adapted to our territory, reaching 15%, to the detriment of Cabernet franc, which has dropped to 5%. The main base, 80%, remains the great king of our vines, Cabernet Sauvignon, present here for over 100 years.

NB Unfortunately, these images are a preview of the magazine of not excellent quality. If you want to read the texts better, connect to this link, p. 38-39 (in Italian).

Stem or not stem vinification?

Have you ever heard of winemaking with grape stalks? Conversely, have you ever wondered why the destemming is the prevalent practice in the cellars? However, the “stem or not stem” diatribe is most likely as old as wine (or nearly so).

The grapes are usually destemmed and then pressed before the vinification. In fact, we speak of destemmer-crushing machines (be careful not to invert the sequence!). The stem vinification, on the other hand, consists in the vinification of the whole bunch, without destemming. The buch is lightly or not at all pressed. Another system provides that the grapes are first de-stemmed and crushed, then some stalks are added to the fermentation tanks. What is the best choice? Or rather, what are the advantages and disadvantages of these two practices?

Inevitably, by soaking in the must/wine, the stalks interact with it. They can release substances they contain or, conversely, absorb others. What is the stem composition? Try sucking on a piece and you will easily taste that it is tannic, slightly acidic and has a herbaceous aroma. The stalk contains water and various substances including some organic acids (tartaric and, above all, racemic), many tannins, etc. The acid component decreases with the lignification (it occurs in the last part of their seasonal cycle).

In wine history, both cases of winemaking can be found. Often, the choice was the result of chance, of the local tradition, or a consequence of the pressing techniques used. However, there was already a reflection on which system was better. In fact, if we read the viticultural treatises of all eras, from the Roman author Columella to the present day, the most common opinion was that vinification without stalks was better for obtaining fine and elegant wines, due to the bitter and herbaceous tastes brought from the stems. The stem fermentation was instead considered useful for wines from young vineyards or to improve those that were poor, in any case for wines with lower quality claims. We will see the reason for these statements. Today, we also have the data of numerous scientific researches that have compared winemaking with stems to that without.

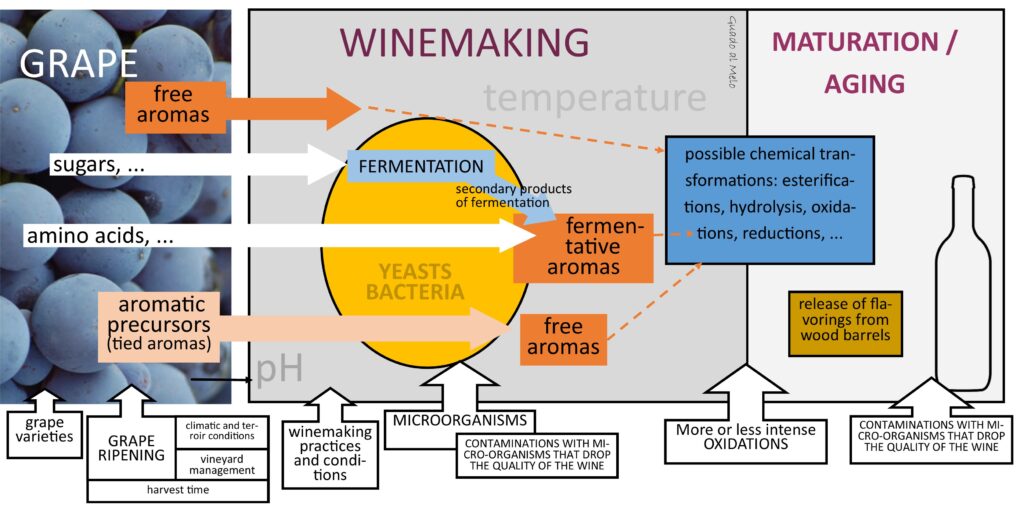

So, let's try to understand what are the general advantages and disadvantages of vinification with stems compared to that without. Here is a brief summary of the state of the art. Let's start with the secondary effects, to get to the most important ones. The analytical data that I report are taken from the article by M. Blackford et al., "A Review on Stems Composition and Their Impact on Wine Quality". , Molecules. 2021 Mar; 26 (5): 1240.

Does it improve the fermentation?

A first positive effect often mentioned in stem vinification is that there is a better fermentation. From the tests carried out, it is in fact possible to verify a slightly more favorable general trend. It is thought that this effect may be due to the additional amount of yeast that the stalks carry on their surface, as well as the ability to trap an amount of air between their roughnesses which favors the vitality of the microorganisms. Furthermore, the mass of the stalks seems to limit a little the temperature changes during fermentation, which favors the survival of the fermenting yeasts.

However, it has been found that the increased presence of oxygen also favors the development of unfavorable microorganisms. The most consequence is that there is generally a higher volatile acidity. Furthermore, in the presence of grapes that are not quite perfect, with some mold, the stem vinification seems to accentuate the severity of the effects on the wine, the so-called oxidase alteration (but it is not clear why).

The diluting and adsorbing effect

The stalks can release water in the must/wine, with a diluting effect on the other components. The water released is actually minimal on the mass of the must. Whether it is for this or for other reasons, in the research carried out there are differences in the composition of the must/wine, some minimal and others more important. Let's see which ones.

In stem vinification compared to that without, a slight increase in pH was measured (it varies from 1% to 9% in the studies) and a decrease in acidity (2% -15%), but not always confirmed in all studies and for all varieties. The variation in acidity could depend on the dilution but not only. It is thought that there is also an action on the phenomena that induce the precipitation of tartaric acid. In fact, the stalks increase the presence of salts (especially potassium, but also calcium and phosphorus), which bind to the tartrate and favor its precipitation. In some studies, there were also slight variations in other acids.

It is often said that stem vinification has the effect of lowering the alcohol content of the wine (today considered positive). There are those who have correlated it to the dilution, but also to a possible adsorption effect of the ethanol molecules by the structure of the stalk. However, this effect has not been seen in the studies: in some cases, the variation is zero, in others slight (it varies from 1% to 8%). I think it makes much more sense to work well in the vineyard to have adequate production balances.

The stalks, on the other hand, seem to have an effect on the decrease in the color of the red wine, more or less evident depending on the variety. Anthocyanins decrease from 1% to 22%, as does the intensity of color (from 7% to 33%). In particular, the yellowish reflections are accentuated in aging. The hypotheses about the cause are different, perhaps all together: dilution, color adsorption and pH variations.

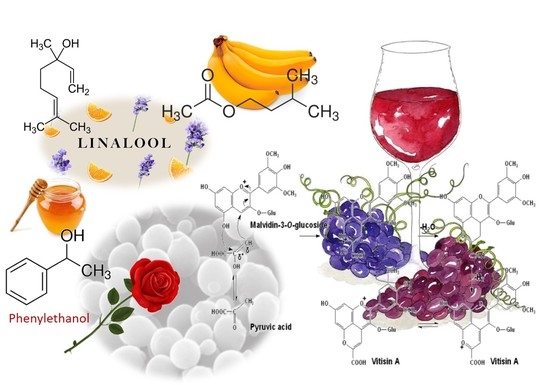

The most important effects: aromas and tannins

The stalks release aromas that are not exactly the most pleasant ones. Chemical analyzes confirm the increase above all of pyrazine compounds, which give "green" (grass or pepper) aromas. Aroma studies are not easy. As I wrote previously, even if we analyze the presence and concentration of the aromatic molecules in a complex solution such as wine, it is not easy to predict their olfactory perception. Studies of sensory analysis showed that the wines made with stalks are less fruity (fresh fruit), while the sensations of cooked fruit (jam), grass and spices increase. Somebody speaks of greater complexity, but the doubt remains about pleasantness, which is still a very personal element.

The effect on the taste of the wine, on the other hand, seems to be more defined. The researches have shown that stem vinification increases the sensation of astringency and bitterness in the wines. In fact, we finally arrive at the most important event in the winemaking with stems: the release of a great number of total polyphenols, in particular of tannins. The release of tannins is not always the same but still important, from 20% to 80%, depending on the grape variety, temperature and duration of the maceration. The incidence of tannins from the stalk is inverse to the duration of maceration: the longer it is, the more the tannins of the skins become predominant. If the maceration is short, however, the tannins of the stalk become (logically) the most important in the wine. We have therefore come to understand the main reason why it was considered useful in the past, in some cases, the vinification with stalks: the release of tannins in red wines.

The grape tannins are found mainly in the grape skin and are released into the must/wine during the skin maceration. Sometimes, however, the tannin is lacking, because poor quality grapes are used (for different reasons: because they are grown in unsuitable places, badly cultivated, for unfavorable vintages, harvests done at the wrong time, etc.), or because that variety is naturally poor of them. Historically, since the Roman times, systems have always been sought to add tannins to wines that do not have enough of them. However, since the ancient times, it was also understood that vegetable tannins are very different. Using one type rather than the other leads to a significant final difference in the taste of the wine. In the stalk, there are mainly tannins of a certain chemical type (catechinic) similar to those of the grape seeds and all the other green parts of the plant. Compared to the "noble" ones present in the grape skin, they are rougher in the mouth, much more herbaceous and bitter. Furthermore, they have a much stronger oxidative tendency.

In the past (since the Roman times), the tannin considered the best to add to wine was that from the oak galls. If you walk near these trees, you can easily see strange growths on different parts of the plant (branches, stem, etc.). The gall is formed following the attack of a parasite that causes an uncontrolled proliferation of cell tissues. The plant reacts by accumulating defense substances, the tannins, in that point. The use of gall tannins is very ancient and continues today, although purified products are now used which can also have very high costs. Instead, the stalks were considered another system to add tannins, but with low quality results. Sometimes the leaves were also added in vinification, with decidedly less elegant effects in the wine. These systems were however tolerated and recommended in the past for the great mass of low quality cheap wine.

But, do we really need to add tannin to wine today? That is the fundamental question! In an artisan production as our, thanks to today's knowledge, in a suitable area to the winegrowing, it is not necessary to correct the wines. It needs only when the grapes are the result of a bad work in the vineyard and in the cellar. In our opinion, the addition of tannin, whatever its origin, is something foreign to the production of a terroir-expressive wine. I don't think there is conceptually much difference if it is done with stalks or with a purified oak tannin.

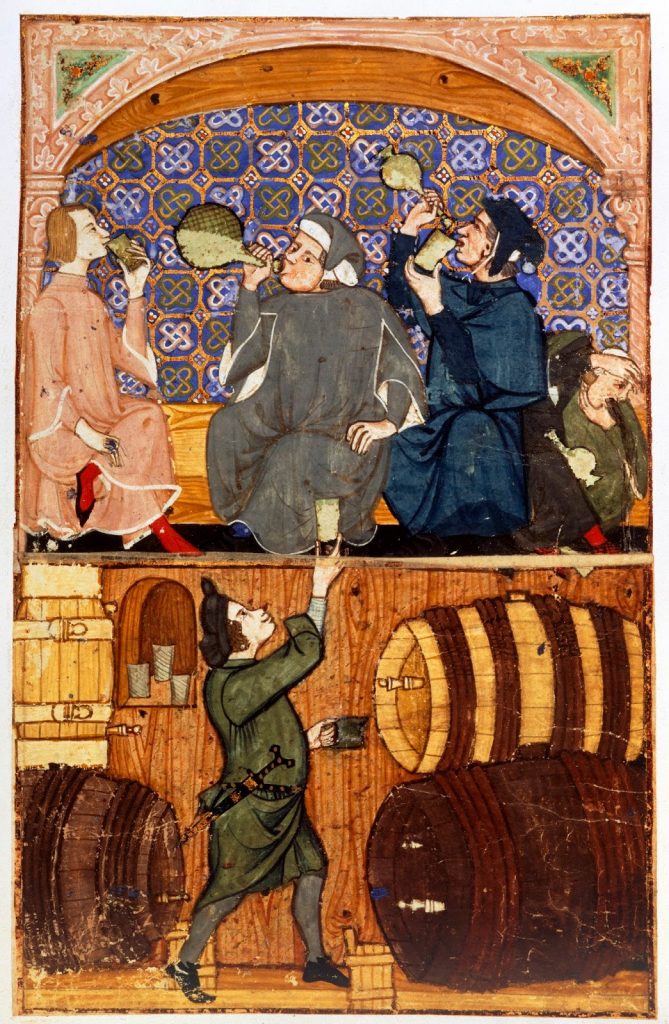

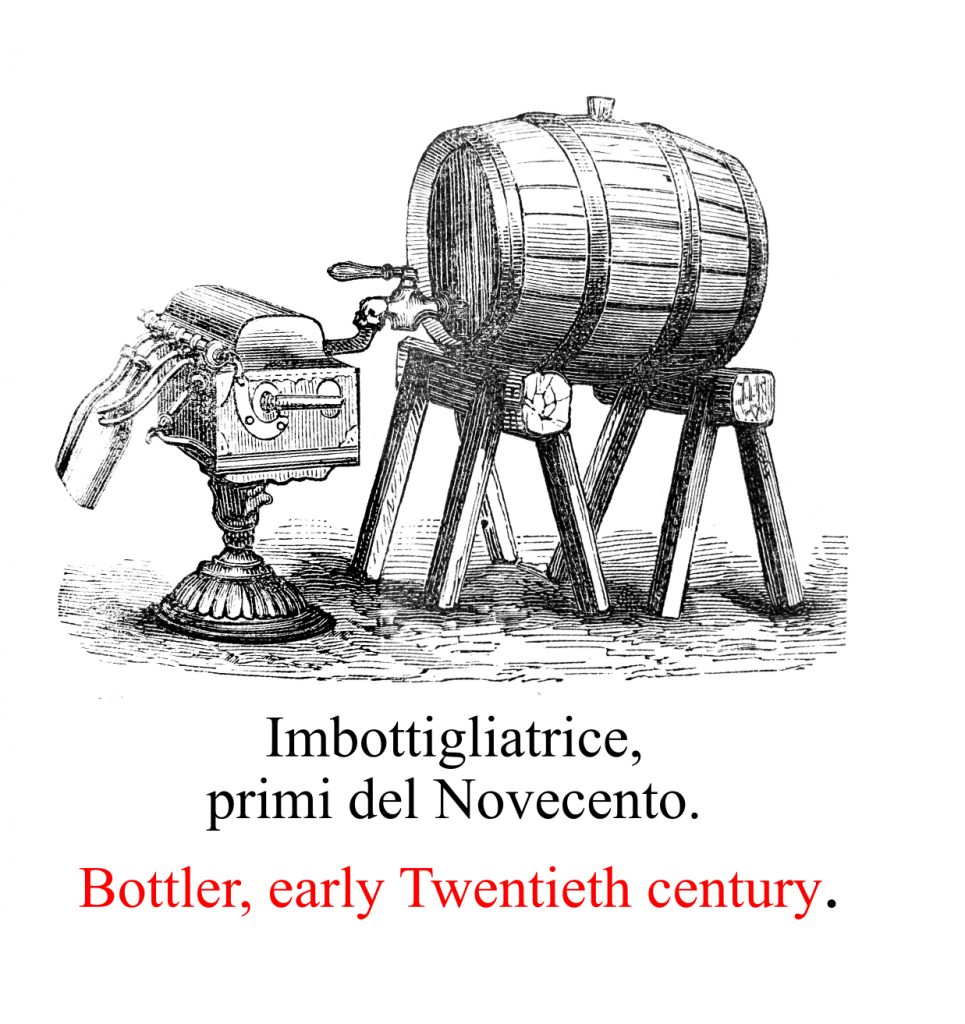

In the winery: from the hand destemming to the destemming machines

With the evolution of the winemaker practices of the nineteenth century, not only the stalks were rejected in fermentation, but even in the grape-pressing phase. The destemming became a qualitative practice described in all the viticulture texts, but carried out in the (few) wineries that produced refined wines. Later, it became more and more common.

A very crude ancient system for destemming, ancestor (at least in the concept) of the modern machines, was to rotate a branched stick in a basket of grapes. In the most advanced companies, a more laborious but delicate system was preferred, that is to remove the berries from the stem by hand. For obvious reasons, these expensive practices were reserved for the few high-value wines.

The first mechanical machines, first only crushers, then also destemmer-crushers, were for a long time viewed with suspicion due to the too destructive action on the grapes. The ones we use today are the result of a remarkable evolution which, over time, has leaded more and more towards the ability to act in a delicate way, carefully detaching the berries from the stalk without tearing or shredding the pedicels and the other green parts. Today's machines also have the ability to press the berries very little.

In the production of white wines, where the taste is much more delicate and the wine alters much more easily, it is yet more important not to bring bitter and astringent tastes unnecessarily in the must/wine, as well as easily oxidizable tannins. Many artisan winemakers, like us, do not press the whole bunches, but first they practice the destemming. After that, to be absolutely sure to eliminate all the small pieces of leaves or stalks or other, the cleaning of the must is carried out by spontaneous sedimentation. The must is stored overnight in the cool of the cellar and the sediments go down naturally to the bottom of the tank. Then, we remove the must from the above of the tank, without moving the sediment, and it was transferred to a new container for the fermentation.

Ultimately, I think you have understood that Michele and I do not vinify with stems and the reason. For us, a natural wine is made with grapes only, with its unique balances that are born in suitable vineyards, thanks to a very good work for each individual plant. We don't want to add nothing. The stalks bring something foreign to the fruit, not even so pleasant, which we prefer not to have. Our great territory already gives so much to our wines naturally, both in terms of taste and aromas. This does not mean that other winemakers could think that the contribution of stalks is useful, giving more importance to the advantages rather than the disadvantages.

The stalks are however important in our farm cycle, they are not just waste: after destemming, we put them in our composting area, where they contribute to form a perfect vegetable compost for fertilizing our vineyards.

Bibligraphy:

Riberaux-Gayon et al. “Trattato di scienza e tecnica enologica”, ed. AEB Brescia, 1980.

M. Blackford et al., “A Review on Stems Composition and Their Impact on Wine Quality”, Molecules. 2021 Mar; 26(5): 1240.

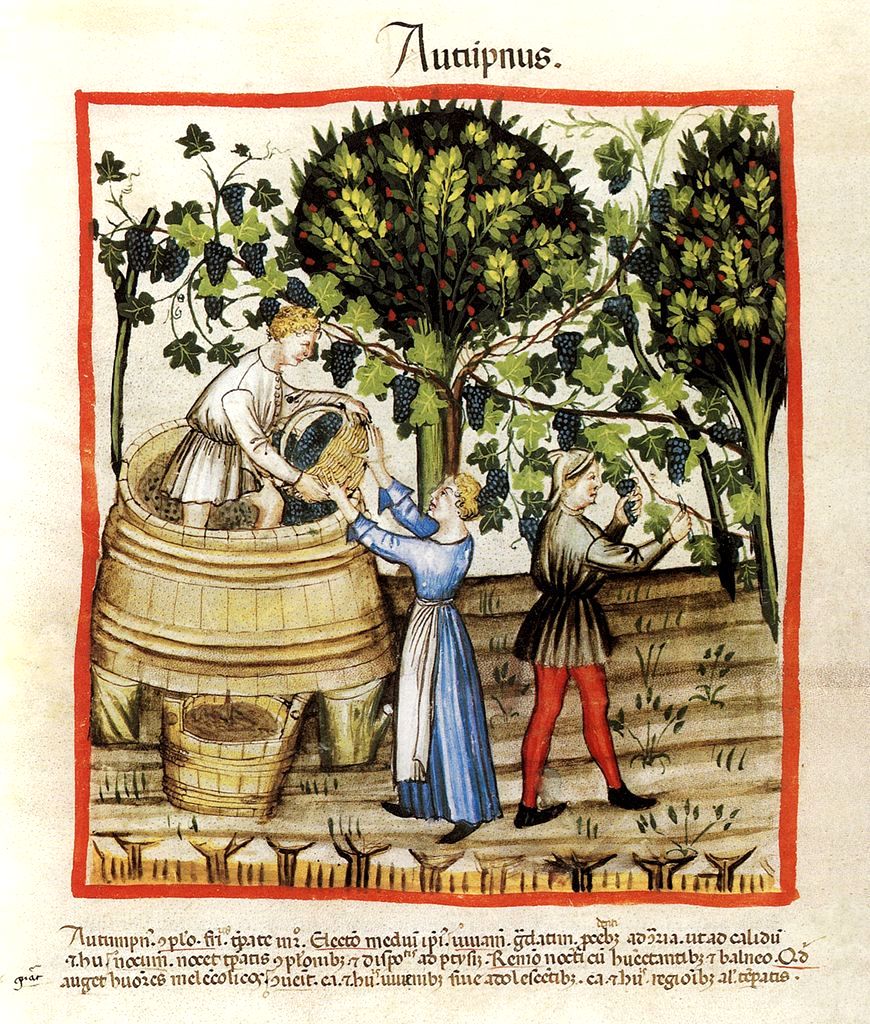

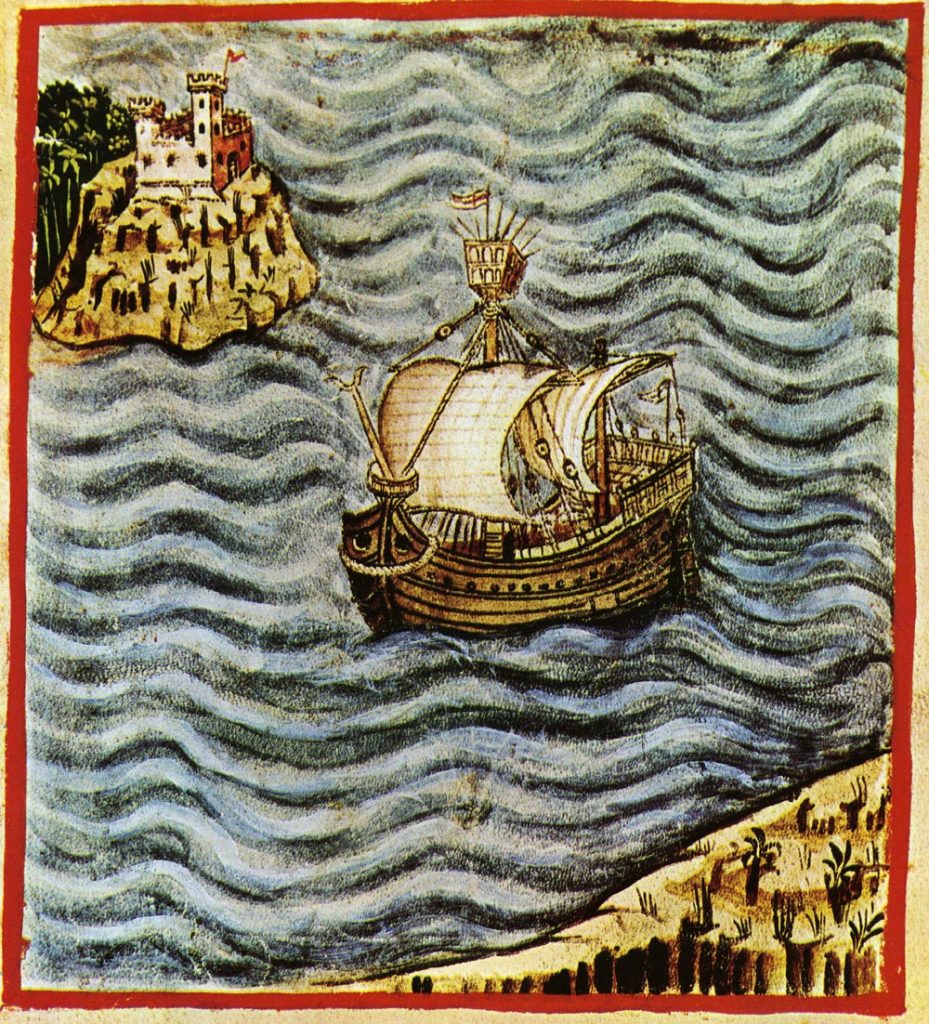

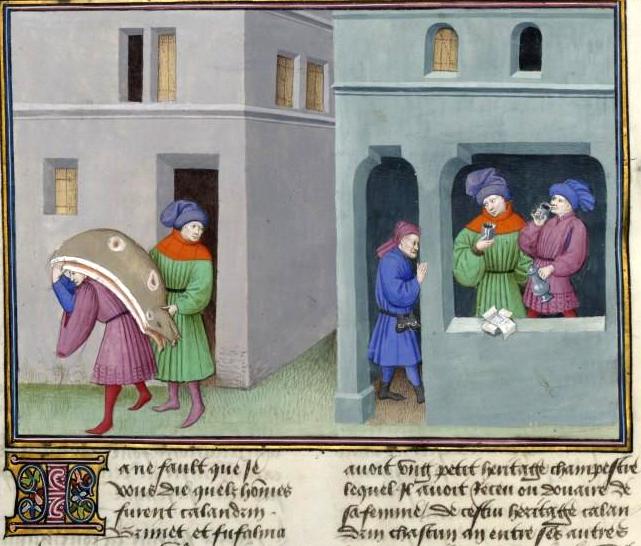

The vintage illustrations are from old books of our library on wine.

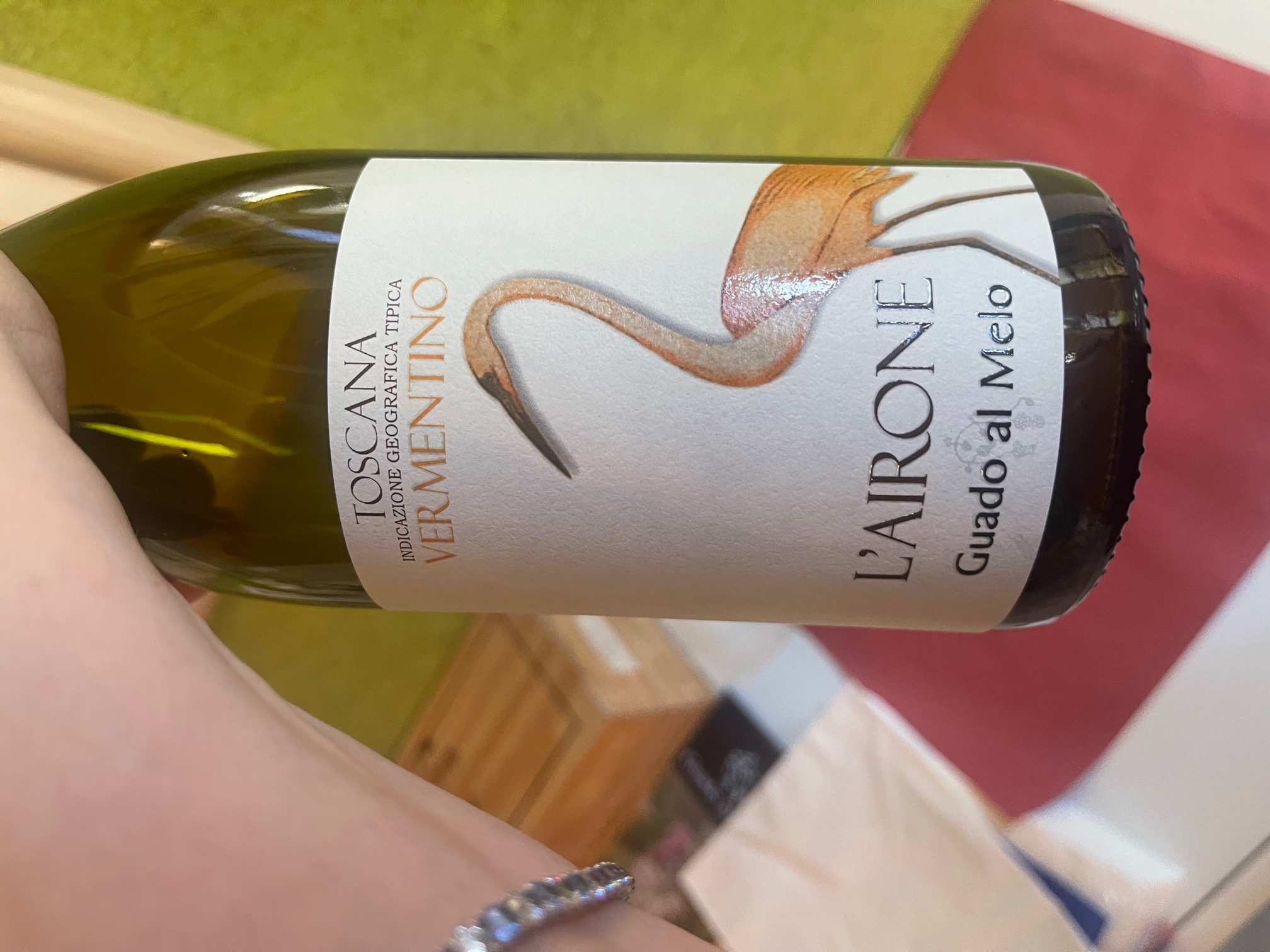

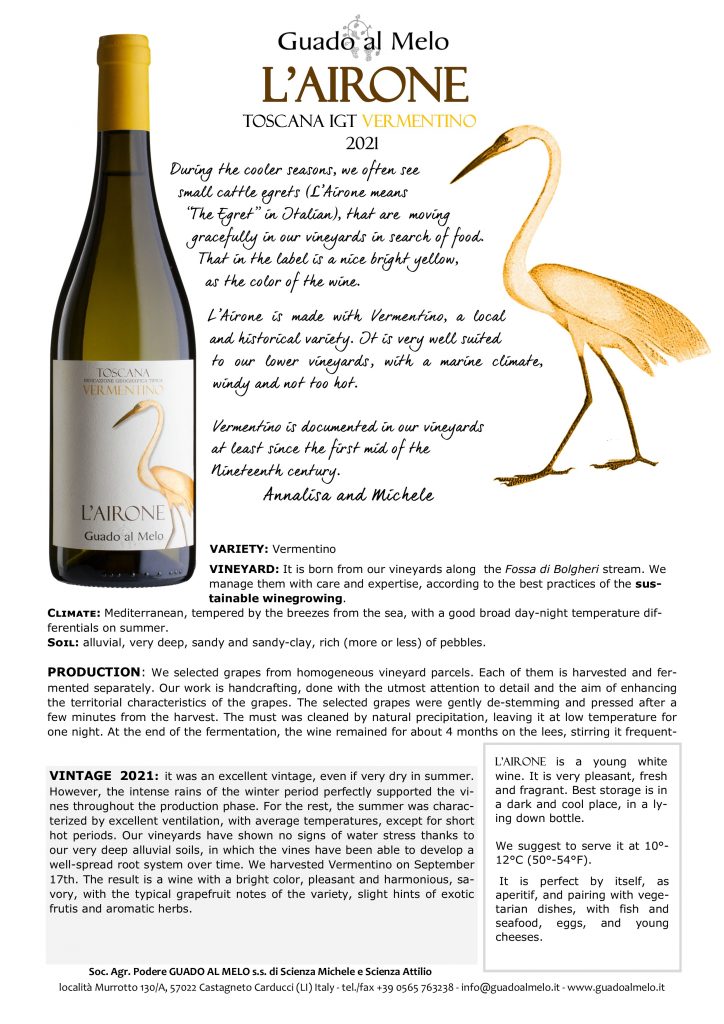

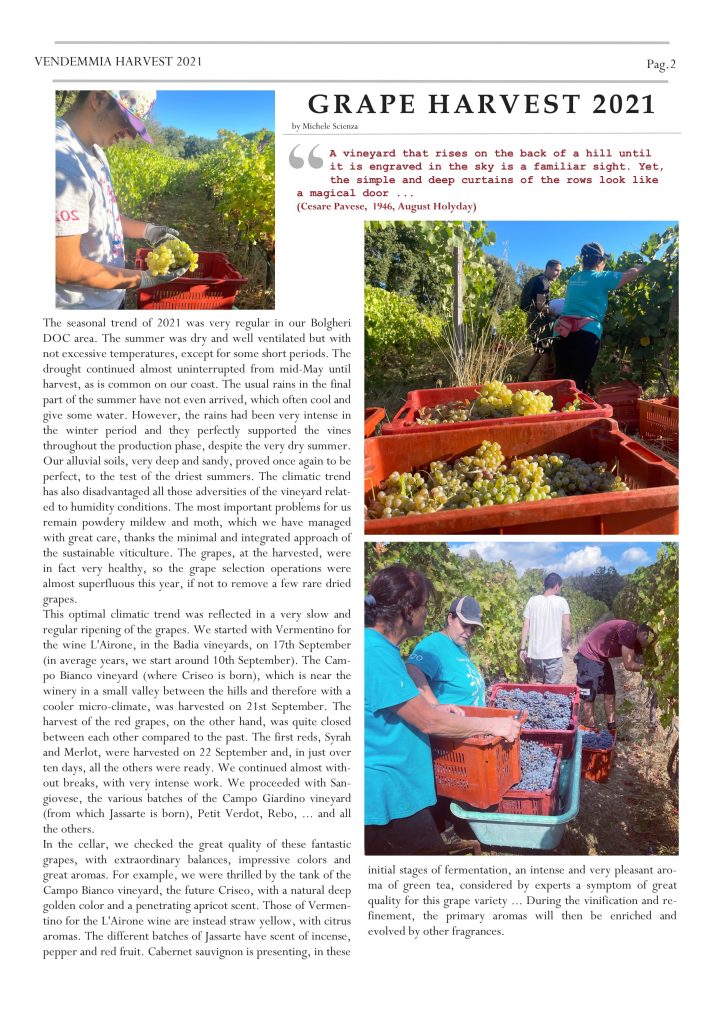

L'Airone 2021 is ready

We welcome the new vintage of the L'Airone which opens, as every year, our new releases. L'Airone is our white that expresses all the freshness of Vermentino, a perfect variety for our marine climate, which tolerates perfectly the wind and the heat of a mild Mediterranean climate like ours. This variety has been present on the Tuscan coast and, in general, the Tyrrhenian ones, for centuries, even if its origin is uncertain.

I have already talked at length about the last harvest: we judged it to be an excellent vintage. The summer was dry but our vines showed no symptoms of water suffering, because instead it had rained abundantly in winter. The temperatures were warm but without excess and the climate was been very well ventilated. The grapes were fabulous, perfect and healthy.

As usual, it has excellent aromas. In this juvenile phase, they are reminiscent above all of the typical citrus fruits of Vermentino, in particular the grapefruit, with delicate aromas of sage. It has also slight hints of exotic fruit, such as pineapple and passion fruit. In the mouth, it is very fresh and pleasantly light, with a fair length. However, an artisanal wine is alive and it will evolve over the months in the bottle . You'll can feel some aromas increase, such as those of exotic fruit, add others such as white flowers, light hints of honey and bread crust, …

It is an excellent wine to drink cool, I would say around 10°-12°C. As soon as it is taken out of the fridge (4°C), it will have few aromas. Remember: wait a while before drinking it, so it to warm up slightly and you'll enjoy all its aromatic complexity. Moreover, wait still a few minutes after uncorking, to oxygenate it well.

It is perfect as an aperitif but also to accompany dishes that are not too intense. For example, I can suggest you to drink it with classic spaghetti with clams, fried fish orfried vegetables, an omelette with aromatic herbs, a spring vegetable pie, …

If you don't drink it immediately, I recommend a good conservation! It is not really the best to keep a wine in the light (worse than ever under a spotlight!), at room temperature or in the heat. It's no a good idea to forget it in a refrigerator for months. All these situations mess it up, alter its aromas and taste, can cause precipitation of small crystals (nothing that hurts, it's just the natural potassium tartrate of the grapes). This happens because it is an artisanal wine: we do not do chemical stabilization or intense filtration, there is also the minimum possible sulfur dioxide. Store it with respect: the best is the bottle is lying down (standing up is possible only if you drink it shortly), in a cool place (about 10 °-12°C), in the dark.

Here there is the technical sheet of the wine, here the PDF.

Between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance: the dawn of a new Italian viticultural geography

During the fourteenth century, another oriental luxury wine was established. Its name was Malvasia, marketed by the Venetians. It seems that the name derives from the place where it was stored, Monembasia, a port in the Peloponnese, while the production seems to have taken place mainly in Crete Island. Malvasia was even stronger, fortified and sweet wine than the previous ones (it is thought between 16 and 18 % alcohol). It became the noblest wine of the time in all of Europe. It was imitated everywhere in Italy. Hence born the legacy of the many current Italian varieties named Malvasia (black Malvasia, black from Basilicata, long black, white, long white, white from Candia, white from Basilicata, from Casorzo, Lipari, Sardinia, Schierano, Istriana , etc.). All they are not genetically related to each other. They owe their name, most likely, to the fact that they were used locally in the past to produce the same type of wine.

As written in the previous post, almost all Italian wines up to the thirteenth century were anonymous and distinguished only by color (white= album, red = vermilium, ...), by flavor (dulce = sweet, bruscum =acid, ...), from the area of production (vinum de plano = wine from level ground, vinum de monte = wine from the hills, ecc.). With the fourteenth century, more and more local quality wines emerged, even if they did not imitate the oriental wines. They were yet for a local consumption, at most regional. They weren't luxurious, but they were starting to have higher prices, within the reach of medium class people. They were also the most recommended in medical treatises, which often disdained those of luxury because they were too heavy and aromatic. These wines slowly began to have a name, which could be linked to the production area or other characteristics. Among these we remember the different Moscatello, produced in various areas of Italy, Piedmontese Nebbiolo and Arneis, Ligurian Razzese, Lombard Groppello, Lombard-Venetian Schiava, Garganigo and Marzemino from Veneto, Friulian Refosco, Chianti Tuscan, Lacrima and Fiano from Campania, the southern Gaglioppo, etc. Some were a sort of local cloning of luxury wines, such as Vernaccia of Cellatica (near Brescia), Vernaccia of San Gimignano, Ribolla from Imola, Greco from Corsica, Greco from Velletri, Malvasia and Vernaccia from Sardinia.

The dawn of the modern grape varieties. There is little point in looking for current wines and varieties in the Middle Ages, even if sometimes the same names are found. There are too many centuries and many probable transformations between. The Middle Ages, like the ancient times, were a period in which wines but also a lot of varieties traveled, for the Mediterranean and for Europe, with also the possibility of crossings with local grapevines. These exchanges are recounted, for example, in "Trecentonovelle" ("Three hundred stories") (1390) by Franco Sacchetti. He wrote that in Italy there was so much desire to produce great wines that the winemakers tried to grab the best grape varieties from all over, recovering the rooted cuttings directly or exploiting the network of contacts offered by the Church. For example, Sacchetti reports that the Florentine nobleman Vieri de' Bardi sent off from Portovenere to his estate in Antella (Bagno a Ripoli, near Florence) some cuttings of a variety with which the famous Vernaccia of Coniglia wine was produced.

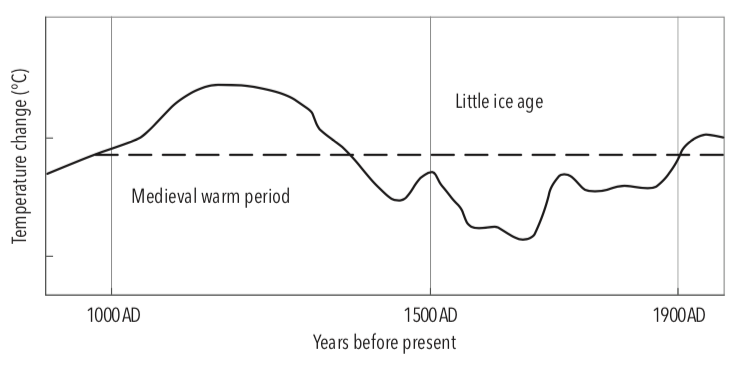

From the mid-1300s to the early 1400s, there were some important transformations which once again significantly changed the Italian wine geography.

On the one hand, the climate began to worsen more and more, after the medieval warm period that had favored the boom in viticulture. That cold period called the "Little Ice Age" began, which will shock all of Europe with a general agricultural crisis. The famines contributed to the spread of epidemics such as the Black Plague which, from 1348, led to the decimation of the populations. The crisis caused the decrease of agriculture in general, including the winegrowing. Furthermore, the cold made the grape vine disappear from all those territories where the climate had now become an insurmountable limit.

The wine between drunkenness, mockery and pleasure. The Black Plague is the background to Boccaccio's Decameron, about which I have told so far as the greatest medieval work that talks so much about wine. The Decameron is made up of a series of short stories that a group of young Florentine nobles, seven girls and three boys, tell in turn to pass the time in the country villa where they took refuge to escape the infection. In the introduction, Boccaccio describes the beauties of this residence, including the cellars, rich in fine wines, according to him more suitable for "good drinkers than for wise and honest women". In the Middle Ages, reputable women never must drink too much. However, at the times, the excess of wine was deplorable for everyone, both for the morals and for the health. But Boccaccio's stories are not very moralistic, often semi-serious. Drunkenness is linked to deception or teasing, while intelligent women often manage to cunningly overcome life's adversities.

The story of Alatiel. The beautiful Alatiel, daughter of the sultan of Babylon, is sent by her father in marriage to the king of Morocco. A long journey to the Mediterranean begins for her, during which she is kidnapped and violated by several men. The first, Pericone, thinks of making her give in with the wine. "Since he realized that she liked wine, which she was not used to because her religion prevented her from drinking it, he thought of making her surrender with the help of wine and Venus. One evening, he invited her to a party and ordered the cupbearer to serve her a glass of various wines mixed together. Having drunk the mixture, the woman, forgetting past misfortunes, became happy and seeing some women dancing Spanish dances, she too danced in the Alexandrian manner. So, she spent most of the night between wines and dances. When the guests left, the man, who was very robust and energetic, went into the room with the woman. She, warmer with wine than honesty, undressed and went to bed. " At the end of the story, Alatiel manages to return home. At that time, all these misadventures would compromise the life of a girl. However, she manages to convince her father that she has been welcomed all that time in a convent and so she marries her fiancé.

The semi-serious history of Tofano and Ghita. The rich Tofano is very jealous of his wife, the beautiful Ghita. His torment prompts her to correspond to a young suitor. The woman starts frequently gets her husband drunk to meet her lover. One night, as she returns from a date, her husband locks her out of the house, to unmask her in front of the neighbors. The woman threatens craftily to commit suicide, telling him that they would later blame him. Then, thanks to the darkness that hide her actions, she throws a stone into the well. The worried man runs to watch. Ghita quickly enters the house and locks her husband out. Tofano starts screaming and swearing, waking up the neighborhood, while Ghita yells at everyone that her husband always gets drunk and spends the night in the taverns. Tofano's misconduct spreads and reaches also the ears of Ghita's relatives, who beat the man and take the woman away. Eventually, Tofano, realizing that everything had started from his mad jealousy, repents and convinces his wife to come back, leaving her free to do as she pleases, as long as discreetly.

Between the end of the 14th century and the beginning of the 15th century, there was also an epochal change in trade, called the "freight revolution". Until then, the wine trade was limited to the most expensive products, as well as durable, because the shipping costs were calculated essentially on the basis of the volume occupied by the goods on the ship. The wine barrels take up a lot of space. Proportionately, it was cheaper to transport gemstones. The freight revolution instead introduced the use of calculating the cost also taking into account the value of the goods. The wine trade benefited greatly and, consequently, it had a very important increase.

As mentioned, until then the vine was grown practically everywhere in Italy, to have wine available for the community and, except for luxury products, the consumption of common wines was essentially local. As transportation became cheaper, more wines began to travel. The trade was also facilitated by the birth of larger political entities, which lowered the number of duties in travel and therefore the final price to the consumer. Furthermore, in the richer areas of Northern and Central Italy, there was also an improvement of the roads. So, people started to have a wide choice at their disposal. More and more, the consumption was focused on the best wines, not necessarily the local ones.

All these events contributed to once again change the Italian geography of wine. Viticulture decreased in general and, in particular, decreased or disappeared from all those areas where it is little or no suitable. On the contrary, it grew more and more in those districts considered of higher quality, where the economic performance became more and more relevant, such as Tuscany, the "Oltrepò Pavese", the Venetian hills, Istria, the Castelli Romani area, Apulia, Calabria, Langhe, etc. The high alcohol content of oriental wines (or made in that style), obtained by drying or concentration style, was not more necessary. It was enough if a good alcohol content, derived from an area suited to viticulture, for the wines to be preserved well enough, saving their pleasantness and aromas.

As marketing increased, the need for wines to be recognizable, with precise identities, increased more and more. Till then, they spoke only of red or white wine or a little more. From now, the names of the wines began to become a common practice. They often derived from the type of product, often combined with the place of production or, in other cases, that of storage or distribution, rarely of the grape varieties. Particularly suited areas began to be mentioned more and more, sometimes even the single high-quality vineyards. For example, 106 different wine producing locations near the city are identified in the Florentine land registry of 1427.

But don't think that there was a great clarity, like today. The situation was still very confused, both for the time and for modern scholars who tried to decipher it, because with the same name and origin there are also wines with very different characteristics (white and red, sweet and non-sweet wines, etc.). We are still a long way from a very precise and defined geography of wine. We can say that it was starting to take shape.

In the fifteenth century the consumption of wine was by now very advanced. The wines began to be distinguished and known for their organoleptic and cultural peculiarities, as well as for their combinations with food. The first cookery treaties were also born in that period.

In the mid-fifteenth century, the Byzantine Empire collapsed, Genoese trade with the eastern Mediterranean disappeared, while the Venetian one was considerably reduced. The prestige of oriental or oriental-style wines (very sweet, flavored and alcoholic) collapsed. However, their taste was not completely lost, especially in the banquets and the ceremonies. However, a new type of luxury wine was imposed, the one coming from a suitable territory, dry, not excessively alcoholic, white or red, pleasantly scented. They were young wines, as the aging processes will only be "discovered" again a few centuries later. However, we will talk more about the Renaissance another time.

... To be continued

Bibliography:

Prof. Alfonso Marini (AA 2020-2021) Dispense del corso di storia medievale.

Pini, Antonio Ivan (2003) Il vino del ricco e il vino del povero. In: La civiltà del vino. Fonti, temi e produzioni vitivinicole dal Medioevo al Novecento. Atti del convegno (Monticelli Brusati, Antica Fratta, 5-6 ottobre 2001). Centro culturale artistico di Franciacorta e del Sebino, Brescia, pp. 585-598.

Antonio Saltini (1998), Per la storia delle pratiche di cantina (parte 1) enologia antica, enologia moderna: un solo vino, o bevande incomparabili? In Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura n.1, giugno 1998.

Branca Paolo (2003) Il vino nella cultura arabo-musulmana. Un genere letterario… e qualcosa di più. In: La civiltà del vino. Fonti, temi e produzioni vitivinicole dal Medioevo al Novecento. Atti del convegno (Monticelli Brusati, Antica Fratta, 5-6 ottobre 2001). Centro culturale artistico di Franciacorta e del Sebino, Brescia, pp. 165-191.

Anna Maria Grasso, Girolamo Fiorentino (2012) Archeologia e storia della vite e del vino nel medioevo italiano. Il contributo dell’archeobotanica e di nuove metodologie di analisi integrate per la caratterizzazione varietale applicate ai contesti archeologici della Puglia meridionale. 2012, VI Congresso Nazionale di Archeologia Medievale

AAVV (1988) Il vino nell’economia e nella Società italiana medioevale e moderna. Convegno di Studi Greve in Chianti, 21-24 maggio 1987 Firenze, in Quaderni della Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura, Accademia dei Georgofili Firenze.

Emilio Sereni (1961), Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano, Editori Laterza.

Pietro Stara (2013), Il discorso del vino - origine, identità, come problemi storico-sociali, ed. Zero in Condotta.

Giovanni Spani (2010-2011), Il vino di Boccaccio: Usi e abusi in alcune novelle del Decameron, Heliotropia 8-9.

Gino Tellini (2014), Il "figlio del sole" : vino e letteratura in Toscana. Soc. Ed. Fiorentina

Between the Early and Late Middle Ages: overseas, Latin and Greek wines

“Vinum de vite dat nobis gaudia vite. /Si duo sunt vina, mihi de miliore propina. / Non prosunt vina, nisi fiat repetitio trina. / Dum quartum poto, succedunt gaudia voto. / Ad potum quintum mens vadit in laberintum. / Sexta potatio me cogi abite suppinum.” (Salimbene de Adam, XIII sec.)

“The wine of the vine gives us the joys of life. If there are two qualities of wine, give me the best. We do not enjoy wines if we do not repeat the drink three times. At the fourth, desire is followed by delights. On the fifth drink, the mind enters a labyrinth. The sixth drink makes me fall on my back. " From the chronicles of Salimbene de Adam (13th century)

Between the end of the Early and the start of the Late Middle Ages, the greater political stability and the favorable climate led to notable progress in agriculture. The vineyards, in particular, expanded and spread more and more. The notable increase in production made wine go back to being the drink of the people in Italy, as it had already been in Roman times. It was different in other European countries. Where production was more difficult or wine was an imported drink, it remained for a long time only the prerogative of the rich.

The wine went from sign of prestige or a liturgical necessity to an economic activity. After the year 1000, the bourgeois agricultural property also spread, in particular from the 12th century. The wine production was the symbol of social ascent for the bourgeois. The increase in production will increasingly lead to its commercialization, marking the success over time of those territories that were located in places that facilitated its transport, such as the coastal areas and along the navigable rivers of Europe. Let's go to discover how.

The viticulture spread very much In Italy. Each territory, even the least suitable, dedicated an important part of its agricultural land to the vine. The remarkable documentation we have of the period, especially between the 13th and 14th centuries, shows us an incredible spread of vines everywhere, both in the peripheral areas and in the centers of cities and villages. At the time, the local wines were anonymous, defined only by the color, the organoleptic characteristics, and the alcohol content. They were consumed essentially locally.

The increase in wine production became a concern of the legislator. In the municipal statutes there were many provisions related to the cultivation and management of the vineyards, at the date of the harvest, the transport, the retail and wholesale of grapes and wine, at the duties and the tariffs. In general, the regulations tended to push towards a production of quantities, capable of providing enough wine for the consumption of the community. Furthermore, the statutes were aimed at favoring the consumption of local wines and making it difficult for foreigners to enter (vina forensia).

In the thirteenth century, however, the poet Cecco Angiolieri wrote that he was tired of the local (Latin) wine and wanted to drink something different::

"... and all I want is Greek and Vernaccia wines, / because Latin wine bores me, ...".

In fact, the great availability of local wine pushed more and more the rich and powerful Italians to seek distinction in luxury products, represented at the time by the exotic wines of the eastern Mediterranean, which arrived together with spices, silk, jewels and the relics of the saints. Their prestige lay in the high price.

The wines traveled a lot from the thirteenth century onwards, throughout the Mediterranean, to and from Italy, passing through the three great trading posts of the time: Genoa, Pisa and Venice. The wine traveled in small barrels, by sea or river, on ships or barges. Upon departure (or arrival), the barrels were transferred to ox-drawn carts or to the burden of the mules. The above maritime republics dominated these trades for a long time, throughout the Mediterranean and towards the northern Europe.

The oriental wines were called in the documents of the time "ultramarine" (today we would say overseas) or "navigated". They reached the final consumer at considerable cost, both for the long journey and for the numerous duties that were charged there. The Oriental wines, often generically also referred to as "wines of Romania", came from the Byzantine Empire. In this generic group, several more specific origins will be distinguished later, such as the wine of Crete, Chios, Lesbos, Tire (now in Lebanon), ... At the time, these were the few wines that endured very long journeys, thanks to the high alcohol content. They were white wines, sweet and fortified, concentrated by cooking the must or drying the grapes, enriched with spices, perfumes and honey. These exotic wines, whose purchase possibility was a status symbol of wealth and prestige, conquered the rich of the time for over three centuries, from the thirteenth to the fifteenth century. Their trade became a monopoly of the Venetians after the capture of Constantinople in 1204. During the 13th century, this trade increased more and more, thanks to the expansion of the possible buyers, no longer only nobles and ecclesiastics, but also the new rich bourgeois.

Genoa tried to counter the monopoly of Venice with the trade of local and southern wines, produced in the style of the wines of Romania. They were Ligurian Vernaccia and wines from southern Italy, coming from those areas that had remained for centuries under the Byzantine rule: Calabria and part of Campania. For the latters, the term "Greek" wine was born, which at the time was equivalent to "Byzantine", as opposed to the so-called "Latin" wine, produced in the rest of Italy, but above all with very different characteristics. From Calabria, the Greek wines arrived in Naples. Here, they were taken over by Genoese and Pisan merchants, who market them throughout the western Mediterranean, in Northern Italy and the rest of Europe. The term "Greek" was then also used not only to indicate the real geographical origin, but for all the wines made with the same characteristics. This term has remained as legacy in the names of several current Italian wines and grape varieties.

Then, other Italian wines began to be among the most expensive. The wine Ribolla, also marketed by the Venetians, was perhaps originally from Friuli or Istria. It was a sweet and strong white wine, but less than the oriental ones. Trebbiano was a dry white wine, probably of Tuscan origin, widespread in many other regions. Furthermore, Vernaccia began to be produced also in Tuscany. As in the previous cases, in fact, the names of these wines were born from geographical links but then became indicative of a type of wine. At the time, they could therefore be produced in different territories, with the local varieties. Trebbiano and Vernaccia were mainly marketed by the Genoese and Pisans, then also by the Florentines.

Vernaccia, wine par excellence in The Decameron. Vernaccia was among the first wines to take a name in the Italian Middle Ages, thanks to the Genoese who managed to give it the status of luxury wine, capable of competing with the wines of Romania. The success then brought production out of the Ligurian borders, especially in Tuscany and Sardinia. This wine was praised by poets, such as Folgore from San Gimignano in the 13th century, and in the novellas (short stories) of Boccaccio or Sercambi of the 14th century. Above all, it is Boccaccio who frequently mentions it in the Decameron. In the short story "Calandrino and the heliotrope", Vernaccia is the symbol of pure enjoyment. Maso tells of the Land of Bengodi ("Great Enjoying") where the vineyards are tied with the sausages and the mountains are made of grated Parmesan cheese. There, it is possible to drink Vernaccia all day, which also flows in the rivers: "and nearby ran a river of Vernaccia, the best you ever drank, without any drop of water in it". In the short story "Calandrino and the stolen pig", Vernaccia takes on a magical value. Bruno and Buffalmacco, who enjoy making fun of the naive Calandrino, try to convince him to pretend the theft of his pig, to deceive his wife and enjoy the money. Because his refusal, they steal the pig secretly and accuse Calandrino of having implemented the plan on his own. At this point, they push him to organize a sort of "ordeal", those tests of the most ancient Middle Ages in the balance between religion and magic, to demonstrate who was the author of the theft. They make him believe that they are able to prepare enchanted ginger biscuits, served with Vernaccia, which will be indigestible for the culprit of the theft. All the inhabitants of the village are invited to the test, who are served biscuits and wine. The two pranksters manage to give only Calandrino some biscuits made very bitter by the addition of aloe, blatantly demonstrating his guilt. The final joke is that the poor man is also forced to give them two capons, so that they do not tell anything about what happened to his wife. In another short story, Vernaccia also demonstrates healing abilities. In fact, the brigand-gentleman Ghino di Tacco cures the terrible stomach ache of the abbot of Clignì with a diet based on toast, broad beans and Vernaccia ("Ghino di Tacco and the abbot of Clignì").

To be continued ...

Bibliography:

Prof. Alfonso Marini (AA 2020-2021) Dispense del corso di storia medievale.

Pini, Antonio Ivan (2003) Il vino del ricco e il vino del povero. In: La civiltà del vino. Fonti, temi e produzioni vitivinicole dal Medioevo al Novecento. Atti del convegno (Monticelli Brusati, Antica Fratta, 5-6 ottobre 2001). Centro culturale artistico di Franciacorta e del Sebino, Brescia, pp. 585-598.

Antonio Saltini (1998), Per la storia delle pratiche di cantina (parte 1) enologia antica, enologia moderna: un solo vino, o bevande incomparabili? In Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura n.1, giugno 1998.

Anna Maria Grasso, Girolamo Fiorentino (2012) Archeologia e storia della vite e del vino nel medioevo italiano. Il contributo dell’archeobotanica e di nuove metodologie di analisi integrate per la caratterizzazione varietale applicate ai contesti archeologici della Puglia meridionale. 2012, VI Congresso Nazionale di Archeologia Medievale

AAVV (1988) Il vino nell’economia e nella Società italiana medioevale e moderna. Convegno di Studi Greve in Chianti, 21-24 maggio 1987 Firenze, in Quaderni della Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura, Accademia dei Georgofili Firenze.

Emilio Sereni (1961), Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano, Editori Laterza.

Pietro Stara (2013), Il discorso del vino - origine, identità, come problemi storico-sociali, ed. Zero in Condotta.

The wine in the Early Middle Ages: between pleasure and sacredness

Italy, called the Enotria by the ancient Greeks (= "land of wine"), continued to be its homeland even in the Middle Ages, but the transition from Roman times was certainly not easy (as I have already told here). Already from the end of the Roman Empire, there was a generalized political crisis, with wars and invasions, which was also reflected in the viticulture crisis. The cultivation of the vine requires high specialization, as well as constant and expensive care for almost the year, so it suffers more than many other crops in times of instability.

Gregory the Great wrote in the 6th century that in Italy “eversae urbes, castra eruta … nullus terram nostram cultor inhabitat”: “the cities are destroyed, the castles demolished, … the lands deserted by farmers”. The production of wine therefore dropped significantly, albeit in a different way in different European areas.

In general, the reduction in production made the wine a product almost exclusively of the rich and powerful, as in very ancient times. The mass of the people partly turned to poorer alcoholic products, obtained by fermenting the available fruits, such as apple, fig, carnelian, rowan, blackberry, medlar, etc. As mentioned in the previous post, the refined Roman production techniques, both viticultural and enological, were lost, as well as knowledge in many other fields. In the Middle Ages something then re-emerged, as evidenced by the agrarian treatise by Pietro de' Crescenzo from Bologna (1304). Most of this knowledge will be regained more later.

The Christian religion played a great role in this complicated transition. The wine was used in religious rites since ancient times but in Christianity it assumed an importance as perhaps never before. The Mass took shape precisely in this period and in the Eucharistic rite the act of Jesus Christ of the Last Supper was repeated ("This is my body, this is my blood"). The Middle Ages was a period very rich in symbolism: the bread was also a symbol of active life, the wine symbolized contemplative life, that is, the ability to know the essence of things, a virtue that God has granted only to human beings among all his creatures. In any case, wine became a fundamental raw material for mass and its production was therefore indispensable for every church and every convent. The production of Mass wine was tried everywhere, even where the climatic conditions were prohibitive or otherwise difficult.

The miraculous wine. The wine also played a very important role in the many miracles attributed to medieval saints. It is wrotten in the book "Tractatus de miraculis S. Francisci" (Treatise on the miracles of St. Francis) by Tommaso da Celano (1247-1257): "When he was at the hermitage of St. Urbain, the blessed Francis was gravely sick; he asked for some wine with dry lips, they told him there was none. He then asked some water and, when they brought it to him, he blessed it with a sign of the cross. Immediately, the water lost its flavor, and took another. What before was pure water became excellent wine, and what poverty could not, sanctity provided. After drinking it, that man of God recovered very quickly and as the miraculous conversion of water into wine was the cause of the healing, so the miraculous healing testified to that conversion.”

The gravestone of a 9th-century abbot from Milan reads: "Templa, domos, vites, oleas, pomeria struxit", that is, "he built palaces and houses, planted vines, olive trees and fruit trees". The monastic orders and bishops dealt abundantly with viticulture, not only for liturgical purposes, but also to have this drink as a sign of hospitality towards illustrious guests (or not). Around the year one thousand, the invasions and wars eased and civilized life began to regroup. The vineyards also extended to the nascent new political order, made up of princes and lords, by imitation of the Church, by prestige and to honor the guests.

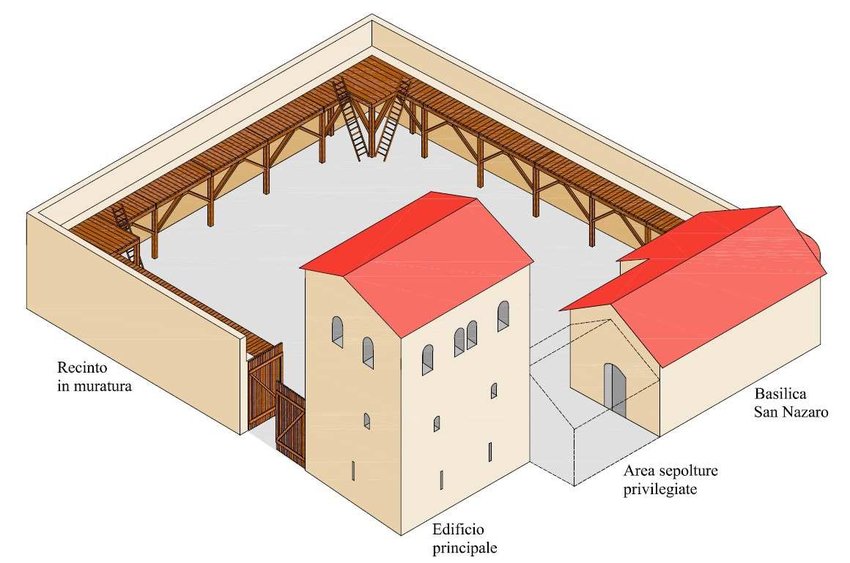

The reorganization of the countryside often restarted from the ancient Roman villae, where the invader, the new lord, settled. In Lombard and Byzantine times, the old villa, which has now become a fortified farmhouse (castrum), was the center of the new territorial lordship, called curtes or domuscultae or massae, ... depending on the different areas of Italy. It was the place of residence of the lord or of his local administrator or of the ecclesiastical power. The castrum formed the pars dominica (the part of the lord), together with a church and directly managed agricultural areas, worked by non-free servants. They included cultivated fields, pastures, specialized crops such as vineyards or orchards, as well as particular resources such as mills, ponds, etc. The second element of the curtis was constituted by the pars massaricia, that is the farms cultivated by dependent peasants, required to pay taxes and work also in the pars dominica. We speak of the feudal system, very similar to that of Late Roman Empire (see here)

Another religion, Islam, which was born in this period (7th century AD), instead led to the disappearance of wine production in all those Mediterranean countries that came under its influence. It seems that only a small production made for pharmaceutical purposes but also for clandestine consumption, more or less tolerated by the authorities, survived. Moreover, the Christian and Jewish communities often maintained the possibility of producing wine in derogation, with payment of a tax. A particular case seems to be represented by Sicily, whose Arab invasion began in 827 and lasted until the beginning of the Norman conquest, in 1061. A recent research has revealed that the production of wine in the Arab Sicily not only continued but that it even increased, compared to the previous period. It is not known if the Sicilian Arabs produced or drank wine. Almost certainly, the numerous Christian communities that stubbornly opposed Islamization did it. However, it has been ascertained that there was a significant trade in Sicilian wine in the Mediterranean during the period of Arab domination.

However, in general, in the early Middle Ages a new geography of wine was born, defined more or less by the borders of Christianity, with a center of gravity a little more shifted from the Mediterranean towards the heart of Europe.

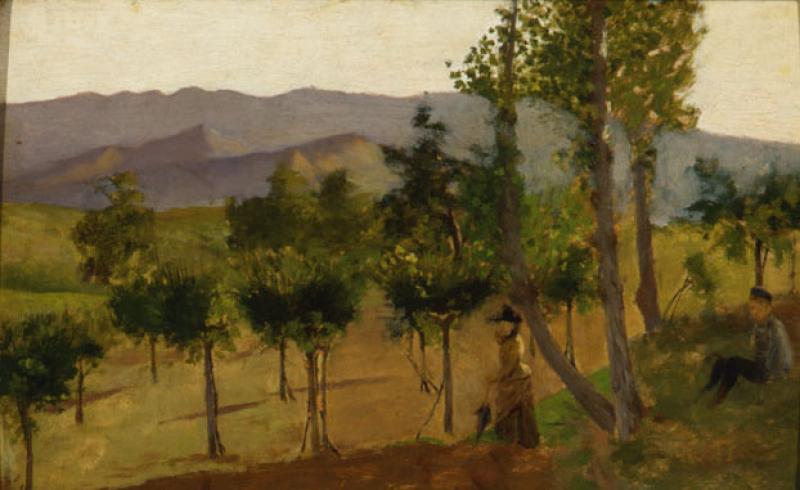

The center of agricultural knowledge was the Arab world int he Early Middle Ages, as in many other fields. Among the many treatises on agriculture, the one considered to be the most important was written by Ibn al-Awwam in the 12th century ("Book of Agriculture"). He was able to merge the legacy of the knowledge of the Romans, especially of Columella, with those of his time. However, he does not speak of wine, given the Koranic prohibition of alcoholic beverages. He only mentions the cultivation of grapes, for fresh and dried consumption. The cultivation is described in the two usual forms that we have already learned about, spread throughout the Mediterranean by the Romans: the low vine, cultivated as sapling without support, sometimes in holes or with poles, and the high one, often "married" to other fruit trees or pergolas.

If these indications are valid in general, there are also important differences between the Italian world of wine and that of more central and northern Europe. Where the climatic conditions were more difficult, the production of wine was more expensive and complicated, so for centuries viticulture remained almost the exclusive prerogative of ecclesiastics or lords. On the other hand, thanks to our Mediterranean climate, the winegrowing remained notably widespread even in the peasant world, because it was much more spontaneous and easier to manage. For example, Grasso and Fiorentino (2012) examined the archaeo-botanical remains of vine seeds in 39 medieval archaeological sites throughout Italy, from the 6th to the 15th century. AD They found evidence in almost all of them, not only in monasteries but also in villages, even in the most ancient centuries.

The viticulture in Italy was certainly reduced but not as dramatically as elsewhere. We can also think of a patchy situation, where some areas suffered more and others instead had more continuity with the past. For example, in the sixth century AD, Cassiodorus, minister of the Gothic king Theodoric, testifies in a letter to the quality of the wines produced by the peasants of the hills near Verona, in particular the acinaticum wine, a passito wine which he describes as follows: "A very rich set on the royal tables is praised as an ornament of the State [...] and, therefore, the wines that the fertile Italy produces in a singular way must be procured ... This is a very pleasant wine, regal in the color, singular in the flavor. [...] Its sweetness is felt with ineffable delicacy; its concentration receives vigor from I don't know what force; its density is incredible, so that you would say it is a fleshy liquid or a drink to be eaten."

The "dead's thirst". The wine stood between pleasure and religion for the people of the Middle Ages, between earthly and afterlife. This conception is magnificently exemplified in the Facezia XXX of the "Mottos and Jokes" by the Priest Arlotto (1484). One day, at dawn, the priest is talking to an innkeeper at the Uccellatoio hill (near Florence), when a panting man approaches and asks him to offer him some wine: "For Goodness sake, pay me a half-pitcher because I am very thirsty". Surprisingly, the priest Arlotto recognizes the man as the famous humanist Leonardo Bruni from Arezzo, and is amazed by his anxiety and such an early hour. Bruni replies: "Don't you see that I am dead? I must walk away and I cannot stay with you. Don't you see my problem: I am so thirsty and I have no money to pay for a little wine?". Then, the priest asks him amazed what happened his wealth, his science, his illustrious fame ... In short, he argument about the transience of earthly goods. Bruni's answer is obviously that nothing remains after death, that it is wise to enjoy life in moderation and also do good. The story shows the dead as a very anguish man, disoriented in front of an unknown journey. He dwells on his life, he is afraid for the divine judgment that is coming. He is in a hurry, cold but he makes very thirsty at the same time. The meeting between the living and the dead man takes place at dawn, on a road on the top of a hill, in an ordinary but at the same time supernatural situation, rich in symbolism on the theme of transit. As the historian Franco Cardini tells us, the "dead's thirst" is a theme that has ancient roots in the Mediterranean area. In various civilizations, particularly those of arid areas, where the suffering of thirst is well known, it was believed that the dead had difficulty in leaving life and suffered from a sort of thirst, that is, the urge to move on, to die permanently, to return into the earth. They need the living to help them die, by quenching their thirst. The ancient Greeks poured water into the crevices of the tombs in the Hydrophoria feast. In the Anthesteria festival, it was believed that the first rains of spring quench the thirst of the dead. I also remember you the Gospel parable of the poor Lazarus and the rich man, who gives nothing to the beggar of the leftovers of his rich table. After death, Lazarus goes to heaven and the rich man burns in the hellfire. The damned invokes Abraham to send Lazarus to at least dip his finger in the water to relieve his terrible thirst. However, the water is more linked to baptism in Christianity. The last drink, in continuity with the classical world, is instead the last glass of wine of farewell from the friends, therefore also the last drink of the funeral wake (or banquet), as well as the comfort of the Eucharist. The priest Arlotto offers the dead man, tired and frightened, the warmth of charity and of the last glass of wine, which gives him the strength and courage for his difficult journey.

To be Continued ...

Bibliography:

Prof. Alfonso Marini (AA 2020-2021) Dispense del corso di storia medievale.

Pini, Antonio Ivan (2003) Il vino del ricco e il vino del povero. In: La civiltà del vino. Fonti, temi e produzioni vitivinicole dal Medioevo al Novecento. Atti del convegno (Monticelli Brusati, Antica Fratta, 5-6 ottobre 2001). Centro culturale artistico di Franciacorta e del Sebino, Brescia, pp. 585-598.

Antonio Saltini (1998), Per la storia delle pratiche di cantina (parte 1) enologia antica, enologia moderna: un solo vino, o bevande incomparabili? In Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura n.1, giugno 1998.

Branca Paolo (2003) Il vino nella cultura arabo-musulmana. Un genere letterario… e qualcosa di più. In: La civiltà del vino. Fonti, temi e produzioni vitivinicole dal Medioevo al Novecento. Atti del convegno (Monticelli Brusati, Antica Fratta, 5-6 ottobre 2001). Centro culturale artistico di Franciacorta e del Sebino, Brescia, pp. 165-191.

Anna Maria Grasso, Girolamo Fiorentino (2012) Archeologia e storia della vite e del vino nel medioevo italiano. Il contributo dell’archeobotanica e di nuove metodologie di analisi integrate per la caratterizzazione varietale applicate ai contesti archeologici della Puglia meridionale. 2012, VI Congresso Nazionale di Archeologia Medievale

AAVV (1988) Il vino nell’economia e nella Società italiana medioevale e moderna. Convegno di Studi Greve in Chianti, 21-24 maggio 1987 Firenze, in Quaderni della Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura, Accademia dei Georgofili Firenze.

Emilio Sereni (1961), Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano, Editori Laterza.

Pietro Stara (2013), Il discorso del vino - origine, identità, come problemi storico-sociali, ed. Zero in Condotta.